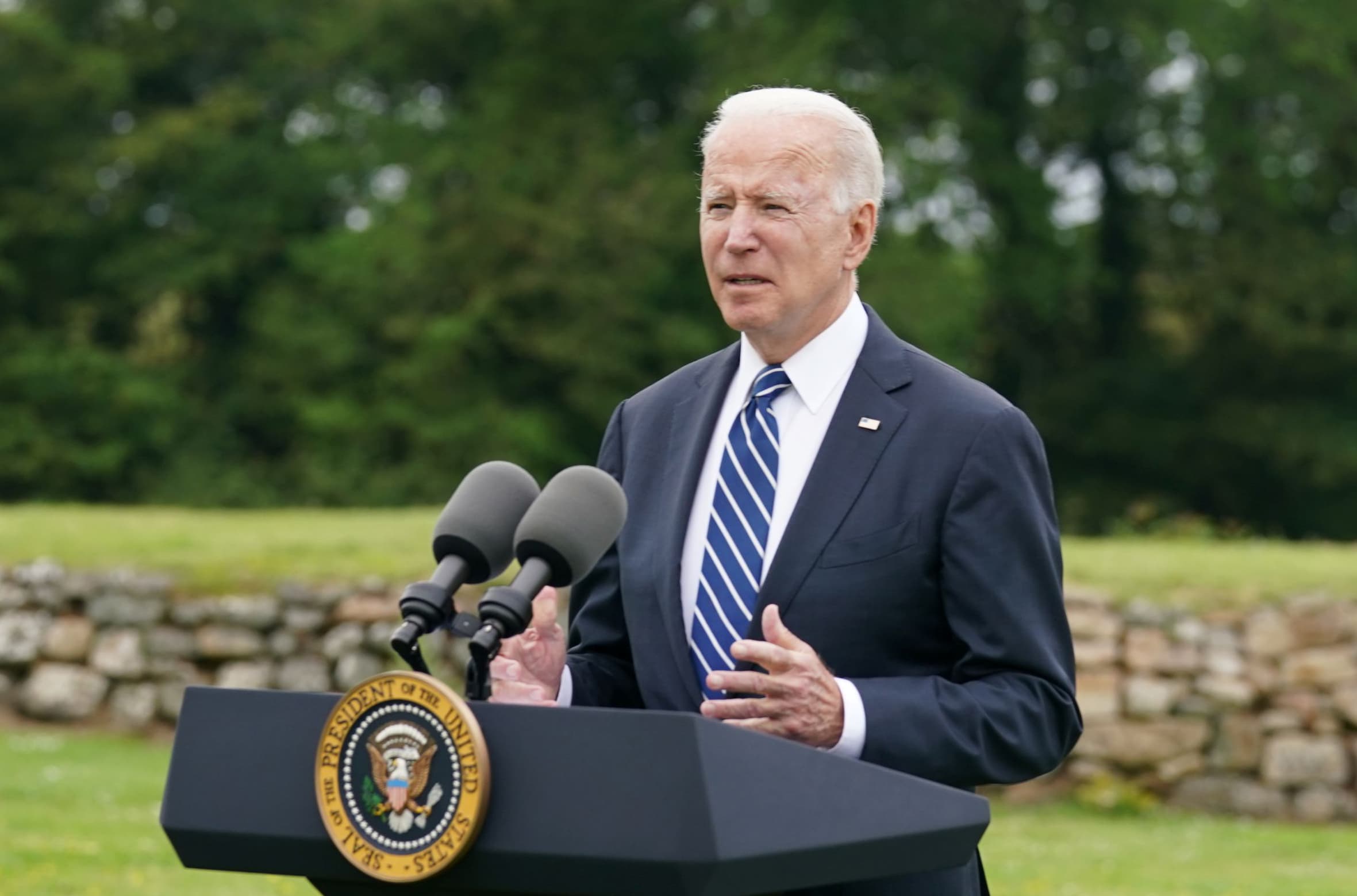

U.S. President Joe Biden speaks about his administration’s pledge to donate 500 million doses of the Pfizer (PFE.N) coronavirus vaccine to the world’s poorest countries, during a visit to St. Ives in Cornwall, Britain, June 10, 2021.

Kevin Lemarque | Reuters

WASHINGTON — President Joe Biden and leaders of the G-7 group of nations will publicly endorse a global minimum corporate tax of at least 15% on Friday, one piece of a broader agreement to update international tax laws for a globalized, digital economy.

The leaders will also announce a plan to replace Digital Services Taxes, which targeted the biggest American tech companies, with a new tax plan linked to the places where multinationals are actually doing business, rather than where they are headquartered.

For the Biden administration, the Global Minimum Tax plan represents a concrete step towards its goal of creating what it calls a “foreign policy for the middle class.”

This strategy aims to ensure that globalization and trade are harnessed for the benefit of working Americans, and not merely for billionaires and multinational corporations.

For the rest of the world, the GMT is intended to end the tax cutting arms race that has led some countries to cut their corporate taxes much lower than others, in order to attract multinational companies.

If widely enacted, the GMT would effectively end the practice of global corporations seeking out low-tax jurisdictions like Ireland and the British Virgin Islands to move their headquarters to, even though their customers, operations and executives are located elsewhere.

The second major initiative Biden and G-7 leaders will announce Friday is a plan they are “actively considering” to expand the International Monetary Fund’s supply of Special Drawing Rights, an internal IMF currency, that are available to low-income countries.

This plan is aimed at expanding international development financing to poor countries and helping them to purchase Covid vaccines and recover more quickly from the pandemic’s effects, according to a White House fact sheet.

The White House also said G-7 leaders will agree to “continue providing policy support to the global economy for as long as necessary to create a strong, balanced, and inclusive economic recovery.”

But it is the GMT plan that has the greatest potential to impact corporate bottom lines and influence investor decisions.

The G-7 tax agreement “will serve as a springboard to getting broader agreement at the G-20,” said a senior administration official, who spoke to reporters on background in order to discuss ongoing talks.

A joint statement issued Thursday by Biden and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson offers a preview of what to expect from the global tax agreement between the G-7 partner nations.

Britain’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson speaks with U.S. President Joe Biden during their meeting, ahead of the G7 summit, at Carbis Bay, Cornwall, Britain June 10, 2021.

Toby Melville | Reuters

“We commit to reaching an equitable solution on the allocation of taxing rights, with market countries awarded taxing rights on at least 20% of profit exceeding a 10% margin for the largest and most profitable multinational enterprises,” the statement says.

“We also commit to a global minimum tax of at least 15% on a country by country basis.”

As part of this agreement, “we will provide for … the removal of all Digital Services Taxes, and other relevant similar measures, on all companies.”

The removal of Digital Services Taxes, a patchwork of country-by-country taxes that specifically target the biggest American tech companies, represents a real victory for the United States.

Analysts say the removal of these taxes — and an end to the looming threat of new DSTs — would add a level of certainty to the international tax system that would ultimately benefit Big Tech companies in the long term, even if a new Global Minimum Tax raised costs in the near term.

Once the G-7 leaders adopt the GMT proposal, the next step will be to win support for it among the G-20 nations, a diverse group of economies that includes China, India, Brazil and Russia.

G-20 finance ministers and central bank governors are scheduled to meet in Venice, Italy, in July. The IMF funding proposal and the international tax plan are both expected to be high on the agenda.

It’s unclear at this point whether the GMT plan will win the support of the 19 member nations and the European Union.

Details of the plan have yet to be hammered out, and some of the G-20 countries keep corporate tax rates relatively low in an effort to lure businesses.

Much of the groundwork for adopting a GMT has already been laid by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or OECD, which released a blueprint last fall outlining the two-pillar approach to international taxation.

The OECD Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, known as BEPS, is the product of negotiations with 137 member countries and jurisdictions.

One pillar is the plan for countries to collect taxes from multinational corporations based on the share of that company’s profits derived from a particular country’s consumers.

The second pillar is the global minimum corporate tax, a set rate of at least 15% that would apply even when tax rates in a particular country are lower than that.