How a gold-stibnite restoration in Idaho could add antimony to US supply chain

The results of an independent feasibility study released last year envision the project becoming one of the largest and highest-grade open-pit gold mines in the United States with over 4 million ounces of gold in reserve —and the country’s only primary producer of antimony, a critical and strategic mineral.

There is currently no domestic antimony source, and 90% of world supply is controlled by China, Russia and Uzbekistan, a narrative becoming increasingly untenable when it comes to sourcing minerals crucial to North America’s supply chain.

“[Antimony] deserves much more credit than it gets – ultimately it’s the unsung hero,” Mckinsey Lyon, VP, External Affairs, Perpetua Resources, told MINING.COM.

“Right now it is essential in energy technology, whether it’s the glass clarifying component in solar panels, or in the metal-strengthening component in bearings of wind turbines and hydro turbines — it’s also used in large capacity storage batteries.”

“It’s a missing piece in a renewable grid. You have to be able to store that energy, and the technology that’s focusing on antimony as its core is liquid metal battery,” she said.

“The really great economic leap forward has to do with mass storage devices which mesh with energy grids to provide off-peak storage of electricity”

Hallgarten & Company

Perpetua Resources has signed an agreement with US Antimony to explore the potential of processing antimony from stibnite at US Antimony facilities.

US Antimony, which received a $510,500 grant from the US Department of Defense, has the only primary antimony processing facilities in North America and the Stibnite Gold project is poised to be the only US source of mined antimony.

According to Perpetua’s FS, the project has a total measured and indicated resource of 104.5 million metric tonnes with 1.42 g/t, antimony and 1.63g/t gold. This resource is based on a gold price of $1,250/troy ounce. The expected annual average gold production is 466,000 ounces during the first four years of operations.

Hallgarten & Company published a whitepaper that positions antimony as the “new metal in mass storage”.

“Most of the buzz in the mainstream media is about battery options that extend the life of cellphones or laptops and other PDAs or with regard to hybrid or electric vehicles. However, the really great economic leap forward has to do with mass storage devices which mesh with energy grids to provide off-peak storage of electricity,” the report reads.

Antimony mined from Perpetua’s Stibnite Gold project would be the only domestic supply — 35% of the domestic need for six years of production.

A rich mining history

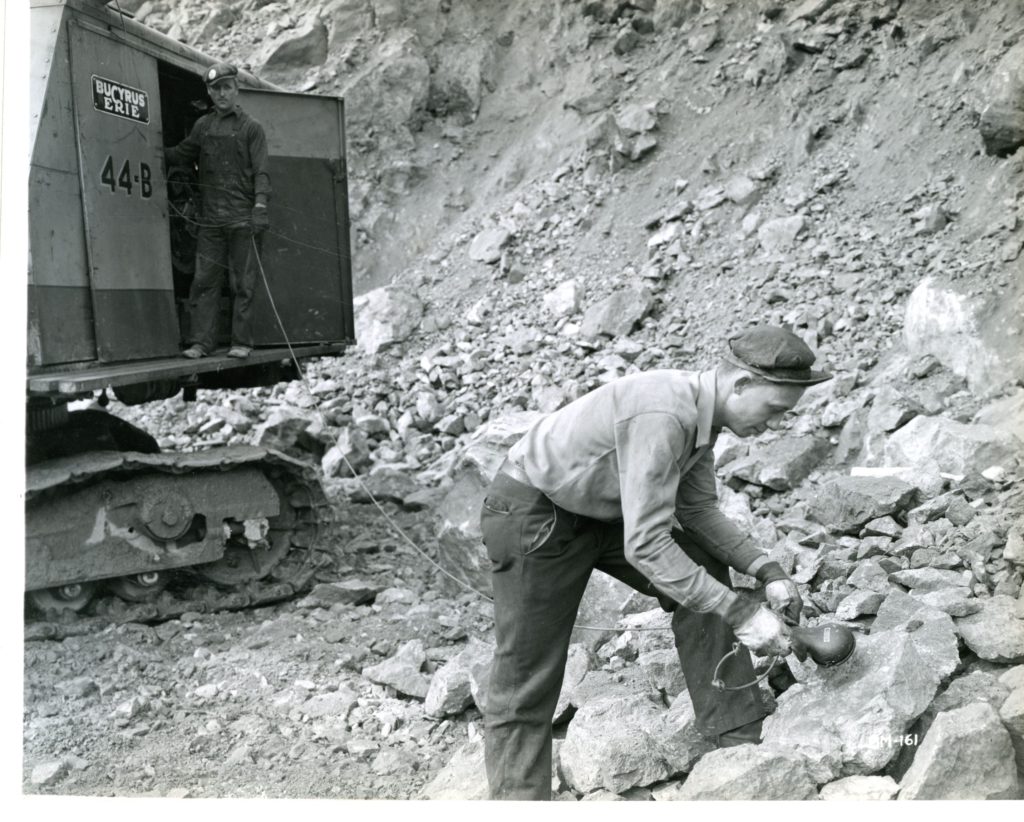

The stibnite mining district in Idaho has been mined since 1899, first for silver and gold as part of Thunder Mountain gold rush.

Almost overnight, what was a very small operation turned into a town of 1,000 people. A whole community developed around production for the war. In the 1940s and 50s, a blockade in the pacific cut off the US’ supply of tungsten and antimony, which were all sourced from Asia.

During that time it was critical for ammunition, and as a primer in paint for battleships and aircraft. Antimony is one of the reasons that the United States government, and entities during World War 2 and the Korean War aligned at Perpetua’s current project location.

“With the blockade of the Pacific, on the eve of WW2, we no longer have a source of tungsten and antimony – so the US government sets out to find it, and they find it in Stibnite, Idaho,” Lyon said.

“The US government then commissioned the small mining operations there – in particular the Bradley Mining Company to produce tungsten and antimony for the war effort.”

Mining continued apace throughout the end of the Korean War, in a manner prior to onset of more stringent environmental regulations.

By the 1990s, after mining for gold and stibnite, the site was left a mess.

A sustainable ESG plan

Perpetua has submitted a plan of restoration and operation to the US Forest Service for review, including restoration of legacy impacts — starting in year one of construction. The 2020 FS confirmed economic benefit to Idaho communities, bringing $1.3 billion in initial capital investment and creating 550 direct jobs.

In August 2020, the US Forest Service published a draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS).

Of the 10,000 comments received, 85% were in support of the project. Lyon said Perpetua reviewed and submitted refinements, and the EIS from Forest Service is expected later this year.

“We understand the importance of this project to Idaho, and that Idahoans are in charge, and leading the way,” Lyon said.

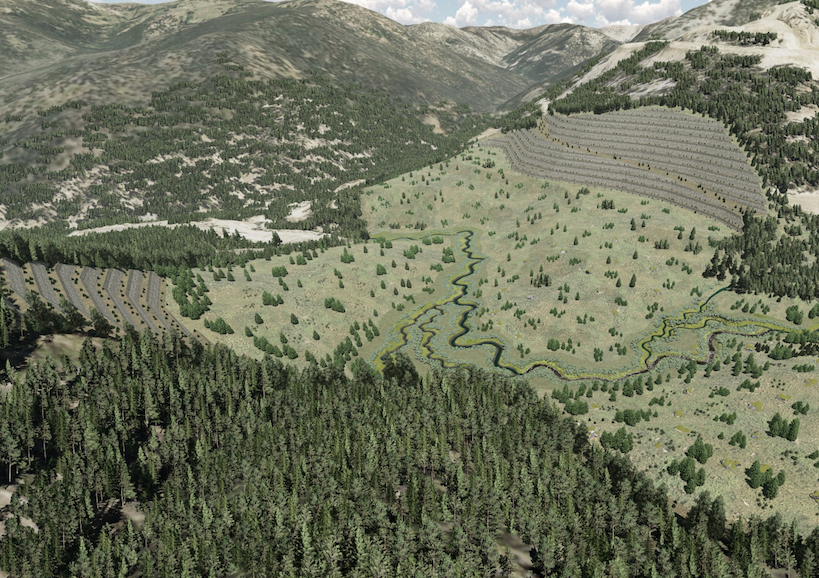

A significant environmental remediation needed is where the south fork of a salmon river flows into an abandoned mining pit on site, where Chinook salmon and Bull trout migrate up the river – meaning miles of critical habitat.

With fish out of natural habitat in a degraded area, and 10.5 million tonnes of legacy tailings affecting water quality, the Perpetua team has their work cut out for them.

“When we got to Stibnite, it was very clear from day one, that if we were going to have a modern mining operation for gold and antimony, we were going to have to pair with it the environmental solutions that were needed,” Lyon said.

“Our project has been designed, in the first years of construction, [that] we go in and fix that source of sedimentation that is degrading habitat and water quality, we pick up the legacy tailings, reprocess and safely store them, and get them out of interaction with ground and surface water.”

Perpetua’s plan is to improve water quality and build a fish passage tunnel.

“We’re going to re-mine the alpine pit — that’s the largest source of gold, and re-route the river into a re-designed fish passageway based on scientific knowledge of the fish migration route… to ensure the adults can getup the river, and the juveniles can get down,” Lyon said.

“It’s fully incumbent of getting those migrating species of fish back to the critical habitat they are blocked from when mining starts. We’re not waiting until the end to get them to their critical habitat.”

Stibnite river restoration will add seven to 11 additional miles to the fish migration route from habitat they are blocked from, Lyon said.

“We can bring the resources, the technology and the expertise to solve a problem that has existed for a really long time.”

The draft EIS indicated a 23% increase in stream functional units and a 40% increase in wetland functional units.

“It tells a great story of what modern mining can do on a brownfield site if we bring this technology to bring uplift to this river,” Lyon said.

“In Idaho, the story of salmon swimming back is a heroic one.”