What the 10-year Treasury rate’s dip below 1.5% may be saying about inflation

A key market signal on inflation has taken a dip ahead of the second half of 2021.

When the benchmark 10-year Treasury rate quickly climbed to 1.7% in March, Wall Street went on high alert, worrying about the Federal Reserve’s potential to go overboard with its support for the economy during the pandemic, while risking an inflation hangover of the likes not seen since the 1970s.

Now, three months later, the 10-year yield TMUBMUSD10Y,

What does that mean for inflation expectations? “The 10-year Treasury is signaling that we are not going to get sustained inflation above 2%,” Kathy Jones, chief fixed income strategist at Schwab Center for Financial Research, told MarketWatch.

“I think the 10-year isn’t so much reflecting the impact of QE, as it’s replaying a scenario that happened after the 2008 crisis,” Jones said, speaking in shorthand for the Fed’s restart of “quantitative easing” at the onset of the pandemic, with a massive $120 billion-a-month program of buying Treasurys and mortgage-backed securities MBB,

“The worry is that fiscal stimulus may be fading too soon and the economy is not really getting back to full growth and labor-market participation,” Jones said. “That’s where we are.”

Higher costs are here

That isn’t to say the recent spike in the cost of living, to its highest level in more than a decade, doesn’t matter.

“I don’t think the market is saying there isn’t a spike in inflation,” said Eric Souza, senior portfolio manager at SVB Asset Management. “There is higher inflation right now. There is no doubt about it. But will these increases persist?”

“I feel the answer is ‘no’ when you think historically where prices have been,” he told MarketWatch, pointing to globalization and advancements in technology that in the past have kept major price increases at bay.

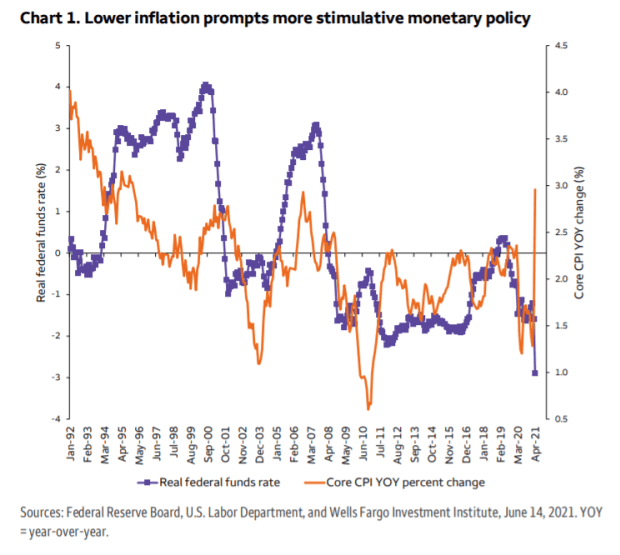

Despite monetary stimulus, the Fed has struggled to keep inflation at its 2% target over the past 25 years.

Fed’s past use of stimulus to try to boost inflation.

Wells Fargo Investment Institute

The above chart overlays an inflation-adjusted federal-funds rate with the trajectory of year-over-year changes in the Core Consumer Price Index, a measure of inflation.

Besides inflation, Souza outlined other factors also playing a role in the Treasury market in recent months, particularly with pension funds and asset allocators growing more nervous about record stock prices SPX,

“The 10-year Treasury is the S&P 500 of the bond market,” Souza said. “And now you’re having another set of buyers coming back in,” he said, referencing large foreign buyers, including Japan, who have recently increased their Treasury debt holdings.

“Given low global yields, and from a liquidity perspective, it makes sense at those elevated yields,” Souza said.

Looking ahead

While Fed officials have yet to decide when the central bank might start scaling back its monthly bond-buying program, they have begun discussing it.

Over the past 15 months, Fed asset purchases have helped keep credit flush during the pandemic and borrowing costs low for households and corporations. But as the economy and labor market heals, the central bank has signaled that interest rates could rise from the current 0%-to-0.25% range more quickly than initially anticipated.

On the other hand, the economic jolt from trillions worth of fiscal stimulus from Washington, including extra unemployment benefits and lump-sum payments to U.S. households, already has begun to fade from peak levels.

George Cipolloni, a portfolio manager at Penn Mutual Asset Management, said that while global forces impact the U.S. Treasury market, the 10-year’s rate slump also likely reflects domestic economic headwinds.

“We have been the least dirty shirt in the laundry, and we still are,” Cipolloni said of the Treasury market’s standing in a world awash in negative- and low-yielding bonds.

“But I do think, in the U.S., we are going to run through a cyclical wave of above-normal inflation rates,” he said, while also pointing to price pressures that have begun to wane, along with supply-chain disruptions that reared up in the early reopening phases of the pandemic.

“You saw lumber LB00,

More concerning, Cipolloni pointed to the massive increase in the U.S. debt levels during the pandemic, which could easily weigh on U.S. GDP growth down the road, even as the second quarter is expected to see an 8.2% annualized rate.

And despite the piles of pandemic stimulus adding liquidity to markets, banks since April have been parking increasingly vast sums — at last check a record $841 billion — overnight in the Fed’s overnight reverse repo facility, earning 5 basis points, instead of using the cash and deposits for lending.

“Unfortunately, I don’t know if there is a great way out of the situation we are in,” Cipolloni said.