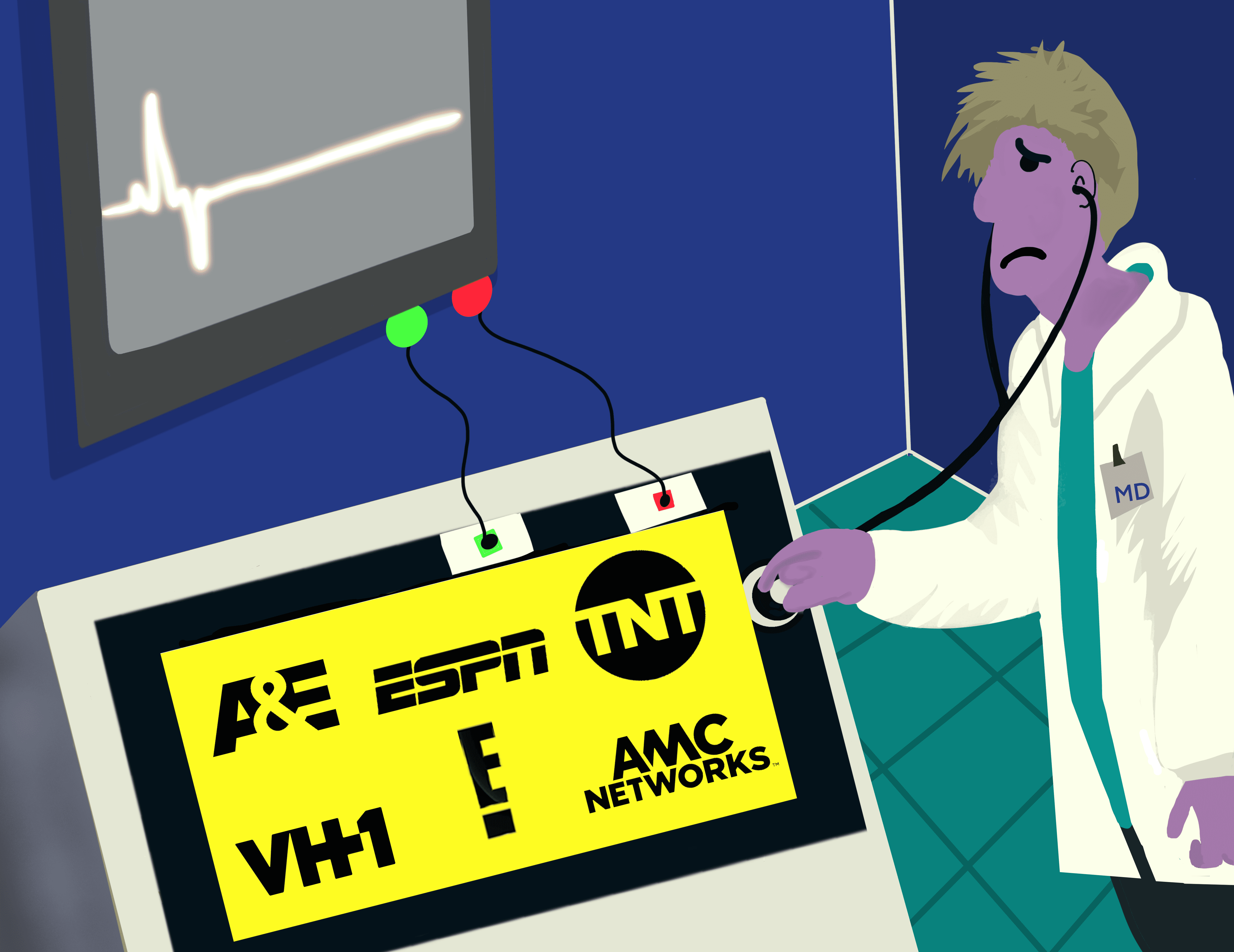

Media executives are finally accepting the decline of cable TV as they plot a new path forward

Josephine Flood | CNBC

There’s a quiet consensus emerging in the hallways and boardrooms of American media companies.

They expect about 25 million U.S. households to cancel their pay-TV subscriptions over the next five years. This is on top of the 25 million homes that have already cut the cord since 2012. At least three major media companies now expect pay-TV subscriptions to stabilize around 50 million, according to people familiar with the matter, who declined to speak on the record because their company plans are private.

The projected decline in subscribers will mean a drop of about $25 billion in cable subscription revenue plus associated advertising losses for the largest U.S. media companies, including Disney, Comcast‘s NBCUniversal, AT&T‘s WarnerMedia, ViacomCBS, Fox, Discovery, Sinclair and AMC Networks.

This assumption has created a tectonic shift in the media industry. In the last three months, Disney, NBCUniversal, WarnerMedia and ViacomCBS have all announced major reorganizations. They’ve replaced old leaders, consolidated divisions, laid off tens of thousands of employees, and pivoted to streaming video.

American viewers can now choose among streaming services from most of the major players, including Disney+, WarnerMedia’s HBO Max, NBCUniversal’s Peacock, ViacomCBS’s Paramount+, Discovery+ and AMC+, at prices ranging from free to $15 month. All have launched in the last year or are coming in early 2021.

The plan is simple enough: Hope enough people sign up for subscription streaming services to make up for cable TV subscriber losses.

Why streaming might not save U.S. media

In 2015, Time Warner CEO Jeff Bewkes sat down with his executive team to talk about the future of TNT and TBS, the two flagship Turner entertainment cable networks.

For more than a decade, TNT and TBS ratings had lived off re-runs of hit broadcast shows — “Seinfeld,” “Friends,” “Family Guy,” “The Office” and so on. Now there was a problem. Netflix, Hulu and Amazon Prime Video had acquired digital rights to the same catalog of re-runs. Instead of having to tune into a cable network at a certain time, viewers could consume entire seasons of shows on demand without suffering through commercial interruptions.

“The streamers simply had superior capabilities,” said Bewkes in an interview. “The basic cable networks didn’t have full video-on-demand. We were reliant on advertising. It’s not that the streamers had superior programming, they had superior technology.”

Jeffrey ‘Jeff’ Bewkes, chairman and chief executive officer of Time Warner Inc., listens during a Senate Judiciary Subcommittee hearing in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Wednesday, Dec. 7, 2016.

Andrew Harrer | Bloomberg | Getty Images

A year later, Bewkes agreed to sell Time Warner to AT&T for more than $100 billion including debt. The following year, Rupert Murdoch pulled the rip cord, selling the majority of Fox’s assets for more than $70 billion to Comcast and Disney. Both men seemingly came to the same conclusion: The cable bundle had peaked. The longer they waited, the less their assets would be worth.

The cable bundle means that consumers can’t select and pay for cable TV channels a la carte. Instead, they have to buy dozens at a time. Media executives have long referred to it as the golden goose.

Media companies who sell channels into the bundle get paid whether or not anyone is watching. Don’t watch sports? You’re still paying $20 or $30 a month (depending where you live) for sports in a standard cable bundle. Don’t watch reality TV? You’re still paying for Bravo, E!, TLC, HGTV, and so on.

Better yet, every popular cable network has been nearly guaranteed distribution — and payment — because if an operator like Comcast decided it didn’t want to pay for ESPN, competitors such as Dish and AT&T’s DirecTV could steal its sports-hungry customers.

“Media companies have had a fabulous distribution system for decades,” said Tom Rutledge, CEO of Charter Communications, the second-largest U.S. cable company. “Every distributor had to carry their product, because if they didn’t carry networks, the competition would. In a direct-to-consumer world, the whole ecosystem is smaller. It doesn’t mean you can’t win, but there will be a lot of losers.”

Some streaming services already have enough library content to thrive in this smaller ecosystem of streaming services.

Disney+, with decades of kid-friendly movies and TV shows plus the Pixar, Star Wars and Marvel franchises, has already surpassed 60 million subscribers, hitting the low range of its 2024 goal in less than a year.

What about the smaller players? Can they compete for new originals against Netflix, Amazon and Apple — companies with massive balance sheets — to have the best content going forward?

“The answer is no,” said Bewkes. “These companies are competing against Netflix and Amazon, who have massively more scale for both subscription and advertising at a global level. They’re all going to be collapsed. Only Disney will have enough subscribers and global scale under a distinctive family brand to make it.”

Even Disney will need to keep growing those numbers to make up for impending cable TV losses. Each lost cable customer costs the company about $17.62 each month — excluding advertising — according to Kagan estimates. Most of that has to do with ESPN’s value, which commands about $10 per month per subscriber on its own.

Disney charges $6.99 per month for Disney+ and bundles ESPN+, Hulu and Disney+ together for $12.99 per month. And Disney+ doesn’t include advertisements.

At those prices, a one-for-one swap of a cable customer for a streaming customer will mean less money for Disney. This doesn’t even account for potential revenue loss from password sharing. While stealing cable TV is quite difficult, it’s a lot easier to share a password for a streaming service, and it’s more common among younger viewers. In 2019, research firm Magid estimated 35% of millennials share passwords for streaming services.

“It’s just too easy to get the product without paying for it,” said Rutledge.

Brian Roberts, chairman and CEO of Comcast Corp and Tom Rutledge, president and CEO of Charter Communications.

Getty Images

Moreover, a vicious cycle is settling in that could accelerate cable bundle defections. Distributors like Comcast and Charter no longer care that much whether or not a customer buys traditional pay-TV. The price of a video bundle has gotten so high, there’s little margin for them — especially compared to broadband internet service.

“You get to that point of financial indifference, then you’re seeing the EBITDA margins go in the right direction and continue to increase,” Comcast CEO Brian Roberts said last month at the Goldman Sachs Communacopia Conference. “That’s one of the big pivots of Comcast the last decade.”

So instead of threatening blackouts to lower rates, pay-TV operators are accepting rate hikes, passing them along to subscribers, and accepting the fact that price-sensitive customers will cancel TV and go to internet only.

Meanwhile, media companies are shifting their best content to their new streaming services. The result for consumers is higher and higher prices for lower and lower quality.

And certain networks, like ESPN, which keep millions of Americans hooked to cable today, may need to pull back on programming costs if too many people cancel. That will only cause more people to cancel. Stabilizing at 50 million may be a pipe dream.

“The only thing left holding the bundle together today is sports,” said former AOL CEO Jonathan Miller, who stepped down from the board of AMC Networks in July. “There is nothing any of the networks can do about it. The only question now is how far does it fall and how fast, and is there a bottom. And I don’t know if there’s a bottom.”

Then again: Why streaming might save U.S. media

The best path forward for media companies is if Americans suddenly decide to stop canceling cable. That cash flow can then be redirected to streaming services as the industry’s new global growth engine. There’s at least a chance a combination of live news and sports, combined with inertia and laziness, can keep a diminished bundle alive.

Charter actually added 102,000 pay-TV subscribers in the second quarter. But that’s almost certainly an anomaly. Comcast reported a net loss of 477,000 video subscribers (427,000 residential) last quarter. AT&T, which owns DirecTV, reported a net loss of 886,000 video subscribers in the same quarter.

Media companies could team up and decide to recreate the bundle model with their new streaming services. Unlike the cable bundle, a streaming bundle wouldn’t eliminate the “make your own” option, as each service can be purchased a la carte. But investors may not mind if companies take revenue discounts if it means growth.

It’s also possible that Wall Street will give a window to legacy media companies to let them spend billions on streaming content, giving them a greater chance of finding the next “must-see” shows. Activist investor Dan Loeb has already called on Disney to eliminate its annual dividend and use the cash on original content spend for streaming services.

“By reallocating a dividend of a few dollars per share, Disney could more than double its Disney+ original content budget,” Loeb wrote in an October letter to Disney CEO Bob Chapek. “These incremental dollars would, based on our analysis, generate returns that are multiples of the stock’s current dividend yield.”

Netflix has proved that market validation is more important than business fundamentals in terms of growing valuation. Netflix has burned through billions in cash for years, spending borrowed money on content to grab subscribers, and investors haven’t cared.

Maybe media companies won’t have to worry about how to replace revenue from each cable subscriber with a corresponding streaming subscriber. Perhaps simply showing there’s a new growth engine that looks more like Netflix will push investors toward valuing the entire industry higher.

Right now, the market doesn’t seem to think existing media companies are capable of this. Discovery’s enterprise value/EBITDA multiple is 3.5. AMC’s multiple is 2.3. Those are terminal values. The average S&P 500 company typically has a multiple between 11 and 15. Netflix is valued at 33.5.

But even if the market is right and media companies can’t stabilize revenues in the shift to streaming, that’s not a death knell. Profit and cash flow could conceivably rise as cable networks are folded and jobs are eliminated. Sometimes industries need a refresh, but it’s not necessarily a funeral.

There’s also the “Underpants Gnome” argument. In a 1998 episode of Comedy Central’s “South Park,” a group of gnomes steal people’s underpants. Their plan is: Phase 1: Collect Underpants, Phase 2: ? and Phase 3: Profit.

A lot will happen between now and 2025. New technologies emerge. Tastes and habits are fickle. Companies acquire other companies. CEOs change.

It’s hard to predict the future. Sometimes fighting to survive turns into actual survival.

The likely endgame

Cable networks continue to be profitable, and recent distribution deals ensure they’re not going anywhere.

Still, some companies probably won’t make it in a streaming world alone. They may need to merge to survive.

Billionaire media magnate John Malone has mused about the consolidation of networks for years, advocating putting together “free radicals” to merge assets. AMC’s “The Walking Dead” may not be enough to keep a streaming service viable, but if joined with Lionsgate‘s “Mad Men,” MGM’s “James Bond,” and Discovery’s “Top Chef” and “Deadliest Catch,” such a service may have enough content to remain relevant for a while. Malone has a stake in Discovery and also owns some of Charter — either of which could act as the vehicle to buy up cheap networks.

The problem is many of these companies may have missed their ideal window to sell. Disney executives looked at the media landscape after its deal for Fox and decided it had no interest in acquiring any existing traditional media company’s content, according to a person familiar with the matter. If a technology company or large media company such as AT&T or Comcast bought a smaller legacy media company today, the acquirer’s shares would likely plummet.

Instead, what’s likely to happen in the next five years is the systematic consolidation and elimination of cable networks. NBCUniversal and ViacomCBS are both considering shuttering networks, though nothing is imminent or particularly close given current distribution deals, according to two people familiar with the matter.

“Media companies can consider consolidating underperforming networks with core channels, hoping to extract additional carriage revenue from a beefier network,” said Kirby Grines, founder and CEO of 43Twenty, a consultancy and marketing firm that provides streaming video strategy advice. “Consumers have loyalty to content and perhaps the companies they transact with. I’m not sure where networks fit into that equation, but it’s somewhere in a meaningless middle.”

ViacomCBS has already identified CBS, MTV, Nickelodeon, Comedy Central, Smithsonian and BET as its tent-pole brands, which show up in the company’s CBS All Access streaming application (soon be renamed Paramount+). Other ViacomCBS networks — VH1, Logo, PopTV, CMT — are absent from the streaming platform. That may be a sign they’re at risk of eventual shutdown or rebrand.

Still, most media companies will try to perform a delicate dance, shifting most premium content to streaming while still giving some A-level shows to networks to buoy the bundle for as long as possible.

The forcing function on change will be Wall Street. If valuations keep declining, media companies will have to act.

LightShed’s Greenfield recommends a ripping-off-the-band-aid approach: Divest the networks now.

“Disney should divest its broadcast and cable networks, Comcast should divest the NBCUniversal cable networks, and there’s no reason why AT&T needs to own the Turner networks,” Greenfield said. “Cable networks are structurally broken.”

Divested and merged media companies will lead to more robust streaming services. This is why Disney agreed to buy Fox’s entertainment assets, including “The Simpsons” and movies such as “The Shape of Water” and “Avatar.”

But it may also accelerate the death of cable TV.

“The total bundle is going to shrink,” said Bewkes. “Whether it disappears, I don’t know.”

Disclosure: Comcast’s NBCUniversal is the parent company of CNBC.

WATCH: Disney announces a major reorganization to focus on streaming — here’s what it means