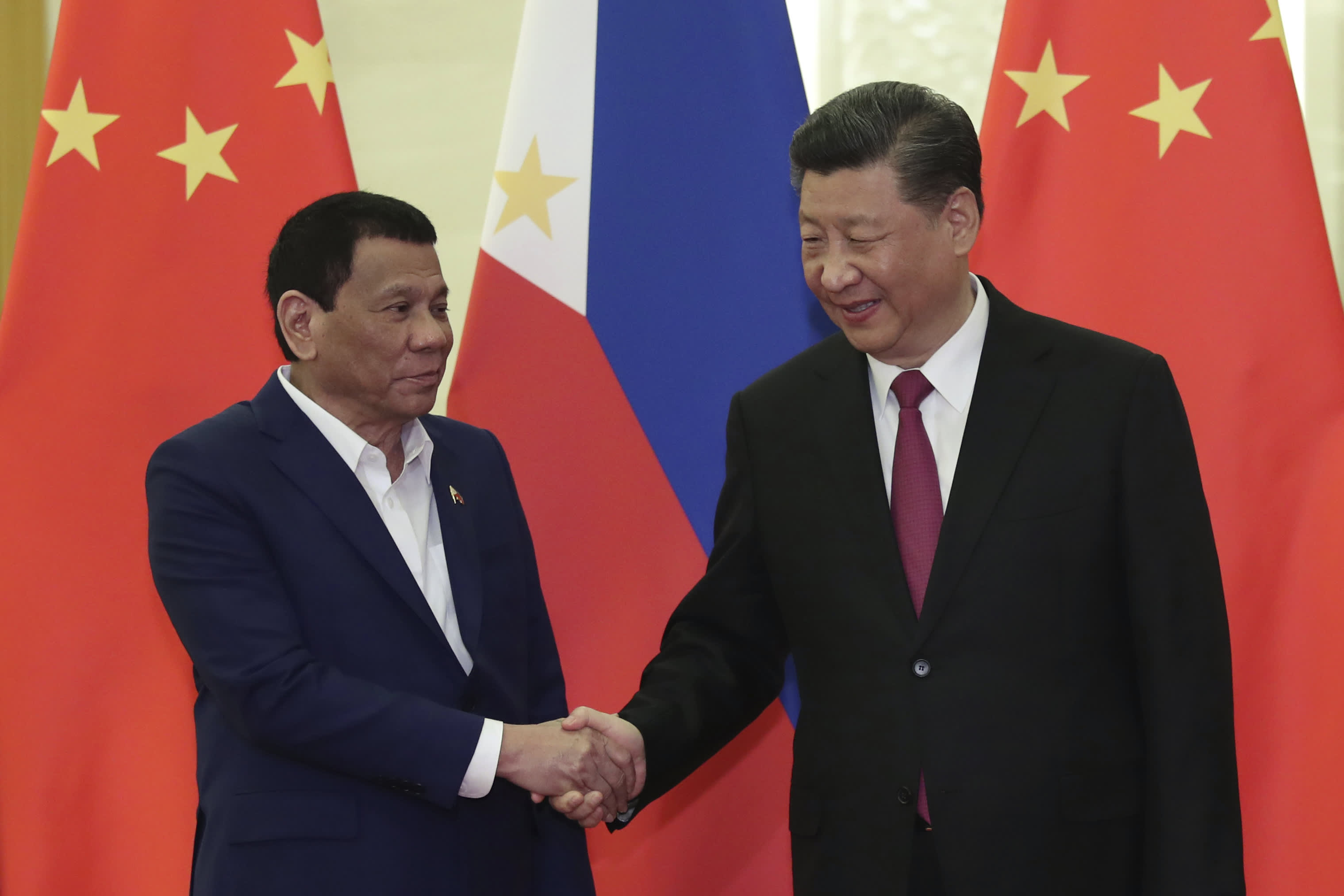

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte met with Chinese President Xi Jinping in April, 2019 in Beijing, China.

Kenzaburo Fukuhara | Kyodo News | Getty Images

SINGAPORE — After more than four years in power, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte is still struggling to show that his country has benefited from a closer alliance with China.

In a dramatic shift in the Philippines’ foreign policy, Duterte declared in 2016 the country’s “separation” from the U.S. — a military ally — and announced closer ties with China.

Among other things, the president also set aside his country’s territorial dispute with Beijing in the South China Sea, in exchange for billions of dollars that China pledged in infrastructure investments.

But much of those promised investments have not materialized and many of those projects were delayed or shelved, while anti-Chinese rhetoric has been growing louder within Duterte’s own government and among the Philippine public.

So on all counts, Duterte is increasingly accused of having abased himself before Beijing and gotten nothing for it.

Greg Poling

Center for Strategic and International Studies

“China has launched just two of the pledged infrastructure projects — a bridge and an irrigation project — and both have hit major snags that could scuttle them altogether,” said Greg Poling, senior fellow for Southeast Asia and director of Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“Beijing has also not backed off on harassing Filipino forces and civilians in the South China Sea. So on all counts, Duterte is increasingly accused of having abased himself before Beijing and gotten nothing for it,” Poling told CNBC in an email.

Rising domestic political pressure

Duterte’s conciliatory approach toward China is not shared by most of the Philippine public, who continue to view other global and regional powers more favorably.

In a July survey by pollster Social Weather Stations, Filipinos were found to trust the U.S. and Australia more than China. Notably, trust in China was worse than the same survey conducted in December last year.

Such deterioration in public sentiment against China coincided with the coronavirus pandemic — which ravaged the Philippine economy — and Beijing’s continued aggression in the South China Sea where the two countries have overlapping territorial claims.

All that “increased domestic political pressure on Duterte to recalibrate his pivot to China,” Peter Mumford, practice head for Southeast and South Asia at Eurasia Group, told CNBC via email.

The Philippines in recent months made several foreign policy moves against China that analysts said were noteworthy coming from the Duterte government:

The Philippines and China have for years clashed over competing claims in the resource-rich waterway where trillions of dollars of global trade pass through annually. The Southeast Asian country — under former President Benigno Aquino III — took China to court.

In 2016, shortly after Duterte took office, an international tribunal ruled that portions claimed by both countries belong to the Philippines alone.

China ignored the ruling, while critics said Duterte did little to demand compliance from Beijing. Even while China-skeptic voices within his administration grew, Duterte stayed largely silent, analysts noted.

Running out of time

As a whole, remarks critical of China from Duterte’s own cabinet “do not signal an imminent shift in the administration’s stance towards China,” said Dereck Aw, a senior analyst at Control Risks.

He explained to CNBC that those comments “should be viewed as deliberate attempts to placate domestic stakeholders, such as growing parts of military and the public, that are skeptical about Duterte’s China policy.”

“Ties between China and the Philippines will remain stable as long as Duterte is president,” he said, adding that Duterte may sometimes turn to “nationalistic rhetoric” to help his preferred successor in the 2022 presidential election.

“But actions speak louder than words: the Duterte administration will continue to deepen economic engagement with China and to refuse to internationalise the South China Sea dispute,” Aw said in an email.

But with less than two years left in his six-year term, Duterte is running out of time to get the economic results he had wanted from Beijing.

Eurasia Group’s Mumford noted that despite the largely unfulfilled Chinese promises, Duterte’s argument is that his country is still “better off” in avoiding aggression with China given the “asymmetry of power” between them.

“Nevertheless, Duterte is coming under increasing pressure to demonstrate the gains from relations with China,” he said.