Biden’s next fight: Anti-vaxxers jeopardize plans to protect U.S. against Covid

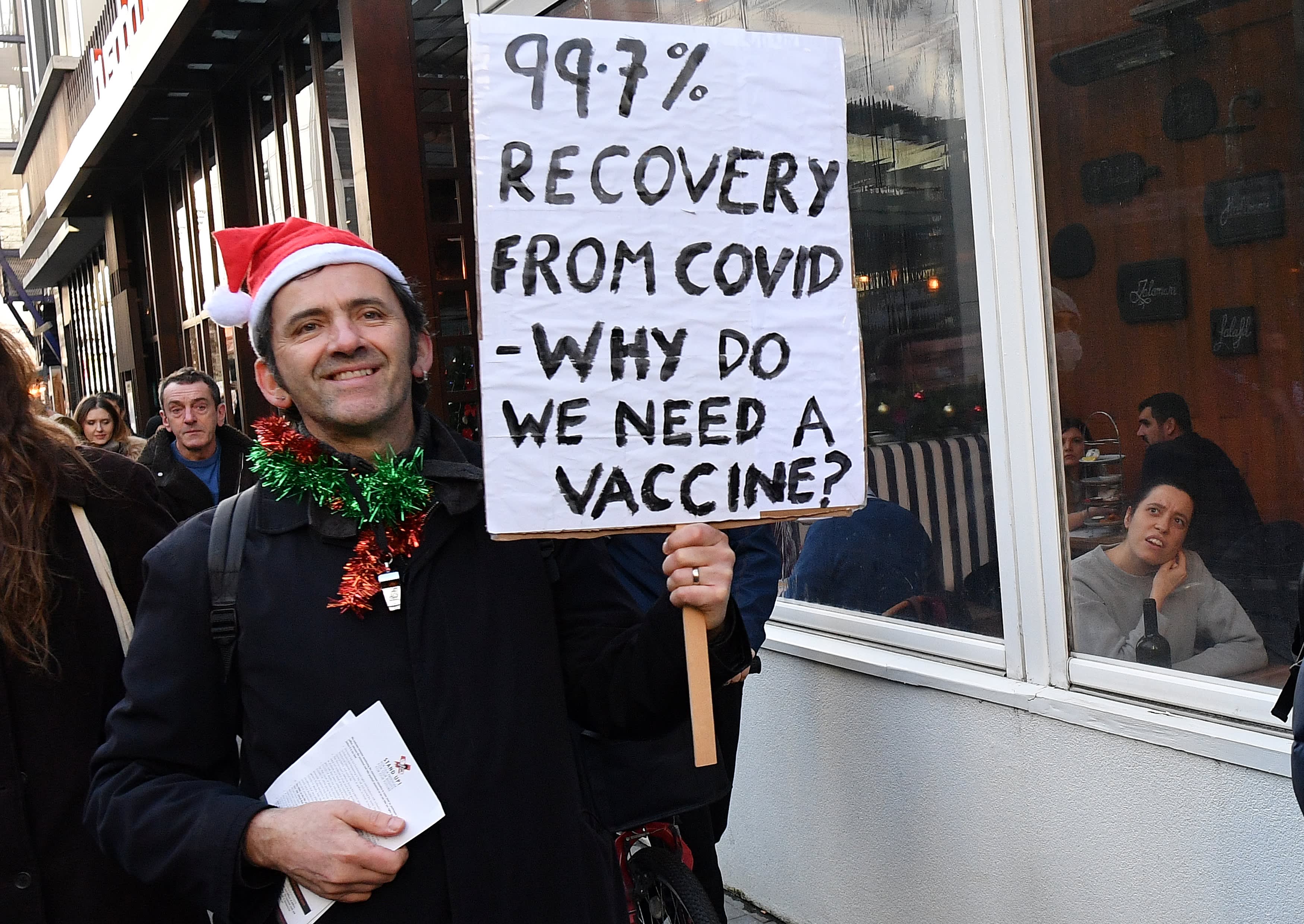

Demonstrator holding an anti-vaccine placard in east London on in central December 5, 2020.

JUSTIN TALLIS | AFP | Getty Images

Wendy Borger tested positive for Covid-19 at an urgent care center in Palmerton, Pennsylvania, on Dec. 28. She said she was fatigued, short of breath, and had a headache, heart palpitations and a fever of 103 degrees Fahrenheit. Her oxygen level dipped to 94%.

Borger, who is 50 and suffers from chronic bronchitis, said her lungs felt like a “weapon” when she walked down the stairs or even had a shower. It took almost two weeks before it didn’t hurt to breathe, she said. It’s been more than a month since her diagnosis, and she still isn’t fully recovered.

Despite her suffering, she still won’t get a Covid-19 vaccine shot.

“I’m not a believer in the flu shot, either. I just think that our body needs to fight off things naturally,” Borger, a self-described anti-vaxxer, told CNBC. “I mean, like me, you know, luckily I survived. It was bad, but I survived.”

As President Joe Biden works to ramp up the supply of Covid-19 vaccines in the United States, public health officials and infectious disease experts warn of another big challenge for the new administration: A significant portion of the U.S. population will likely refuse to get vaccinated.

Even though clinical trial data shows Pfizer‘s and Moderna’s vaccines are safe and highly effective, just under half of adults in the U.S. surveyed in December said they were very likely to get vaccinated, according to a new study from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s up from 39.4% of adults surveyed in September but still below the 70% to 85% scientists say needs to be vaccinated to suppress the virus.

That could potentially jeopardize U.S. vaccination efforts to control the pandemic, which has overwhelmed hospitals and taken more than 466,000 American lives in about a year. Without so-called herd immunity, the virus will continue to spread from person to person and place to place for years to come, scientists have said.

Herd immunity

Roughly 33 million out of some 331 million Americans have received at least their first dose of Pfizer‘s or Moderna‘s two-dose Covid-19 vaccines, according to data compiled by the CDC. And 9.8 million of those people have already gotten their second shot.

The goal, according to Biden’s chief medical advisor, Dr. Anthony Fauci, is to vaccinate between 70% and 85% of the U.S. population — or roughly 232 million to 281 million people — to achieve herd immunity and suppress the pandemic.

“The concern I have, and something we’re working on, is getting people who have vaccine hesitancy, who don’t want to get vaccinated,” he said at a White House press briefing last month.

To be sure, the rollout has been slow going. County websites have been overloaded by people who desperately want to be immunized, and manufacturing isn’t yet fully ramped up. But the one thing that time and money can’t as easily solve is persuading people to take the vaccine.

Some of the vaccines are still sitting on shelves “because of very real vaccine hesitancy that does exist in certain communities,” Loyce Pace, a member of Biden’s now-disbanded transition Covid-19 advisory board, said during a webcast Jan. 14. The Biden administration has to work to get “people to line up for these vaccines when their time comes because we know that will be a critical component to getting on the other side of this crisis,” she added.

Nationally, about 60% of employees at long-term care facilities who were offered the shots through a federal program run by Walgreens and CVS Health declined to get them, according to Rick Gates, the head of pharmacy and health care at Walgreens. Just 20% of the residents turned down the doses, he said Tuesday.

Ina Siler, a patient at Crown Heights Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation, a nursing home facility, receives the Pfizer-BioNTech coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccine from Walgreens pharmacist Annette Marshall, in Brooklyn, New York, December 22, 2020.

Yuki Iwamura | Reuters

In New York City, some 30% of the health-care workers eligible for the vaccine refuse to get it, Mayor Bill de Blasio recently said. “We were expecting a lot of people (would) want to get vaccinated. We were getting 30% or 40% or 50% of those eligible who were passing on it,” de Blasio said at a press conference last week.

Out of the roughly 7 million New Yorkers who are currently eligible across the state — health-care workers and people 65 and older — just 1.7 million people have received their first shots and about 500,000 have gotten their second one, Gov. Andrew Cuomo said Friday. He said he’d give hospitals another week to get all of their workers immunized before he expands eligibility to people under 65 with underlying health conditions.

“Hesitancy is a major obstacle in our path. Hesitancy is a new term for people who don’t want to receive the vaccine,” he said. “They’re skeptical. They’re cynical about the vaccine, and they’re not willing to take it.”

‘We’re in a tough spot’

The reluctance or refusal to be vaccinated has been a growing problem in the U.S. long before the pandemic started. Medical experts point to a long-debunked study published by British researchers in 1998 linking measles vaccines to autism in children. That only emboldened anti-vaxxers, a group of activists known for their opposition to vaccinations and for spreading misinformation about vaccines, physicians and scientists say.

Former President Barack Obama has said the Tuskegee study still lingers as a painful memory that’s led to vaccine skepticism in Black and Brown communities. Researchers who conducted the infamous study from 1932 to 1972 gave Black men with syphilis placebos instead of penicillin so government researchers could study the long-term effects of the disease.

A healthcare worker administers a shot of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine to a woman at a pop-up vaccination site operated by SOMOS Community Care during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in New York, January 29, 2021.

Mike Segar | Reuters

A recent poll of New Yorkers shows significant hesitancy in minority communities, Cuomo said. The poll, conducted by the Association for a Better New York, found that 78% of White residents would take the vaccine as soon as they could compared with 39% of Black residents, 54% of Hispanics and 54% of Asians.

Fear due to the pandemic and misinformation last year from then-President Donald Trump and others about the virus has exacerbated the situation and could hinder the government’s plan to vaccinate the U.S. population, medical experts told CNBC.

“We’re in a tough spot,” said Daniel Salmon, director of the Institute for Vaccine Safety at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “A substantial proportion of the population thinks that Covid isn’t really a big deal and it’s kind of a hoax and the numbers are being, you know, overblown and doctors are making money by diagnosing Covid and calling deaths.”

“I mean, that’s obviously ridiculous. It is not true,” said Salmon, who oversaw the federal vaccine safety monitoring program during H1N1. “But that’s what maybe a third of the population thinks.”

People ‘in the middle’

To gain the public’s trust and boost turnout, some states and cities have been launching outreach campaigns on vaccines. In California, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that the state was rolling out a public awareness campaign in more than a dozen languages. Health-care workers are also trying to build public confidence, often posting photos of themselves getting shots on social media.

Gov. Gavin Newsom watches as the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine is prepared by Director of Inpatient Pharmacy David Cheng at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, U.S. December 14, 2020.

Jae C. Hong | Reuters

Federal and state health agencies need a concerted effort to educate communities, particularly those who are hesitant but can still be persuaded to take the vaccine, Salmon said.

“Roughly half the people want to take the vaccine, and about 10% don’t want it,” Salmon said. “That 10% is going to be really hard to change their mind. And what you’re left with is 40% that are somewhere in the middle.”

John Ou, a former Wall Street bond trader who now owns a food truck in Los Angeles, is one of those people.

Ou said he has some concerns about the vaccine but probably would still get a shot if a physician offered him one on the street. He said his main concern is the speed with which the vaccines were developed.

Pfizer announced its plans to develop a coronavirus vaccine with BioNTech in March. They submitted their application to the Food and Drug Administration in November and were granted emergency authorization a few weeks later. It was a record-breaking time frame for a process that normally takes years. The fastest-ever vaccine development, for mumps, took more than four years and was licensed in 1967.

“Like everyone else, I’d like to see a few people take it first before I get in line to get it,” Ou, 51, told CNBC in a phone interview. “I’ve never been a first adopter. Like when Apple comes out with a new iOS or iPhone, I’m always going to wait a few months to see what the problems are, because there are always problems.”

‘I’m not in a rush’

Victor Aponte, a contractor in his 50s who lives in New York City, is also on the fence.

Like Ou, he has concerns about how quickly the vaccines were developed. He also said he’s skeptical whether the vaccines will work, considering scientists are discovering new variants of the virus that may make the vaccines less potent.

Moderna announced on Jan. 25 that it is accelerating work on a Covid-19 booster shot to guard against the recently discovered variant in South Africa. Later that same week, Pfizer said that it was also developing a booster to protect against Covid-19 variants.

Aponte said he’s not in a rush to get the vaccine.

“I really want to see where this goes, because as fast as they push these vaccines out and there are millions of shipments is right when they let us know this thing is mutating,” he said. “I have to be protected. But I don’t want to take something that’s going to be useless and potentially causes me harm.”

Even with the vaccine, he thinks the pandemic will get worse before it gets better.

“In this country alone, we won’t be fully vaccinated for another two years,” he said. “We’re not out of the woods because people think the vaccine is some kind of superhero. No, we still have a lot who think this is a hoax.”

Rebuild trust in vaccines

As part of Biden’s sweeping plan to end the pandemic, the administration has said it plans to launch a public information campaign to rebuild trust in the vaccines. “We’ll help people understand what science tells us. That the vaccines help reduce the risk of Covid infections and can better safeguard our health and the health of our families and our communities,” Biden said in a speech before he was sworn into office in January.

President Joe Biden visits a coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccination site during a visit to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, Jan. 29, 2021.

Kevin Lemarque | Reuters

Many medical experts had criticized the Trump administration’s messaging on vaccine development, including calling its coronavirus vaccine project “Operation Warp Speed.” The language, they said, doesn’t make it clear that officials are not cutting corners but rather are accelerating the development of vaccine candidates by investing in multiple stages of research at once.

The language the Trump administration used has been “awful,” said Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who is also a member of the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee.

“Operation Warp Speed, race, finalists. I mean it sounds like the Miss America pageant or something. It’s frightening. The language is frightening,” he said. White House press secretary Jen Psaki said the name of the program under Trump will be retired.

Black and Brown communities

Jonathan Jackson, director of the Massachusetts General Hospital’s CARE Research Center, which works with communities to improve representation in clinical trials, said the government efforts should include focusing on Black, Latino and Indigenous people as well as people in rural areas who may lack access to health care.

“It just seems like yet another case where vulnerable folks are being left behind. And I think that is really what is driving vaccine hesitancy this time around rather than some long-debunked science,” he said, adding that it wasn’t a priority during the Trump administration. “So that means our playbook has changed and we need to have a different approach.”

While there are people in the community who are fiercely opposed to the vaccine, there are others who are “on the margins” and could be persuaded, he said.

“We’re not talking to suburban, stay-at-home moms. We’re talking to folks who know folks who have been infected or ignored or abused by these same systems. We have to address that before we can expect widespread adoption of vaccines,” Jackson said.

Protesters demanding Florida businesses and government reopen, march in downtown Orlando, Fla., Friday, April 17, 2020. Small-government groups, supporters of President Donald Trump, anti-vaccine advocates, gun rights backers and supporters of right-wing causes have united behind a deep suspicion of efforts to shut down daily life to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

John Raoux | AP

Conspiracy theories

Some people will never be convinced the vaccine is safe, no matter what the new administration does, Offit said.

Those are the “conspiracy theorists,” he said. “That is a person who is not going to believe the data no matter what you tell them. They think pharmaceutical companies have the government in their pocket … they are not going to believe anything you tell them.”

Conspiracy theories run amok and are getting big audiences on Twitter and Facebook. One of them postulates that billionaire tech mogul and philanthropist Bill Gates wants to use coronavirus vaccines to implant tracking devices in billions of people. Another conspiracy theory says the Covid-19 vaccines change people’s DNA. Neither theory is true, leading scientists say.

On Oct. 13, Facebook said it was launching a new global policy that bans ads that discourage people from getting vaccines, though it will still allow ads that advocate for or against legislation of government policies around vaccines, including a Covid-19 vaccine.

Offit said most people aren’t conspiracy theorists. It will be up to public health officials and drugmakers to be transparent about what they know about the vaccine, including what they don’t know and any long-term effects, he said.