Former WaMu CEO sees a housing bubble forming because the Fed is ‘hooked on’ low interest rates

Like many other banks, Washington Mutual rode the wave of low-interest rates to grow its mortgage business during the housing boom of the early 2000s. During Kerry Killinger’s time as CEO, WaMu grew to have more than $300 billion in assets.

But when the subprime bubble burst, the bank’s fortunes quickly turned. In September 2008, at the height of the financial crisis, Killinger was forced out by the company’s board, and ultimately the bank was seized by federal regulators. It still stands as the largest bank failure in U.S. history.

In their new book, “Nothing Is Too Big to Fail: How the Last Financial Crisis Informs Today,” Kerry Killinger and his wife Linda, who previously served as the vice chair of the Federal Home Loan Bank of Des Moines, explore WaMu’s failure, the government’s response to the last crisis and where there is growing risk in today’s economy.

“ The failure of Washington Mutual still ranks as the largest for any bank in U.S. history. ”

The couple argues that federal regulators erred in how they treated Washington Mutual and other so-called thrifts, or savings and loan associations, which specialized in savings deposits and consumer lending.

“There were plenty of mistakes to go around for everybody in the last financial crisis,” Kerry Killinger told MarketWatch. “And I think some of the mistakes were made on the part of the government regulators — they had no game plan for dealing with the crisis.”

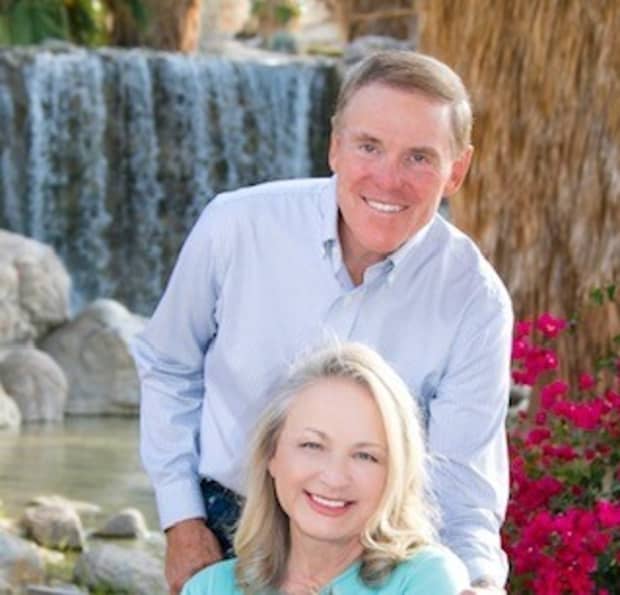

Kerry and Linda Killinger have authored a new book examining the causes of the last financial crisis and how current policies could be creating risk in the economy.

Courtesy of Kerry and Linda Killinger

In the book, the Killingers raise concerns about asset bubbles they believe are forming in a wide range of asset classes, including stocks, art and luxury items — and housing. MarketWatch spoke with Kerry and Linda Killinger about the book, the Federal Reserve and how to avoid another global financial crisis like the 2008 meltdown.

MarketWatch: In your book’s introduction, you seem to argue that other books that examined what transpired in the last financial crisis gloss over some of the factors that caused the meltdown. How is your perspective different from other books on this subject?

Linda Killinger: I wanted to write a book about this because it was such an unusual, crazy experience. Back in the ’80s I was a partner in an international accounting firm, and the regulators would call me in to do plans for banks that were failing in that time. I noticed that the regulators would do everything they could to help a bank get liquidity, or to help save a bank that had not been consumed in crime or problems. But in this crisis of 2008, it just seemed like nobody wanted to help community banks. In fact, they just did the opposite. They really went after them. I thought it was important to write about the difference and how important it is to help community banks in a crisis like this.

Kerry Killinger: My focus was more on public policy — about being sure we learned all the lessons we possibly can. I’ve become very concerned that some of the policies currently being adopted by the Federal Reserve and the regulators in government may be leading us to a new financial crisis.

“ ‘Some of the policies currently being adopted by the Federal Reserve and the regulators in government may be leading us to a new financial crisis.’ ”

MW: In your book, you explain that you see another bubble forming in residential real-estate — just one of the many asset bubbles you warn about. What do you believe caused the last housing bubble that led to the Great Recession and how does it compare to what’s going on now?

Kerry Killinger: We’ve lived through a lot of housing cycles in our careers, and including the big bubble that that was created in the early 2000s. The housing bubble was primarily caused in the early 2000s by the Fed keeping the fed funds rate below the rate of inflation for several years. They did that in 2000 through 2003, and that lowered mortgage payments so low and led to housing prices increasing because housing affordability was good with very low mortgage payments. That caused housing prices to rise much more quickly than the rate of inflation.

From 2000 to 2006 nationally housing prices rose about 83%. Over that same period, the rate of inflation was up about 20%. So a huge increase faster than the rate of inflation, and over the long run, housing prices ought to rise at about the rate of inflation, which was about 2% a year or so. Clearly it was a speculative period where prices were rising too quickly, and speculators and investors increasingly jumped on board.

To help fuel it, underwriting standards were reduced by Fannie and Freddie, the FHA, VA, Wall Street, bank portfolio lenders, and all that. Then on top of that we had this growth of subprime lending. Keeping rates so low for so long was the most important driving force in my opinion.

[Today] the similarities are that the Fed has pursued this policy of ultra-low interest rates with the fed funds rates. Increasingly, the Fed is keeping mortgage rates at an artificially low level for 30-year fixed rates by purchasing assets in their own portfolio, including mortgage-backed securities and an increasing array of guarantees that the Fed has done as part of its policies to fight an economic downturn.Those actions have led to what I’m calling ultra-low mortgage payments, and that naturally led to a surge in housing prices. Since 2015 housing prices nationally were up about 36% — more than three times the rate of inflation over that period.

Another similarity is we’re seeing speculators and investors jumping in. This go-around it’s large entities wanting to buy tracts of homes to use as rental housing. So the non-owner-occupied part of the market, which is the investor side, has gone up from 31.9% to 34.4% in the past year. We’re getting a repeat of speculation coming in at this stage with investors coming in in a major way.

Now, subprime lending is not the same factor it was the last go-around fortunately, but we do know that there’s an increasing amount of subprime lending going on by the FHA, VA and some of the government enterprises. On the good news side, I think underwriting standards have remained better, much better, than they were in the last go-around. But my caution is underwriting standards are all based on housing prices that are, I believe, inflated because of these ultra-low-interest mortgage rates.

MW: You wrote about how, in your view, the Fed’s response last time around exacerbated the financial crisis. And just now, you spoke about how the Fed is contributing to the rise in home prices. So what role do you think the Fed should play in addressing the bubble that you argue is forming now?

Kerry Killinger: This go around I think the Fed has learned that it needs to provide plenty of liquidity to keep from having a crisis. My concern is I think the Fed has gotten hooked on these expansive policies of ultra-low interest rates, asset guarantees, asset purchases and flooding the system with liquidity for a long period of time. And those policies are very appropriate for helping get an economy out of a recession in order to get things stabilized, but their use over extended periods of time always leads to an escalation in inflation and the creation of asset bubbles.

“ ‘The Fed has gotten hooked on these expansive policies of ultra-low interest rates, asset guarantees, asset purchases and flooding the system with liquidity for a long period of time.’ ”

They are caught in a conundrum now. The policies that were appropriate to help get us beyond COVID-19 — the longer they keep using those same policies, I think they just keep inflating these bubbles. And it will be very difficult to manage them down in an orderly manner. All assets go through these kinds of ups and downs — the key is how do we manage them in a way that doesn’t cause immediate implosion, like they did in 2008? The longer they allow these bubbles to keep growing, the bigger challenge they’re going to have at some point in the future.

MW: You’re both strong proponents of community banks and have argued that they should play an important role in the mortgage industry. But following the Great Recession, many banks have reduced or eliminated their mortgage businesses, citing the steep cost of regulation, and non-bank mortgage companies have risen up to fill that void. Should the federal government make it easier for community banks to lend mortgages, and how should it go about doing so?

Linda Killinger: Well, it depends. I think, if it looks like a bank, it smells like a bank and does mortgages like a bank, it should be regulated like a bank. Unless there’s some incredible service that they provide that banks don’t provide — otherwise, they’re doing the same thing as community banks but they’re not being regulated.

The problem with that is things are going pretty well right now because they’re selling mostly to Fannie and Freddie. Fannie and Freddie’s guidelines are pretty good right now, but at any point in time [non-banks] could couple up with unregulated hedge funds or other entities from Wall Street and start securitizing loans themselves, lowering standards and trying to attract more people.

Especially if the Congress and the new president want to have more affordable housing, it depends on what they do when they want to push for more. There needs to be more affordable housing, but it shouldn’t be handled in the way that it was last time. Last time they had Fannie Mae in the 90s saying well 33% of your loan should be [low- and middle-income (LMI)] loans, and by 2008 it was 60% should be LMI. So there’s a tremendous pressure on Fannie and Freddie from Congress and the other regulators to really crank out more LMI lending. We really have to be careful about how we do that in the future. Community banks should be involved because they know how to do it right.

“ ‘If it looks like a bank, it smells like a bank and does mortgages like a bank, it should be regulated like a bank.’ ”

MW: When the COVID-19 pandemic began, federal lawmakers and regulators were quick to roll out forbearance options to homeowners who suddenly lost income as a result of the economic shock. A year later, many homeowners are still not making their monthly mortgage payments and are in forbearance. With the foreclosure moratorium still in place, homeowners aren’t yet at risk of losing their homes, but that possibility lingers. What should we be doing right now to stave off another foreclosure crisis?

Linda Killinger: During the crisis in 2007, when it started to collapse, Kerry put together a $3 billion fund [at WaMu] to help subprime borrowers stay in their homes. He lowered the payments, and he lowered the amount that was owed, so it was manageable and they could stay in their home. I think that’s a responsibility of banks to do that. It’s going to be hard when the forbearance goes away — unless banks and organizations are willing to really write down the principal or lower the payments just to help people a little bit more.

Kerry Killinger: Over the long run you are far better off to do everything you can to keep somebody in a home, if they can possibly afford it. And the last route you want to have to go through is foreclosure, because the costs are painful for everybody involved. We always used to try to do anything possible to keep people into the homes as long as we possibly can, and I think that is a very positive thing what the government and everyone did when COVID hit. Some of those solutions are very appropriate for the short term when you’ve got a crisis going on, but I think over time they need to be brought back to a more normal environment in which you will always have a small percentage of homes that will have to go through foreclosure. They were just the wrong home for the wrong people at the wrong time.

People don’t even think about that anymore, but home prices will fall again in some markets for some reason. Given the rapid escalation we have seen in the last five years, especially in the last 12 months, these are unsustainable price increases that will be subject to some kind of correction when interest rates start to return to more normal levels. Probably one of the more controversial things I’ll say here is if you assume that we’re going to have about a 2% inflation rate and a GDP growing over the long term at about 2% to 2.5%, then mortgage interest rates on 30-year fixed-rate mortgages should be more in the 4.5% to 5% range.

MW: Do you think consumers are willing to stomach mortgage rates at that level, after so many years in which mortgage rates have remained so low?

Kerry Killinger: Look, all of us want to have the good times roll. Everybody wants to have asset prices forever going up and the cost of financing to be next to nothing. That’s something that a lot of people wish for. We’re just putting the warnings out that seldom do things go up forever. Right now you have borrowing costs substantially below the rate of inflation and way below historic norms, and that’s unlikely to last forever.

I don’t know if it’s a matter of whether the consumers like it or not, but equilibrium would be closer to 4.5% to 5% on long-term mortgages. I just put out there that if that happens, for whatever reason, the affordability of housing will become much more stressed and mortgage payments will grow. That will have a tendency to put downward pressure on home prices. I don’t think we’re likely to repeat the problems that hit in 2008 because I think the Fed is smart enough now not to pull liquidity to a point that causes a downward spiral. But you could certainly see a period over several years of some downward pressure on prices as affordability becomes more difficult because of rising monthly mortgage payments.

“ ‘Right now you have borrowing costs substantially below the rate of inflation and way below historic norms, and that’s unlikely to last forever.’ ”

MW: What else about the market and the economy right now is a source of concern to you?

Kerry Killinger: I do think that the economy is both stabilized and now back into a strong growth mode, and I think we’re going to see very strong economic activity for the balance of this year and into next year. Inflation is picking up and will be higher than what many think at this point. Businesses are telling me that they are having more price increases today than they have had in the last decade. So I think the concern about inflation is real.

And these growing asset bubbles just continue to escalate to the point to where the assets are selling well above reasonable estimates of intrinsic value. That always presents a certain amount of risk. And finally, we’re seeing more and more speculative products and speculators in the market — not necessarily just in housing.

Look at certain parts of the stock market DJIA,

Linda Killinger: Yes, and are pension plans buying some of those bubble products?

Kerry Killinger: A fair bit of that build-up of buyers for those single-family homes are pension plans doing it directly to have that asset category. Because with the Fed keeping interest rates artificially low, they can’t afford to put into riskless assets like Treasury securities. They have to keep searching out yields. One of them is increasingly into residential real estate.

(This interview was edited for clarity and length.)