Months of failure to control the coronavirus pandemic’s destruction in the U.S. has resulted in historic levels of high unemployment. Roughly 27 million Americans are receiving jobless benefits, and nearly half of people out of work no longer expect to return to their previous jobs.

But, just like the virus’s outsize impact on the health of communities of color, the unemployment crisis is in a number of ways worse among Black Americans, who are disproportionately more likely to be unemployed but are also least likely to receive jobless benefits. Just 13% of Black people out of work from April to June received unemployment benefits, compared with 24% of White workers, 22% of Hispanic workers and 18% of workers of other races, according to an analysis completed by Nyanya Browne and William Spriggs of Howard University using national survey data from the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago.

Spriggs, who is also chief economist to the AFL-CIO, tells CNBC Make It the racial benefits gap has persisted over time but appears to be worse during the current economic downturn. After the 2008 financial crisis, for example, 24% of jobless Black workers received unemployment compared with 33% of jobless White workers, according to a 2012 study of national claims data by the Urban Institute.

Racial disparities in unemployment persist despite pandemic relief efforts

Racial discrimination in the labor market means Black workers are more likely to be terminated, more likely to have their unemployment claims denied by their employer, and more likely to receive less aid when they do get through, Spriggs says.

The racial gap in people receiving jobless aid persists despite sweeping enhancements to the unemployment system through the March CARES Act, which provided a weekly $600 federal boost through July, extended the unemployment benefit window by 13 weeks and made more workers eligible for aid through Pandemic Unemployment Assistance through the end of 2020.

“Part of the explanation has to do with some discrimination on the part of employers in slowing claims for Black workers,” Spriggs says, explaining that employers are more likely to dispute unemployment claims from former Black employees. While the Department of Labor says disputes must be resolved within two weeks, “when you look at data, it’s taking over half of claims more than five weeks to get resolved,” Spriggs says. “Black workers are being caught up in that process at a disproportionate rate.”

The unemployment system is designed to leave people out

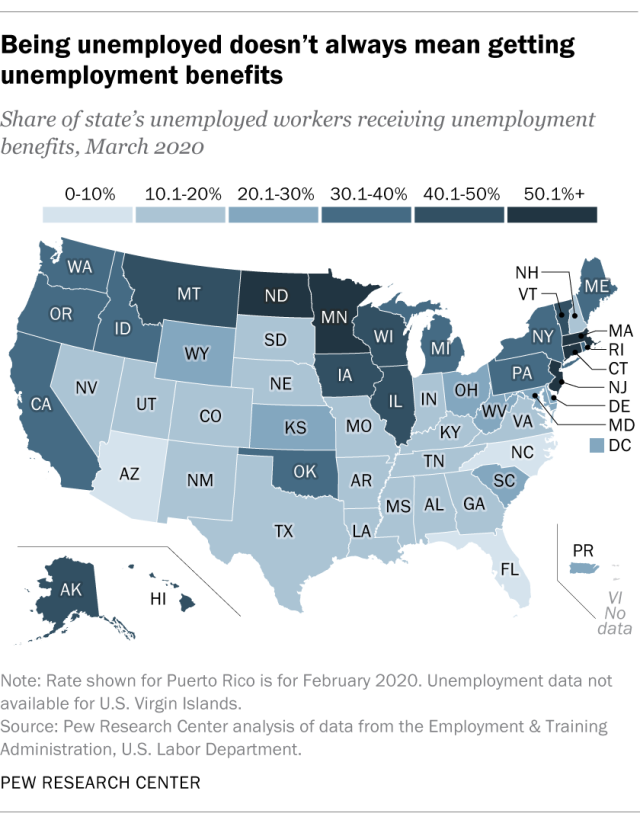

Because each state administers its own unemployment program, geography plays a major role in the benefits gap. “A disproportionate share of Blacks live in states that are least efficient in processing unemployment claims,” Spriggs says.

Over the years, Southern states with higher populations of Black residents have made some of the deepest cuts to unemployment funding, including in Florida and North Carolina where severely reduced staff and outdated technology deter many people from applying.

In March 2020, 29% of unemployed Americans nationwide received jobless benefits, according to Pew Research Center. But in Massachusetts, where 9% of residents are Black, 66% of jobless residents received unemployment benefits. In Florida and North Carolina, where 17% and 22% of residents are Black, respectively, less than 10% of people out of work receive jobless aid.

Then there’s the issue that each state determines how much of a worker’s previous income to replace through benefits. While the national average unemployment benefit replaces 47% of a worker’s income, many Southern states offer less, such as in Louisiana, where unemployment replaces 36% of lost wages. Seven Southeastern states cap their benefits maximum to $350 per week or less.

Low benefits payouts, combined with hard-to-navigate filing systems, further discourage workers from applying for aid.

“If you live in a state where benefits tend to be low, part of that is to discourage takeup,” Spriggs says. When applying for aid seems next to impossible, “people figure, ‘Why am I going to bother with this?'”

History of discrimination means Black workers are more likely to be paid less, unemployed

Given the immediate threats during the pandemic-induced recession, economists say lawmakers must provide more funding in the next round of relief that can better support jobless individuals, particularly Black, Brown, Indigenous and female workers.

“It’s important we concentrate on the $600 because it will cause economic catastrophe if we don’t put it back in place,” Spriggs says. He adds that upcoming legislation should extend benefits for the 40% of unemployment recipients under PUA, which supports workers who don’t have the traditionally required earning history to receive aid, including freelance, self-employed, gig and part-time workers — many roles in which Black workers are overrepresented.

“The share of workers getting Pandemic Unemployment Assistance clearly points to the gap in the regular state programs that ignore workers and a number of low-wage industries,” Spriggs says. “It shows we could and can devise access to programs to insure low-wage workers. As much as we’re concentrated on the $600, if we forget in December that the bulk of unemployed workers won’t have access to any assistance, it’s going to be a very slow recovery.”

Economists have also called for legislators to include significantly more aid to state and local governments, where women and Black workers are overrepresented, to avoid budget shortfalls and staff cuts.

‘We have to reimagine unemployment after this crisis. It’s not up to the task’

Spriggs says voters should urgently be thinking about the December 31 expiration of existing relief efforts, given lawmakers’ willingness to let the $600 benefit expire at the end of July. “The House passed the HEROES Act to resolve this July deadline in May, and here we are in August, at almost the same distance to December,” Spriggs says. “If people aren’t discussing how we’ll extend that, it’s a real danger.”

The Senate failed to take up the House’s May HEROES Act and instead unveiled its own HEALS Act with slashed jobless aid through 2020. In recent weeks, Congress and White House officials have not made progress on a new stimulus package. On August 8, President Trump signed a memorandum to create a new $300 supplemental wage to some jobless workers, which has been taken up in more than half of states. However, the program excludes workers who earn less than $100 per week in benefits, has taken several weeks to reach residents and experts question its viability long-term.

Speaking of citizens frustrated at lawmakers’ lack of urgency to pass a new deal, “this election means everything to them,” Spriggs says. “They need to be paying attention to who in Congress is taking the unemployment situation seriously, and they need to understand their vote matters.”

In the long-term, he says only drastic changes to state unemployment systems can increase racial parity in who qualifies for and receives jobless aid.

“State agencies aren’t good at monitoring issues of discrimination,” Spriggs says. “Until we hold them accountable for monitoring it, they’re not going to. They’re going to have to do a better job collecting that data [on race],” as well as increase monitoring of employers who disproportionately deny jobless claims among Black workers.

“We have to reimagine unemployment after this crisis,” Spriggs says. “It’s not up to the task.”

Check out: Americans spend over $5,000 a year on groceries—save hundreds at supermarkets with these cards

Don’t miss:

New $300 boosted unemployment arrives in Arizona, but not without headaches and confusion

More than half of states are now approved for the extra $300 per week in unemployment insurance

Nearly half of all furloughed workers now believe their temporary layoff will become permanent