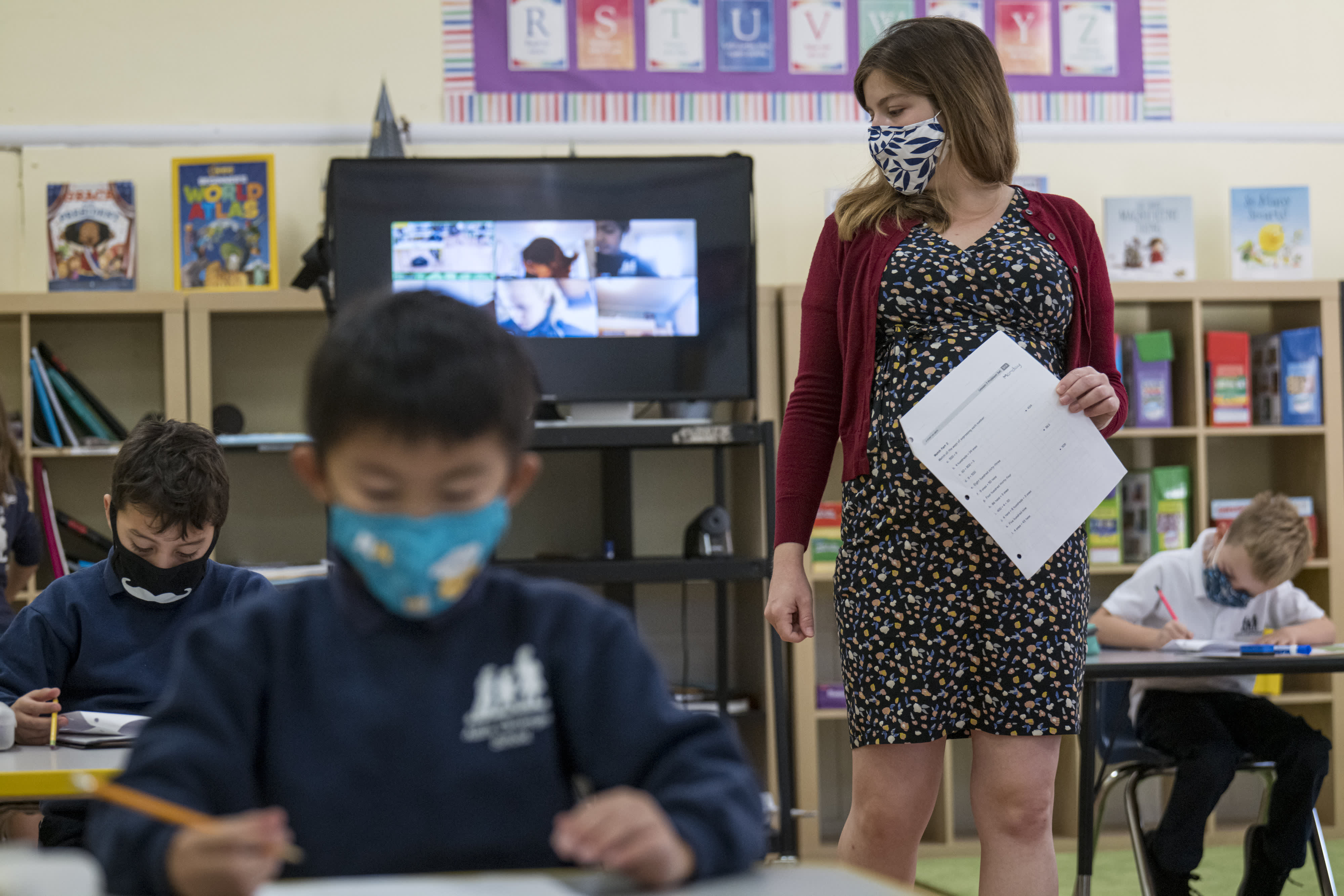

The challenges of teaching in-person or online have stretched educators to their limits.

After nearly a full year of either putting themselves at risk in a classroom or struggling to reach students remotely, many now say they may change careers or simply quit.

“Teachers have been feeling the brunt of how drastically this pandemic has changed our world,” said Colin Sharkey, executive director of the Association of American Educators, a national professional association.

“The demands that are put on them are off the charts.”

At a time when many state and local governments are struggling to recruit and retain educators, a nationwide poll of public education professionals found a growing number are ready to leave their jobs.

More from Personal Finance:

Teachers are next in line for the Covid vaccine

Many schools struggle to reopen for in-person learning

Biden rolls out his plan to reopen schools

Overall, K-12 employees’ general satisfaction with their employers sank to 44% in October from 69% in March 2020, according to a report from the Center for State and Local Government Excellence. Of the roughly 3.5 million full- and part-time public school teachers, more than one-third, or 38%, said that working during the pandemic has made them consider changing jobs.

At the college level, even more — about 55% — of faculty have seriously considered changing careers or retiring early, according to a separate report from Fidelity Investments and The Chronicle of Higher Education.

The last 11 months have taken an emotional toll on teachers across the board, the report found. Yet, women, in particular, were more likely to feel overworked and overwhelmed as a result of the pandemic, in part, because they are also more likely to manage additional childcare responsibilities at home.

The pandemic has pushed many faculty members to the verge of burnout.

Debra Frey

head of tax-exempt marketing and analytics at Fidelity Investments

“The pandemic has pushed many faculty members to the verge of burnout,” said Debra Frey, head of tax-exempt marketing and analytics at Fidelity Investments.

“They’ve been asked to adapt to an uncertain and constantly changing work environment over the past year, while also dealing with personal challenges brought on by Covid,” she said.

“This has left many feeling overworked, fatigued and wondering if they even want to continue to be an educator.”

Roughly three-quarters, or 77%, of educators are working more today than a year ago, 60% enjoy their job less and 59% do not feel secure in their school’s health and safety precautions, according to another report by Horace Mann.

Yet, those who are considering retiring early may not be financially ready to do so. Although 403(b) account balances — the most common type of retirement plan for educators — have been on the rise, the average total was just $106,000 at the end of 2020, according to Fidelity.

Further, over the last year, many schools cut contributions to these employee retirement plans to reduce costs in the face of budget shortfalls.

At the same time, long-standing compensation policies, which include fixed pay and pensions for tenured faculty, have made it harder for schools to attract young talent or redirect funds toward technology upgrades or financial aid in response to the current crisis.

“The labor dynamics that have dictated education over the last 50 years prioritized long-term contracts,” Sharkey said. “This isn’t best serving our educators or our students.”

Of course, as the Covid crisis drags on, there is a need for more teachers, not fewer.

“Every school needs funding — gobs and gobs of funding — right now to pay for teachers,” said Joel Hall, an English teacher at Forest Lake High School in Forest Lake, Minnesota. “There are not enough to go around.”

Before schools can fully reopen, institutions must first address crowded classrooms and a shortage of available staff.

Yet breaking up large classes into smaller groups requires hiring even more full- or part-time teachers, Hall said.

“Classes of 35 have never been what’s best for kids, which wouldn’t be an issue if we had the money to pay for another math teacher,” he added.

Fidelity polled more than 1,100 faculty at two- and four-year colleges and universities across the country in October. Of these, 48% were tenured faculty, 11% were tenure-track, 16% were non-tenured, and 25% were part-time or adjunct.

The Center for State and Local Government Excellence surveyed more than 1,200 state and local government employees, including nearly 500 K-12 public school employees also in October.