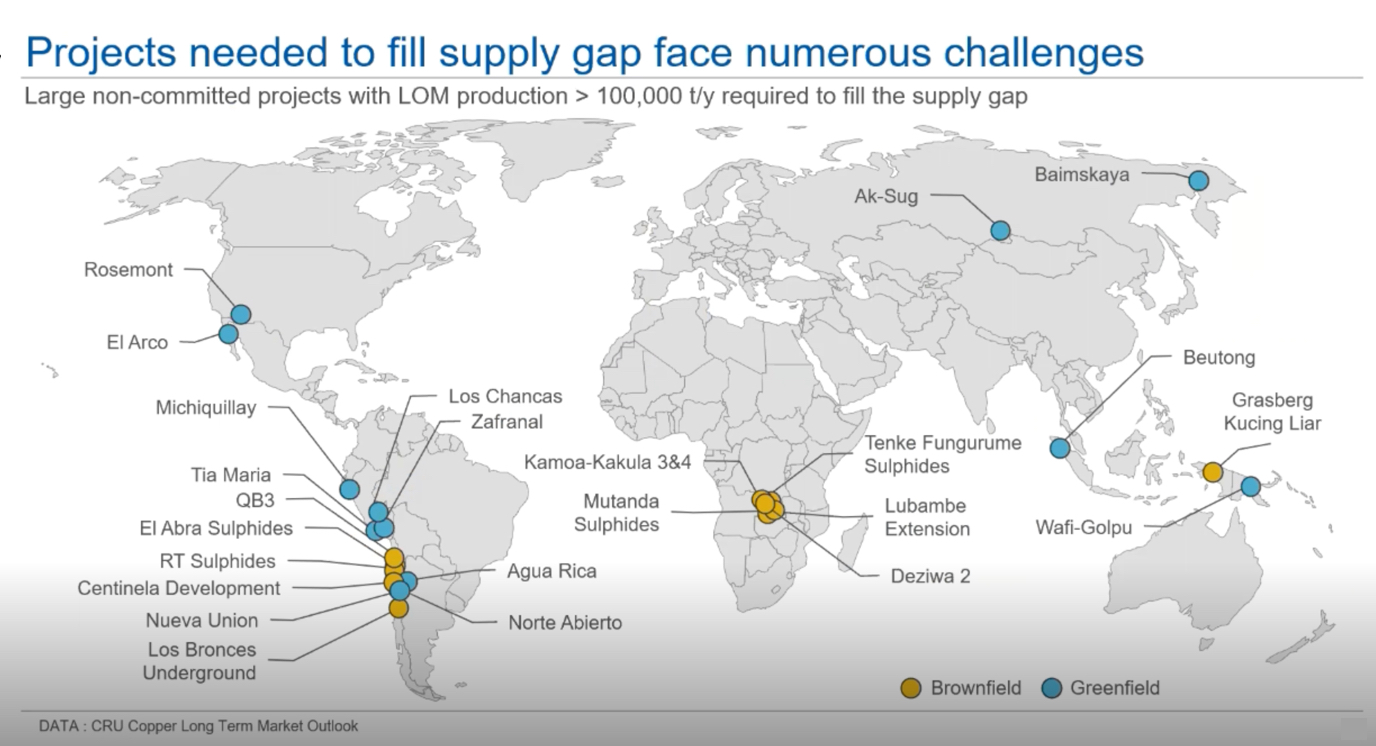

MAPPED: These 25 projects will set the copper price for decades

Erik Heimlich, principal copper analyst at CRU Group, at a recent seminar titled Navigating the green revolution in base metals pointed to a 5.9 million tonne long-term supply gap opening up from the mid-2020s.

The 10-year supply gap compares to annual mine production of little over 20 million tonnes last year and refers to the difference between demand and primary output from existing and projects already committed to.

Heimlich says the industry is not confronting a supply gap that is particularly daunting by historical standards – it’s been above 5 million tonnes for the last seven years, including in 2015 and 2016 when commodity markets were at the bottom of a brutal downcycle and copper was worth half what it is now.

Nevertheless, the industry faces numerous challenges to plug this gap, with developers forced to, according to Heimlich, maneuver an increasingly complex and fraught process to move these projects into production.

Permit delayed is permit denied

Heimlich says mounting ESG concerns and stakeholder demands will change project approval trends in the industry over the coming decades.

Environmental, local community and land ownership issues, with politicians and NGOs happy to fan the flames, present a major obstacle for many of these projects and those that look probable today can quickly move into the possible or speculative bracket.

Hudbay Minerals’ Rosemont copper project, for instance, has been stuck in permitting hell for more than a decade as an already lengthy review and consultation process is complicated by different authorities fighting over which has jurisdiction.

The outcome of an appeal by the Toronto company after a lower court struck down a US Forest Service mine plan approval, is only expected late this year. (For its part Forest told Fish and Wildlife to restart consultation after cameras spotted ocelots in the area – that was seven years ago).

In April, the EPA said the Army Corps of Engineers violated federal policy after it decided the mine does not need permits under the Clean Water Act. And back and forth it goes.

Although extreme, Rosemont’s aggravations are not atypical. An environmental permit that was granted for Wafi-Golpu, Harmony Gold and Newcrest Mining’s joint venture in Papua New Guinea, also went back before the courts last month over objections to plans for deep-sea tailings disposal.

Also in April, a Chilean court ordered a special review of the impact on Indigenous people of Norte Abierto, a greenfield project jointly owned by Barrick and Newmont, both of which have been touting their copper ambitions to investors recently.

Build it and they will come with new taxes

Pedro Castillo’s election may have put the final nail in Southern Copper’s Tia Maria project in Peru (a 70% tax rate will do that) which had been halted twice before over deadly community and environmental protests.

Chile’s new royalty regime is likely to be watered down, but if your starting point is three-quarters of profits at the ruling copper price, you’re going to need a lot of water.

Over and above the tortuous permitting processes, environmental considerations can also wreak havoc on project economics.

Anglo American’s $3 billion Los Bronces underground expansion proposal, for instance, will employ the sub-level stoping method in order to have no surface impact in an area with many glaciers, but doing so means significantly lower ore extraction than with block caving or open-pit operation. Permitting for the 150ktpa project is expected to take three years before construction can start.

Bigging up and blending out

Infrastructure costs are also rising (those desalination plants and power lines don’t come cheap) and with lower and lower ore grades ever bigger operations have to be built.

Kaz Minerals’ proposed Baimskaya mine (at 70 million tonnes of ore a year, no minnow) in the remote Chukotka region is a good example of how these outlays can balloon. And through no fault of the developer.

Kaz saw the project’s cost pop to $8 billion after a Russian government decision that the miner will have to contribute to new infrastructure plans for the region. The soon-to-be-private Kazakh miner duly delayed the project by at least a year.

Building bigger creates its own problems with greater proportions of deleterious material like arsenic, antimony and bismuth ending up in concentrates. And blending as a solution only works for so long because, well, who are you going to blend with if everyone has the same problem?

Miners clearly have the upper hand in the TC/RCs tug of war at the moment although charges have been creeping up from historical lows and are back above $30 a tonne this week.

Not that long ago, smelters – dealing with their own environmental restrictions – were confident enough to refuse material with high impurities and squeeze miners on payables.

Dollars and incentives

According to Heimlich, the current copper price provides ample incentive to build these mines, and projects in CRU’s probable category would cover the bulk of the expected shortfall.

Moreover, capital intensity for new copper projects has been stable in recent years despite all the project management and budgetary tales of woe.

From 2009 to 2015, capital required per tonne of production capacity surged from just over $10,000 a tonne to the vicinity of $20,000, where it remains today.

Many of the projects shown on the graph (uncommitted with life-of-mine production of more than 100,000 tonnes per annum) are owned by the same companies because much like iron ore, copper is increasingly becoming a game for big players only.

Heimlich says should capex costs escalate at the rate seen during the first half of the last decade it will create problems for boards who’d have to carefully pick their fights.

And fights they will be.