An underperforming Exxon Mobil faces a new climate threat: Activist hedge fund investors

Exxon Mobil is poised for a new role in a changing world it doesn’t want: target and test case for a new form of combined attack from activist hedge funds and long-term impact investors focused on sustainability and climate change. A newly formed activist investor group, Engine No. 1, announced plans on Monday to seek four board seats at the oil and gas giant, and underlying the effort are both short-term and long-term goals to change the way Exxon approaches the energy business at a time of rapid transition forced by fears about carbon emissions.

The activist firm — which includes founders from successful activist hedge funds including Partner Fund Management and JANA Partners — thinks the time is ripe for an overhaul of Exxon’s management. The market stats cited in its letter to Exxon’s board highlight a significant drop in operating performance and “dramatic” decline in Exxon’s stock value in recent years as many investors have lost faith in the company.

Total shareholder return, including dividends, over the last 10 years has been negative 20%, versus 277% for the S&P 500. Its total shareholder return for the prior 3-, 5- and 10-year periods trailed energy peers, as well. One sign of how much Wall Street is shying away from Exxon Mobil: a lack of analysts recommending the company.

“Despite the Company’s dramatic decline in value, as of last week only 14% of sell-side analysts covering the company rated it as a “buy,” the letter noted.

Where activists are meeting climate investors

Activists see opportunity in short-term value creation for a company that has been depressed by factors including poor capital spending decisions during a cyclical downturn. Institutional investors, including pension funds, also see an opportunity to get an oil company that has ignored climate change engagement efforts to finally pay attention. And the big three index fund companies — BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street Global Advisors — represent many individual investors who are increasingly worried about what may be a threatened Exxon Mobil dividend.

Engine No. 1 already received the backing of California pension giant CALSTRS, which invests on behalf of the state’s teachers. CalSTRS chief investment officer Chris Ailman told CNBC on Monday that the pension fund is becoming more of an activist shareholder after previous work his pension fund has done with the Climate Action 100+ coalition to engage with Exxon has not worked.

“With Exxon it has been very unsuccessful, sadly, trying to get their attention, change their behavior,” Ailman said. “This company is just throwing money after projects that are not going to be successful. … When I think about Exxon, it has been focused in on drilling every last molecule of carbon. They need to wake up and realize the future is different.”

Engine No. 1 referred a call to its letter to Exxon’s board and declined further comment. Exxon has said it is studying the letter, but did not respond to a request for additional comment.

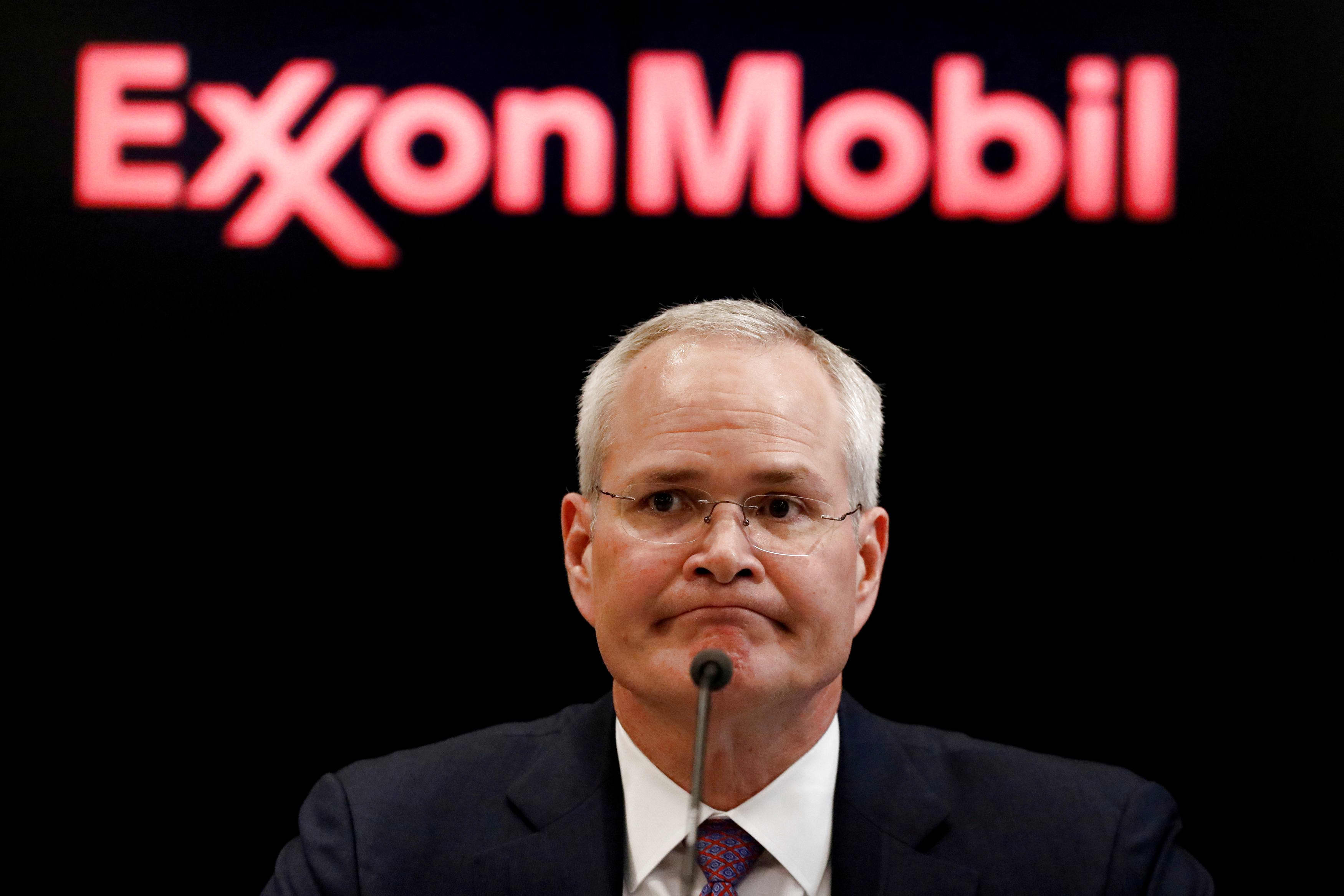

Darren Woods, CEO of Exxon Mobil Corporation, who faces a new activist fund campaign targeting the board he heads. “They are going to have to get more reliable on the results,” says Peter McNally, energy analyst at research firm Third Bridge.

Brendan McDermid | Reuters

Exxon Mobil would have been an unthinkable target for activists for a long time, given its size.

“This is not a $500 billion market cap company any more,” said Peter McNally, energy analyst at Third Bridge Group.

But even with its diminished market cap, the activist goals won’t be easy to accomplish. Exxon’s market cap is now under $200 billion, but CalSTRS has a $300 million holding and it has been reported that Engine No. 1 has a $40 million stake.

Ailman said the key is getting the big index funds that hold the most shares and represent the mass investment universe on board with the plan. He said BlackRock CEO Larry Fink was the first person he emailed about the activist campaign, though he has not received a reply yet.

One of the Engine No. 1 founders is a former senior executive from BlackRock’s iShares ETF business, Jennifer Grancio.

“Retirees own the stock for the dividend and and that dividend is threatened.That dividend will be slashed unless they change,” Ailman said.

Exxon Mobil shares have been weakened by low crude oil and natural gas prices, as well as the Covid-19 downturn, but it has been a laggard in its energy sector peer group in recent years.

The top three index fund companies all supported a proposal to require Exxon to release a climate planning report in 2017, a proxy vote that was seen as a watershed at the time, but has turned into a source of frustration for investors with Exxon delivering little in the way of substantial reporting.

“There is abysmal shareholder sentiment around this company,” said one institutional investor.

Ailman said in addition to getting the largest investors on board, it will be key to to talk to the proxy advisors which make recommendations on shareholder meeting resolutions and board director nominations. Exxon Mobil’s annual meeting is set for early May.

“This is a real game changer,” said Jackie Cook, director of sustainable stewardship research at Morningstar, who has tracked shareholder climate proposals for years. “Challenging fossil fuel companies on their climate governance should be easy pickings for well credentialed activist investors – especially with the backing of large pension funds. There’s no evidence that Exxon’s board, as it’s presently structured, is capable of making a dramatic turnaround.”

The battle over Exxon Mobil’s board

Exxon’s board of directors is a Who’s Who of blue-chip corporate executives, but none from the energy industry.

Engine No. 1 has recommended executives with expertise in oil and gas, as well as renewable energy, including former CEOs of refining company Andeavor (formerly Tesoro) and Danish wind power company Vestas.

“Replacing board members is last step investors would take, but we’ve tried all the more traditional avenues of pressure,” said Andrew Logan, who heads oil and gas research at sustainable investment advocacy group Ceres. “It took us a long time to get to the point of investors giving up on engagement and thinking the company will ever change on its own.”

As disruption across sectors of the market and in the economy accelerates, the interests of activists are more likely to be aligned with impact investors across a wider set of companies, including in technology, for example, where JANA Partners targeted Apple over issues related to child safety and health in 2018. As well as on issues beyond climate, such as income inequality.

Logan said there is a compelling thesis today for a convergence of traditional investor activists and climate-aware investors, but whether it goes beyond the energy sector is still to be determined, and Exxon is the clearest case even within oil and gas sector for a new kind of campaign.

“There’s been a lack of capital discipline for a long time. Climate investors and activist investors are thinking about return and cash to shareholders and are aware of the looming risks. Exxon is the place where it all came together more evidently. Even in oil and gas it has been a laggard and the board is part of the problem. … the board is the classic example of a collection of people who on their own are impressive but together lack experience to really run a complicated company at a time of rapid change.”

McNally said it would have been easier for Exxon to argue against adding energy expertise to the board at a time when it was performing better. “They’ve opened themselves up to the criticism,” he said.

Last week, Exxon Mobil announced a writedown of $20 billion, a focus on a smaller set of top assets, and a 2022-2025 capital spending plan reduction to $20-$25 billion, but critics say the moves are too little, too late and merely a recognition by Exxon management of what everyone outside the company already knew.

“For a very long time when it had a valuation premium to peers, people thought the management had a secret sauce, people thought they couldn’t challenge management, and this management has lost luster,” Logan said. Writing down assets in the high-profile and expensive acquisition of XTO Energy after a decade, and after many years of criticism over how much it paid to play catch-up in fracking through the 2010 deal, is another example of how “extremely resistant Exxon is to outside criticism,” he said, and he added, it is a stubborn streak that also cost shareholders’ billions of dollars.

Short-term and long-term plans of attack

An individual familiar with Engine No. 1 plan of attack said it has both short and long-term goals to create value in depressed Exxon shares. Cutting unproductive capital spending and tying management compensation to new performance metrics — CEO pay rose 35% in the past three years even as it trailed peers — can lead to the market giving the company a higher multiple, more in line with peers, in the near-term. But there also is a longer term goal of changing direction for a company that some investors worry will be worthless in the decades ahead as the world transitions away from fossil fuels.

That is not a strategy that will pay off in two to three years, but the new activist effort could be the beginning of a longer-term alliance with big institutional investors focused on energy transition and climate change. It may also — along with getting CalSTRS to join the effort early — help to bring more long-term investors and impact investors on board that otherwise might be skeptical of an activist being in it for the long haul.

“There are short-term steps that would benefit longer-term investors,” Logan said. “What makes sense for traditional activists will also help position the company better for a fast-changing future.”

It is not clear that even for those oil giants making bolder moves related to energy transition that the market will reward them. BP recently said it will transition to an integrated energy company with more focus on renewables, and as part of that plan it slashed its dividend, and its shares are still down significantly since that announcement. Year-to-date, its stock chart is no better than Exxon’s.

They’ve just dismissed climate out of hand and they need to at least raise questions, rather than dictate answers

Andrew Logan

Ceres

But the case made by oil companies, including Exxon, in the past that they need to invest where returns are highest is getting harder to make. Engine No. 1 noted in its letter to Exxon’s board that its return on capital invested in exploration and production has declined from as high as 35% in the decade between 2000-2010 to 6% in recent years.

Goldman Sachs analysts issued a report earlier this year that estimated Exxon’s returns on capital would be the lowest among its proxy peers. An analysis from energy consulting firm Wood Mackenzie over the summer found that ExxonMobil owned 60% of its peer group’s lowest margin assets by production.

“They’re not knocking the cover off the ball and the cost of capital keeps going up for oil and gas projects, and the dividend keeps needing to be funded,” said one investor who monitors Exxon Mobil closely.

The deterioration in the return on traditional projects makes Exxon more vulnerable to arguments that its stubborness in relation to energy transition investments is no longer supported by the numbers. And even if oil bounces back for a few quarters, the long-term crude pricing and demand outlook is likely to remain volatile.

Third Bridge Group’s McNally said decades of massive shareholder buybacks which have not helped to prop up the stock price, are among the signs that it is not delivering for shareholders. He also cites Exxon’s chemicals business, which from 2011–2018 averaged net income of $1 billion a quarter and has seen that decline precipitously, even before Covid-19. He noted that since 2017 the company has invested $25 billion in upstream projects but cumulative net income from that time through Q3 2020 was $8 billion.

“They are going to have to get more reliable on the results,” he said. “Exxon has always claimed they are good at the long term and seeing trends and investing through cycles.”

Investing based on which oil company is charting the right long-term path remains a difficult game. In the short-term, given declines in both Exxon Mobil and BP shares, paying a high price to get into renewables may not lead to immediate results in the stock market. And the energy sector remains a cyclical one tied to the prospects for the global economy. “We don’t know if shunning hydrocarbons is the right call,” McNally said.

Exxon can bank on natural gas prices recovering, demand coming back, and capturing a cyclical upturn with better management execution. “That’s clearer than trying to guess if peak oil is 2019 or 2025 or 2040,” he said.

But at the same time, Exxon fares poorly compared to Chevron in sentiment among top institutional investors, and the reluctance on Wall Street to give it shares a buy rating — which many other beaten-up oil stocks have received — indicates that its issues are not only related to a downturn in commodities. And it has fared poorly in comparison to several major oil and gas peers on a more simple metric: having any stated plan related to carbon emissions and climate change, and a future of potentially lower demand and crude prices.

Climate investors say Exxon has not even wrestled with the big questions, and in the least, the market may no longer let it get away with sticking its head in the sand. “They’ve just dismissed climate out of hand and they need to at least raise questions, rather than dictate answers,” Logan said.