In his first address since taking up the top post in January, Jakob Stausholm said he would strive to restore trust in the company, shattered after it destroyed a sacred Aboriginal site to make way for an iron ore mine expansion in Western Australia.

The blasts at Juukan Gorge cost former CEO Jean-Sébastien Jacques and two other senior executives their jobs as investors and indigenous groups demanded accountability for the incident.

Rio’s new leader promised on Wednesday to work with traditional owners as the company continues to grow its flagship iron ore division.

Stausholm comments were made in the context of Rio’s publication of its 2020 results. Underlying earnings rose 20% to $12.4 billion in the period. Net debt fell to $664 million from $3.65 billion. Profit before tax was $15.4 billion, up from $11.1 billion in 2019.

Stausholm said 2020 was an “extraordinary year” for Rio but also one “of extremes”.

“Our successful response to the COVID-19 pandemic and strong safety performance were overshadowed by the tragic events at the Juukan Gorge, which should never have happened,” he said.

Emissions U-Turn

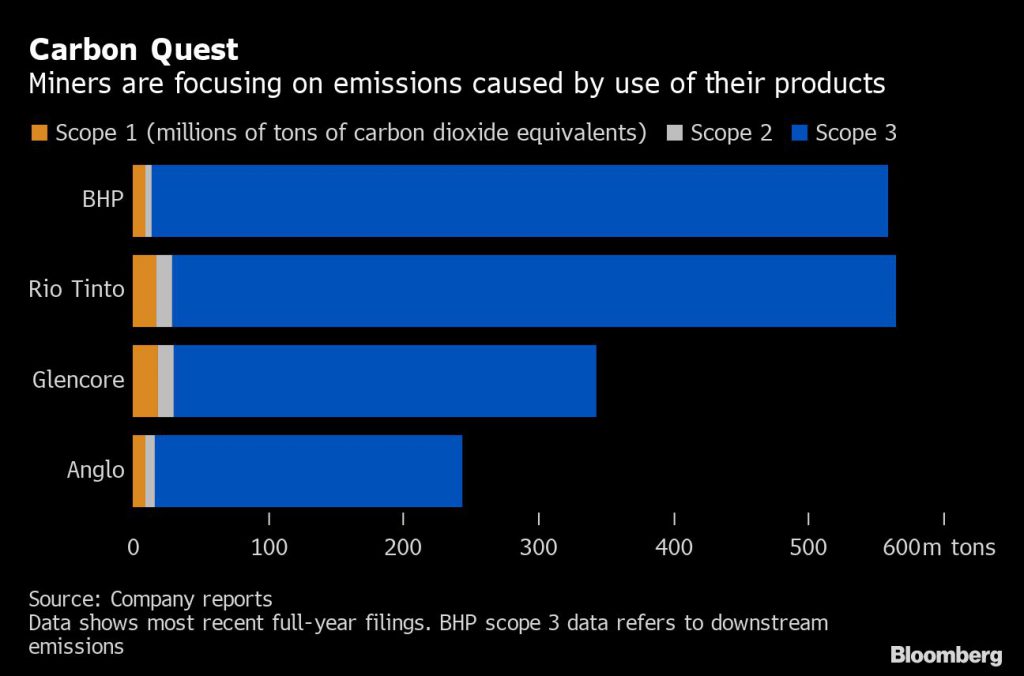

Stausholm also announced that the group is reversing an earlier stance on Scope 3 — those generated by customers through the use of its products — by owning its role in how third parties use the commodities it mines.

Rio Tinto is also the world’s top iron ore miner, a commodity responsible for around 85% of its profits. Given its huge exposure to the steel industry, one of the world’s heaviest polluters, the company has come under increasing pressure to help making steelmaking a more environmentally-friendly activity.

The process of producing steel involves adding coking coal to iron ore to make the alloy and is responsible for up to 9% of global greenhouse emissions.

“Today, you should just see it as an extension, recognizing that we can actually work together with our partners to reduce the Scope 3 emissions”

Rio Tinto’s CEO Jakob Stausholm

The mining giant vowed in 2020 to spend $1 billion over five years. The ultimate goal was to have “net zero” greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Rio also said at the time that its total Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions (indirect emissions from the generation of purchased energy consumed by a company, such as electricity) would be 15% lower by 2030 than 2018 levels.

The company, however, did not set a target to reduce scope 3 emissions, arguing it was nearly impossible to control how steelmakers use the iron ore it provides them.

Rio said on Wednesday it will now work with customers to reduce steelmaking carbon intensity by at least 30% from 2030. It is also aiming for carbon-neutral steelmaking and zero-carbon aluminum and net-zero emissions from shipping by 2050.

Taking a page from rival BHP’s (ASX, LON, NYSE: BHP) book, Rio said it will tie executive bonuses to progress.

“We are all learning on the journey of climate change,” Stausholm said on Wednesday. “Today, you should just see it as an extension, recognizing that we can actually work together with our partners to reduce the Scope 3. It is a real shift, but it’s also a natural development. You start with your own emissions, and then you expand from there.”

A study published last year showed that eight of the world’s top ten largest mining companies were not doing enough to help keep global temperatures from increasing by less than 2°C a year by 2050.