After suing Facebook, the FTC has a chance to show critics it’s not toothless

With its groundbreaking antitrust lawsuit against Facebook, the Federal Trade Commission is facing more than just a fight against a multi-billion dollar tech giant — it’s battling to regain credibility that could determine its future.

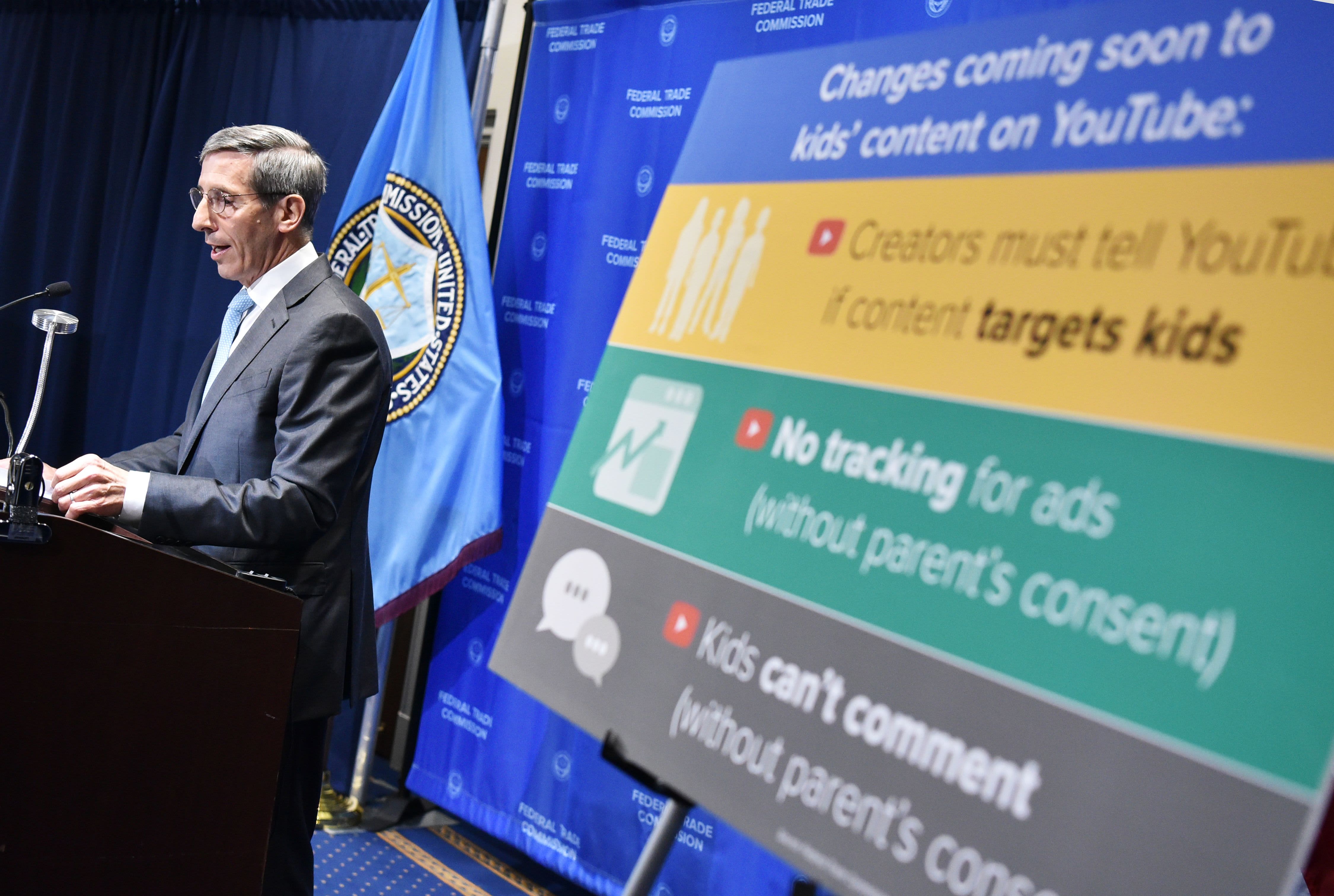

The FTC was roundly criticized by lawmakers on both sides of the aisle following privacy settlements tech hawks deemed to be toothless. In July 2019, the agency settled a privacy investigation into Facebook following the Cambridge Analytica scandal for $5 billion, representing about 9% of the company’s 2018 revenue. Shortly after, it settled alleged violations of children’s privacy on Google-owned YouTube for $170 million.

“The FTC is foolish & foolhardy to rely on money alone to punish decades of past privacy violations & ongoing profiteering,” Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., tweeted at the time of the Facebook settlement.

Long before that, the agency closed an investigation into Google’s competitive practices without bringing charges recommended by staff. Nearly a decade later, the DOJ has taken up competition charges against the search giant.

The perceived failure of the commission to hold tech giants to account in the eyes of some lawmakers has threatened the FTC’s very existence. Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., proposed last year relegating the entire agency to become a division of the Justice Department and consolidating all of its competition enforcement power under the DOJ Antitrust Division.

That gives the FTC’s actions against Big Tech firms added significance. The FTC is different from the DOJ in that it is independent from other branches of government. FTC Chairman Joe Simons testified last year that structure is actually what makes the agency so valuable, though he agreed with DOJ antitrust chief Makan Delrahim that splitting antitrust enforcement power between two agencies causes inefficiencies.

That was the backdrop in which Simons made the decision to break from his Republican peers to be the deciding vote in bringing an antitrust case against Facebook in federal court. Just about a week later, he joined most of his colleagues in voting for a broad study into the privacy practices of nine tech companies.

Simons made it a priority during his time at the helm of the commission to expand and concentrate its expertise in the tech sector, said a person familiar with the FTC’s thinking who was only authorized to speak on background. That meant creating a Technology Task Force within the commission, which is now known as the Technology Enforcement Division.

It was within this context that the FTC decided to pursue an antitrust investigation into Facebook. Facebook first disclosed the investigation last year, just after its $5 billion fine from the agency. The FTC typically opens conduct investigations after one of three things happen, according to the source: 1) someone complains about a company’s behavior to the commission, 2) states or the Justice Department refer a case to the agency, or 3) new information comes to light through public reporting.

For Facebook, it was the third option that prompted the investigation, the source said, declining to specify the new information that set it in motion.

The FTC’s decision to press charges in the Facebook case was applauded by its recent critics. The lawsuit is a sweeping indictment of Facebook’s operations and acquisition strategy, which the commission argues demonstrates its attempts to illegally maintain monopoly power in personal social networking. The case focuses primarily on Facebook’s acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp — two mergers the FTC got to review before they were consummated.

Facebook’s chief counsel called the lawsuit an attempt for the government to get a “do-over, sending a chilling warning to American business that no sale is ever final.”

While as a matter of law, the FTC’s decisions not to block the mergers at the outset extend no presumption of legality, Facebook will likely continue to press the point in court, according to antitrust experts.

“Certainly some of these warning signs were there,” Delrahim, the DOJ antitrust chief, said in an interview with CNBC this week. “If you go back to Microsoft, the Federal Trade Commission also looked at that and didn’t bring a case until the Justice Department in the Clinton administration took it up under Joel Klein and brought the case. That is not an FTC versus DOJ comment, but it is a commentary that sometimes when you don’t have decision making in an executive, decision making becomes much more difficult and may not be optimal.”

Delrahim favors a structure where responsibility is concentrated in one individual, like at the Antitrust Division, where he has the final say in bringing an enforcement action. At the FTC, by contrast, five commissioners must vote on whether to bring an action, with no more than three commissioners at a time coming from the same political party.

“There’s no question in my mind that the right thing to be doing is combining the two agencies, but that’s not a decision that I get to make,” Delrahim said.

The source familiar with the FTC’s thinking defended the commission’s structure, saying the bipartisan tradition of the agency means that cases go through rigorous debate and vetting before they ever reach public eyes, making them stronger along the way. They pointed to the FTC’s litigation record, rebutting the idea that the deliberative model has slowed down its efforts. The agency has brought important, if less widely followed, antirust cases in the tech sector over past several years, like against chipmaker Qualcomm and e-prescribing platform Surescripts, they added.

When it comes to the Facebook case itself, Delrahim described many parts of it as “sound,” particularly the aspect involving Facebook’s alleged use of its application programming interfaces (APIs) to cut off competitors from its platform. He also defended the legitimacy of privacy as an element of potential consumer harm.

“The issue of privacy as a quality element of competition is a very legitimate issue,” Delrahim said. “A lot of people over this debate have confused antitrust standards with only looking at price effects and that’s just not true.”

Just bringing such a sweeping lawsuit is already a significant step for the FTC. But it comes with high stakes. If the government fails to prove its case in court, it risks creating more case law that will be unfavorable to future monopoly challenges, possibly further chilling enforcement in the area.

But if it wins, it could usher in a new era of antitrust enforcement.

“If you never bring a Section 2 [Sherman Antitrust Act] case as the government, you start to embolden monopolists,” said Sam Weinstein, a former DOJ antitrust attorney who now teaches at Cardozo Law. “They start to think, ‘we can kind of do whatever we want here, the government is afraid to litigate.'”

Weinstein said the cases themselves “are terrible PR” for the companies and shows peers “the government has the will to do this. It’s not longer theoretical; it’s happening.”