House antitrust panel nears final steps in its investigation of Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google

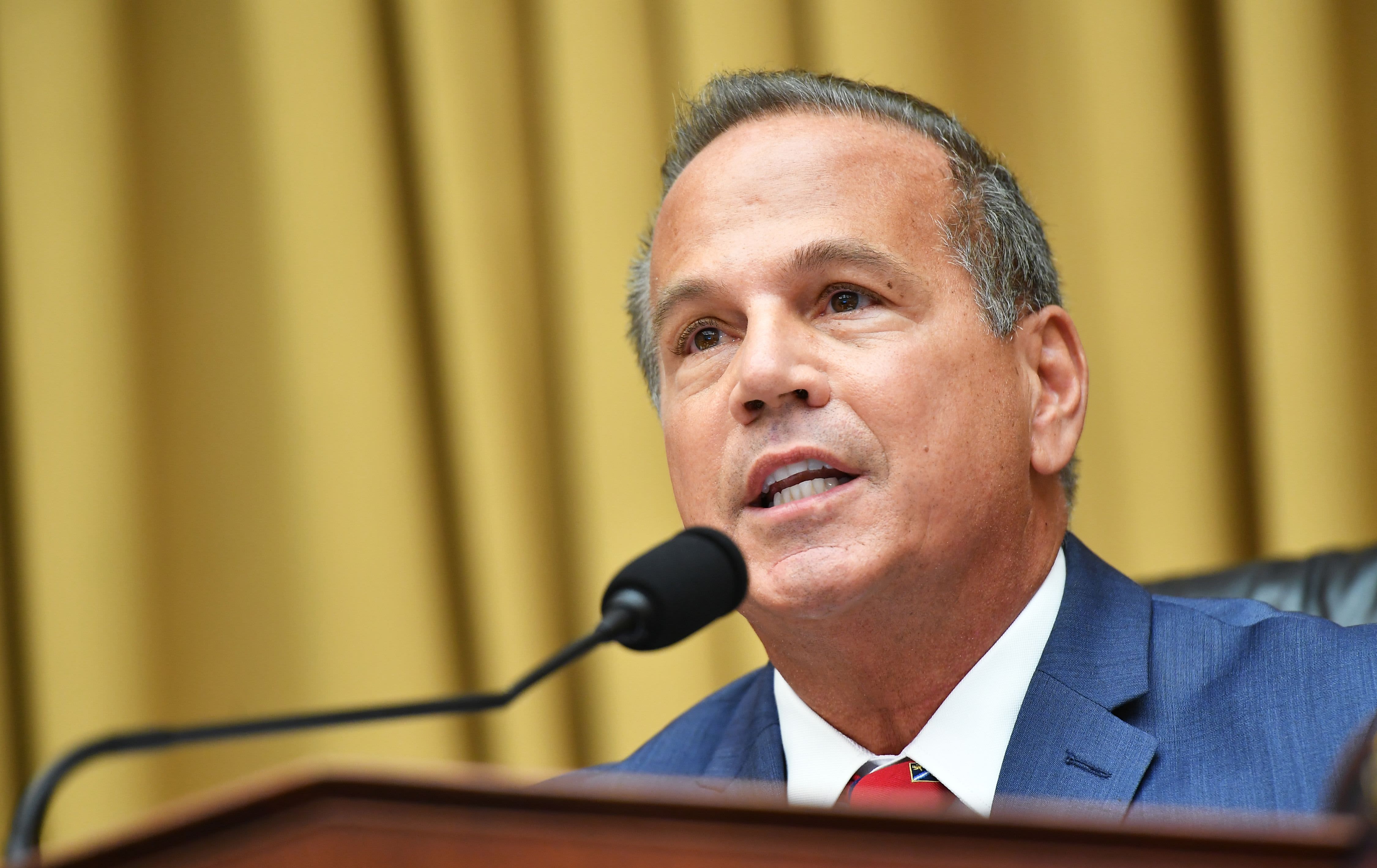

House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law Chair David Cicilline, D-RI, speaks during a hearing on “Online Platforms and Market Power” in the Rayburn House office Building on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC on July 29, 2020.

Mandel Ngan | AFP | Getty Images

Congress’ more than year-long investigation into four of the world’s most valuable tech companies is nearing its final stages, paving the way for new legal proposals that could drastically alter antitrust enforcement in the U.S. for the years to come.

On Thursday, the House Judiciary subcommittee on antitrust held its seventh and final hearing in a series examining the health of competition in digital markets and the business practices of Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google. The event was not as splashy as the subcommittee’s July hearing featuring the four tech CEOs and it also took about half the time.

But the nitty-gritty legal questions at this latest hearing displayed a group of lawmakers nearing the final stage of a long-awaited conclusion to their tech probe.

Chairman David Cicilline, D-R.I., summarized the recurring themes from the expert witnesses at the end of the hearing for how to reform the laws. Those themes included:

- Shifting the burden to dominant companies to prove their mergers will not harm competition, rather than forcing investigators to prove that a merger will harm competition.

- Separating different lines of business to weed out conflicts of interest.

- Beefing up resources at enforcement agencies.

- Prohibiting companies from “discriminatory behavior.” (He didn’t expand on this point, but could have been talking about how companies promote and price their own products.)

- Reversing court decisions that have “changed the intention of Congress” on antitrust law.

A congressional aide for a Democratic member of the Judiciary Committee, who was not authorized to speak publicly on the process, told CNBC that committee members anticipate reviewing the report in the coming days before releasing it publicly.

So far, it seems the subcommittee staff has held the report closely. But Rep. Ken Buck, R-Colo., said in an interview Wednesday that, based on conversations with Cicilline and staff, he expects it will include an overview of the investigation’s findings as well as broad legislative recommendations. Buck had not yet seen the report as of Wednesday.

Subcommittee Ranking Member Jim Sensenbrenner, R-Wis., who does not support updates to the antitrust laws, said in his opening testimony that enforcement of existing laws needs to step up. But he also noted reports that the Justice Department may soon bring an antitrust case against Google as evidence that change is already underway.

What experts want

Thursday’s hearing featured a panel of antitrust experts who offered advice and feedback to lawmakers on what they should consider in their reforms.

For example, Bill Baer, a former antitrust chief at both the Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice, told lawmakers it had become “nearly impossible” for enforcers to challenge mergers of potentially competitive nascent players. He and others on the panel suggested shifting the burden from the government to dominant firms to prove their deals would not harm competition.

Fordham Law Professor Zephyr Teachout discussed the need for a structural separation of businesses that pose a potential conflict of interest. Cicilline recently discussed a similar idea of a “Glass-Steagall” type of reform, referring to the legislation that separated banks’ commercial and investing arms. That could mean separating Amazon’s marketplace for third-party vendors from its private label business, where it sells Amazon-branded products, or limiting Apple’s ability to include and promote its own apps on its App Store, for instance. Enforcement advocates, including Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., have argued that dominant firms can favor their own businesses when they are allowed to both own a platform and participate on it.

‘Bipartisan sweet spot’

As the investigation reaches this late stage, several committee members have publicly praised the continued bipartisan nature of the investigation. Buck told CNBC that such bipartisanship is important to send a strong message to the tech companies.

“I think the next stage is to issue a report and to make it as bipartisan as possible and make sure that we are not sending a message to the tech companies that there is a division on Capitol Hill,” Buck said. “We need to be united in this and make sure that we do not go off into tangents on either side.”

Rep. Jim Jordan, R-Ohio, the top Republican on the Judiciary Committee, and Rep. Greg Steube, R-Fla., focused their questions at Thursday’s hearing on alleged conservative bias by the tech platforms, spending more time discussing potential reforms to tech’s legal liability shield, Section 230, than the antitrust laws. But Buck and Rep. Kelly Armstrong, R-N.D., kept their questioning more narrow to competition policy and displayed their support for reform and adding resources for enforcers.

Buck said in the interview that while he is a “small government Republican” and “fiscal conservative,” he believes the budgets of the FTC and DOJ don’t allow sufficient staff for investigations of resource-rich firms. However, he does not support the creation of a new agency to regulate the tech industry like some Democrats do.

Formal bills, if they are even introduced in the coming months, will likely not make it far until the next Congress, during which there will be many priorities jostling for attention. But Thursday’s hearing shows sustained interest from members of both political parties over the long investigation.

To pass legislation, Buck told CNBC, it will be important for lawmakers to focus on the areas on which they can agree.

“I think we really need to find this bipartisan sweet spot and recommend fixing some targeted areas that would enhance the role of the government in promoting competition,” he said.

WATCH: How US antitrust law works, and what it means for Big Tech