Almost all people hospitalized for Covid-19 are not vaccinated — 99.9% as of May to be exact, according to a recent Associated Press report.

Yet 13% of U.S. adults said they will “definitely not” get a COVID-19 vaccine as recently as late May, according to Kaiser Family Foundation COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor. Another 12% wanted to “wait until it has been available for a while to see how it is working for other people.”

Vaccinating the majority of the population is the best way to help avoid further surges from constantly evolving variants, like the current delta variant, which is quickly spreading in the U.S. and other countries.

Still, Moderna co-founder Noubar Afeyan understands the hesitation to get a new vaccine.

“The vaccines came out in such a [short] timeframe that people assumed automatically, it can’t possibly be safe,” Afeyan said during a talk at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in May.

“In fact, many, many people were on television espousing the view that — experts for that matter — that if it’s done in less than five years, it’s got to be unsafe, all of which is untrue.

“Nevertheless, people get confused.”

What people might not understand is that extensive research was being done on mRNA technology and other mRNA vaccines for years. That decade plus of experience and the innovation of mRNA technology itself is what allowed Moderna to produce its Covid mRNA vaccine so quickly as the pandemic struck. And it could also change the future of medicine.

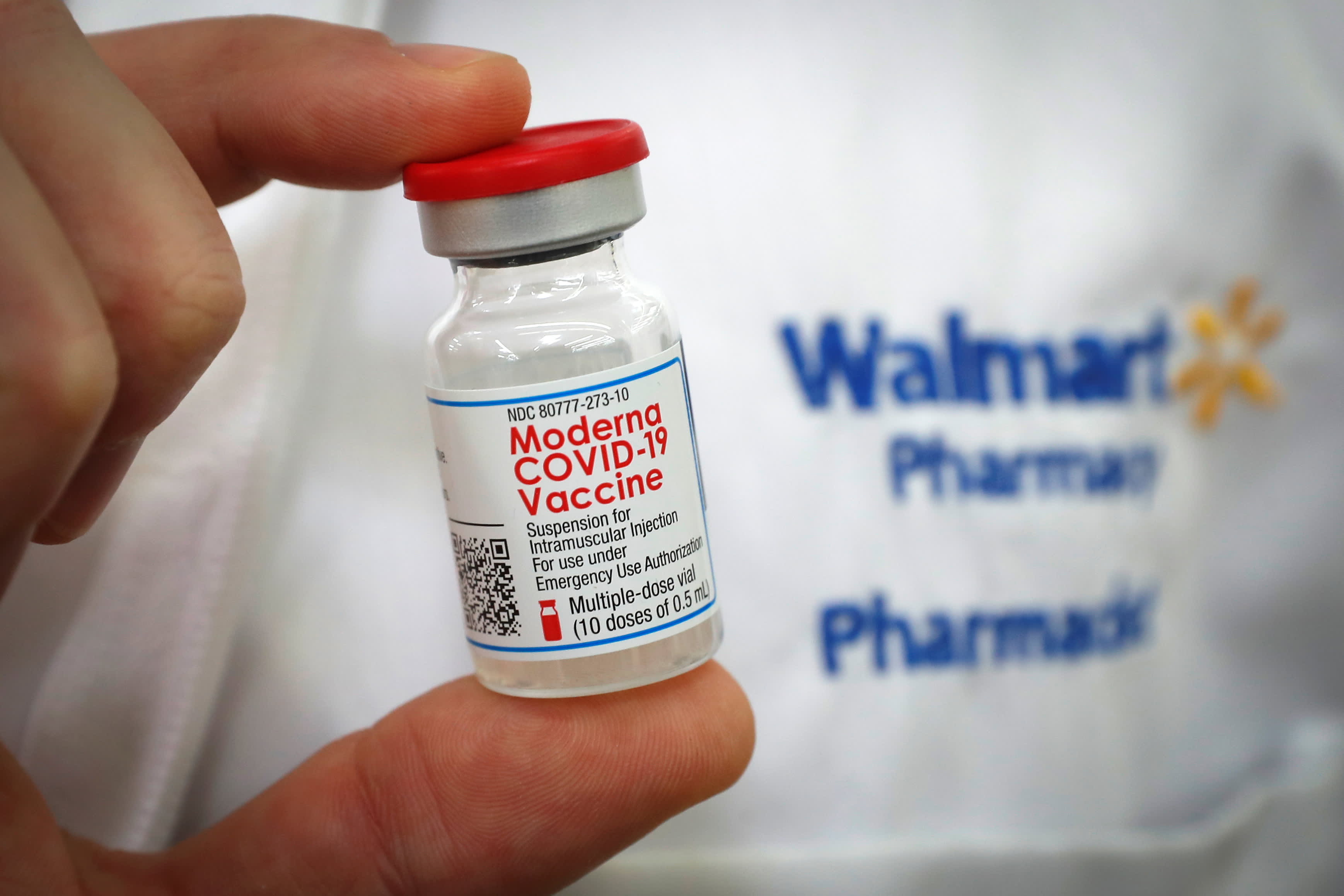

Here’s what you need to know about how the Moderna Covid-19 mRNA vaccine was developed.

The timeline: A vaccine in under a year

It is true that Moderna’s mRNA vaccine was ready remarkably fast, as was Pfizer’s.

Chinese scientists put the genetic sequence of the novel coronavirus online on Jan. 11. Over the next two days, the NIH and Moderna used it to plot out a vaccine.

Afeyan remembers getting a key call about the development of the Covid-19 vaccine. “January 21st, my daughter’s birthday…. I got a call from Davos [during The World Economic Forum] from the CEO of Moderna,” he says. Bancel had been approached by a number of public health groups at the conference “urging” him to work on a vaccine.

“We literally Decided overnight…to try and do this,” Afeyan said at MIT.

Moderna delivered the first doses of its Covid-19 vaccine to the NIH for testing on Feb. 24, 2020, and “the first Moderna shot went into a volunteer’s arm in Seattle on March 16, 2020,” according to Afeyan.

After testing the Moderna vaccine on 30,000 volunteers, on Dec. 18, 2020, the FDA authorized it for emergency public use, and three days after that, the first Moderna vaccines were administered to front-line health workers, according to Afeyan.

Over a decade of research to innovate mRNA as a ‘bioplatform’

One of the reasons Moderna’s mRNA Covid vaccine development moved so quickly is because scientists had been working with mRNA for years.

“Messenger RNA technologies have been in development from a basic science perspective for over 15 years,” Kizzmekia Corbet, the scientific lead for the Coronavirus Vaccines & Immunopathogenesis Team at NIH, who helped make the vaccine possible, told the NIH Record.

And Moderna has been working with mRNA technology “since its inception in 2010 for myriad therapeutic areas,” including cancer therapies, Afeyan tells CNBC Make It (by way of a publicist), and with clinical development of mRNA-based antiviral vaccines since 2015.

What Moderna did over many of those years was develop mRNA as what scientists call a bioplatform, which allows for speedier vaccine development. Bioplatforms are systems that can easily be scaled and tailored for many different diseases.

Traditionally, developing any vaccine essentially has been a bespoke effort.

“The benefits of a bioplatform is the ability to quickly redeploy the platform once established and refined –in the case of Moderna’s mRNA platform, to create and test new vaccines based on new viral sequences,” Afeyan tells CNBC Make It (by way of a publicist).

All of this makes mRNA vaccines virtually programable. Corbet and Bancel describe the process as “plug and play.”

“MRNA is always made of four same letters, Bancel said on the December Andreessen Horowitz podcast, “Bio Eats the World.” (MRNA is genetic material, similar to DNA, so its “code” is expressed with letters.) It’s “the four letters of life, like zeros and one in software,” said Bancel. “This is like software or LEGO.”

“The only difference between” mRNA vaccines is “the order of the letter; the zeroes and ones of life,” Bancel said. “The manufacturing process is the same, the equipment is the same, with the same operators. It’s the same thing. And so this is why we could go so fast.”

Faster vaccine development in the future

Bioplatforms will effect change way beyond the Covid pandemic.

Judy Savitskaya and Jorge Conde, biotech investors for top Silicon Valley investment house Andreessen Horowitz liken how bioplatforms could change the biotechnology industry to what the advent assembly lines did for the auto industry: It “went from single ‘job shops’ in the early days of automobiles — where raw materials like steel and rubber crafted from start to finish by hand into a trickle of early cars — to assembly line production, with standard components that could be iterated for new models,” they wrote in a January blog post.

(Andreessen Horowitz is not an investor in invested in Moderna, Pfizer or BioNTech, according to a firm spokesperson.)

The Covid-19 vaccine is one example of how mRNA can be used.

Moderna has 24 mRNA vaccines and therapeutics under investigation, and 14 have begun clinical studies, according to the company’s quarterly investment documents published in May. Moderna’s pipeline of mRNA treatments include a zika vaccine, HIV vaccine and a cancer vaccine, to name a few.

The same dynamic enabled Pfizer and BioNTech, who collaborated to create the other mRNA Covid vaccine currently in use in the U.S., “to rapidly redirect its mRNA technology platform from cancer to COVID in a matter of weeks; the company estimates it can manufacture updated versions against emerging mutant strains in as little as six weeks,” Savitskaya and Conde write.

Pfizer and BioNTech are also working on an mRNA vaccine to prevent the flu.

“[T]hese programs are just the first in a long list coming that will benefit from the same underlying [bio]platforms,” wrote Savitskaya and Conde. “The rise of productive platforms will impact much more than just vaccines. It will transform all areas of biotech, from small molecule discovery, protein engineering, genome editing, gene delivery, cell therapy, and more.”

Even with all this hard work and innovation, even Afeyan says Moderna got lucky to be able to move as quickly as it did.

“I’m quite actually amazed,” Afeyan said at MIT. “Murphy’s Law was on vacation, was on sabbatical for a whole year, and so many things that could have gone wrong, simply did not.”

See also:

This biotech start-up is working overtime to develop a mutation-resistant Covid-19 vaccine

Merck CEO on success: I was one of a ‘few inner city black kids’ who rode bus 90 minutes to school