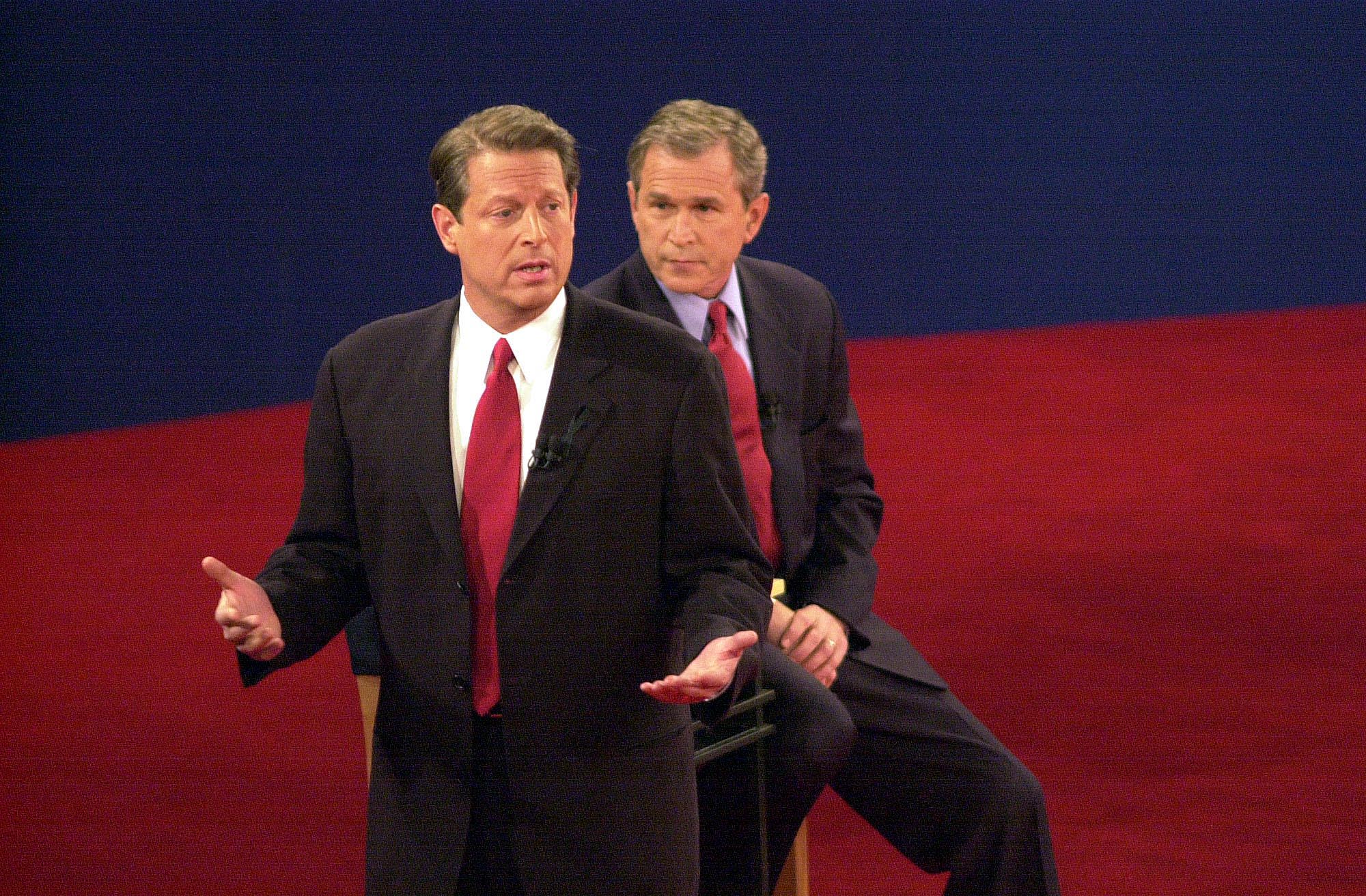

Democratic presidential candidate Vice President Al Gore talks to the audience while the Republican candidate Texas governor George W. Bush looks on October 17, 2000 in St. Louis, Missouri at the third and final presidential debate of the campaign.

Bill Greenblatt | Hulton Archive | Getty Images

In a normal election year, Bush v. Gore is the worst-case-scenario for those hoping for a smooth transition of American power.

Not 2020.

This year, an unusually fierce onslaught of litigation over the presidential contest between President Donald Trump and Democratic nominee Joe Biden has created the conditions for a battle that would dwarf the Supreme Court fight over hanging chads in Florida two decades ago, top elections experts warn.

A chief concern is that the legal drama on Election Day and in the days immediately after could play out simultaneously in multiple crucial states, leaving the ultimate outcome of the presidential race up in the air. That worry is compounded by the fact that more voters than ever are expected to vote by mail as a result of coronavirus, potentially delaying the release of results beyond election night.

“In the event that the election is effectively tied, and comes down to a few of these states with a large number of absentee ballots, then we have a version of Bush v. Gore on steroids,” said Nathaniel Persily, a democracy scholar at Stanford Law School and the co-founder of the Stanford-MIT Project on a Healthy Election.

A flood of legal battles that are already underway provides some insight into what’s to come.

Already, more than 300 Covid-19 related election suits have been filed across at least 44 states, according to a tracker maintained by the Stanford-MIT team. As was to be expected, the lawsuits are disproportionately taking place in states that are the most likely to matter in a close election, such as Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Michigan.

Persily said the 2020 election was already going to be litigious before the Covid-19 pandemic hit because of the high-stakes nature of the race, in which both sides view success or defeat as existentially important.

“Add on top of that the curve ball the pandemic throws into the electoral system, and you have a series of novel legal issues that need to be resolved before the election — and this is happening at a time that the electoral infrastructure is undergoing the most major renovation, in the shortest time, in years,” he said.

The suits follow familiar patterns. Democrats are pushing for expanded access to voting, particularly vote by mail. On the other side, the GOP has filed suits to make voting rules more restrictive, arguing that loosened rules could lead to voter fraud.

Some of the arguments advanced by Republican lawyers echo a baseless theory that the president has put forward, suggesting that voter fraud is rampant. Voter fraud is rare for any type of voting.

The legal battles are consuming a significant amount of time and resources.

On the Democratic side, Biden said over the summer that his campaign has assembled a team of 600 lawyers and 10,000 volunteers to fend off any election “chicanery.”

The Republican National Committee and the Trump campaign, meanwhile, have said they’ll spend $20 million on legal fights, doubling a previous pledge.

The RNC and Marc Elias, an outspoken Democratic elections lawyer, have produced maps showing the spread of election litigation in which they are involved in states around the country.

Representatives for the Trump and Biden campaigns did not respond to requests for comment.

Sylvia Albert, the director of voting and elections at the nonpartisan pro-democracy group Common Cause, said the tidal wave of early litigation suggests that Republicans and Democrats will have more potential targets for emergency lawsuits that could swing the race.

“Both parties will be looking at every state to see whether a lawsuit could help their candidate win,” Albert said. “I think there’s a likelihood of Florida times 10.”

Should any cases make their way to the Supreme Court, it’s not clear how the justices would rule — especially without knowing the precise nature of the dispute. In the few disputes related to voting and Covid-19 that the court has ruled on to date, it has delivered a mixed bag of outcomes.

In one illustration of the court’s unpredictability, last month it rejected an effort by Republicans opposing eased vote-by-mail rules in Rhode Island that were supported by state officials. The month before, it blocked a court ruling that would have imposed similar eased rules in Alabama.

In both cases, and in several other similar ones, the court has shown more of a reluctance to second-guess state officials than support for any particular voting rules.

The top court has a 5-4 majority of Republican appointed justices, including two of Trump’s nominees, Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh.

Paul Smith, an elections expert at Georgetown University Law Center and the vice president for litigation and strategy at the Campaign Legal Center, a nonpartisan good governance organization, said that much of the way the election unfolds could be determined by the vote margin.

“As the outcome gets more and more uncertain, if the decisive state is in fact too close to call, then it becomes more difficult,” Smith said. “If it is clear who won the election, then it is easier to see the way through.”

While it is unlikely that the outcome will be “absolutely clear” on election night, Smith’s “good scenario” is that enough states report results to allow observers to predict with some certainty who the winner is going to be.

That scenario could depend on Florida.

“Florida is likely to report its results on election night or shortly thereafter,” Smith said. “If Biden wins Florida, there really is no path for Trump to carry the rest of the electoral votes.”

— Data visualization by CNBC’s Nate Rattner