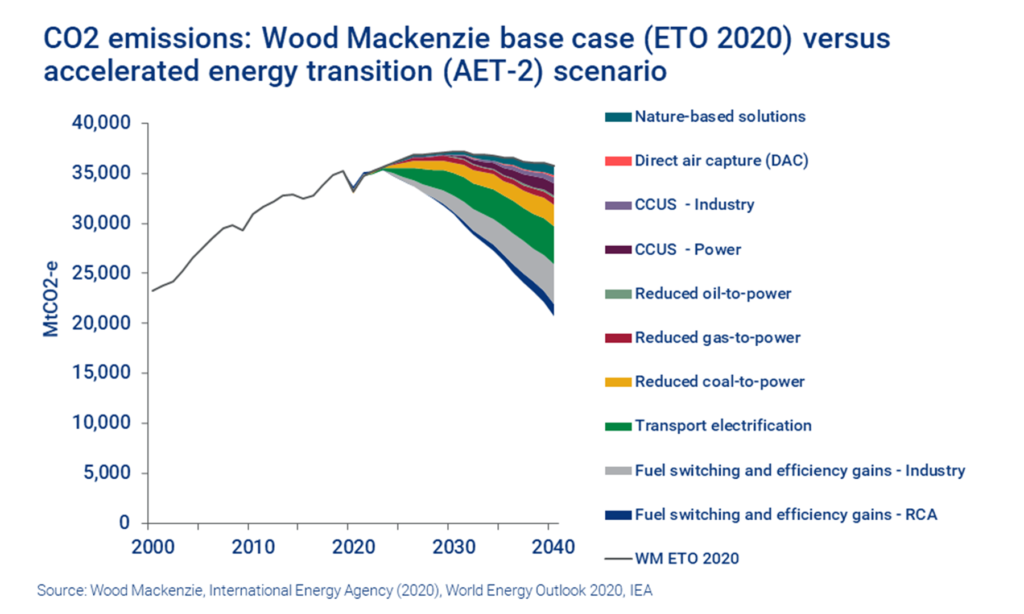

Based on WoodMac’s estimations, limiting the average global warming to two degrees above pre-industrial levels would require the elimination from the global economy of around 17,000 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions by 2040, compared with 2020 levels. Meanwhile, by 2030 the reduction required is ‘only’ 7,500 Mt CO2-e – still a huge target, especially given that on current projections emissions are set to continue to rise until at least 2025.

The problem is that certain sectors, such as the steel and aluminum industries, loom large when it comes to fuel switching and, together, they represent more than 10% of global emissions.

“Steel will require a truly monumental shift into hydrogen-based production. This is likely to start with direct reduced iron and the adoption of innovations such as Hydrogen Breakthrough Mining Technology (HYBRIT),” Kettle wrote in his analysis. “Greater use of low-carbon energy to fuel scrap processing will also help. The widespread availability of green hydrogen will therefore determine the rate of decarbonization of steel production. However, the challenge is that the cost of the technological solution to decarbonization, or carbon abatement cost, is more than $200 per tonne of CO2-e.”

When it comes to aluminum, Kettle said that while the use of inert anode technology and low-carbon processing of bauxite will play a part, the most significant carbon reduction will come from the use of low-carbon power.

In his view, greater recovery and processing of scrap will also play a large role, but only if low-carbon power is available. The costs of carbon abatement for aluminum therefore chiefly relate to long-duration renewables, which are in the range of $50-150 per tonne of CO2-e.

“In short, the rate-determining step in the decarbonization of steel and aluminum will be the widespread availability of green hydrogen for the former and low carbon power for the latter,” his review reads. “Without an alignment between carbon taxes, emissions caps and the cost of abatement, the economics of green steel and aluminum won’t stack up. It will not be possible to state the decarbonization aspirations of industry and consumers at the same time.”

Electric vehicles

Taking into consideration the recent EV boom, Kettle explained that in order to follow the AET-2 pathway, by 2025 EV sales would have to reach around 50 million units, and by 2030 around 85 million units.

However, he believes the biggest question is whether the mining industry will be able to deliver the tonnage necessary to ramp up battery production facilities fast enough.

“My considered opinion is unequivocal: the numbers simply don’t add up in terms of the scale and speed of the buildout of mine supply required and processing capacity needed to deliver on a two-degree pathway,” Kettle wrote.

The analyst pointed out that under Wood Mackenzie’s base case, battery EV, plug-in hybrid and hybrid build and sales reach around 20 million units by 2025 and around 50 million units by 2030.

For the market researcher, such numbers can be managed by the raw materials supply chain, albeit with some thrifting and innovation.

The role of policy

Kettle also pointed out that another issue hindering a proper global move towards a cleaner future is the low price attached to carbon emissions and the low coverage of emissions trading schemes.

“This reality becomes stark when we consider that our AET-2 scenario assumes a global carbon tax of $110 per tonne by 2030. At present, very few countries have any carbon taxes at all, and even when they do the coverage is small in comparison to total emissions and the level of taxation is pitifully low,” the analysis states.

Wood Mackenzie expects a massive lag between the delivery targets of a low carbon world and the reality until carbon taxes and emissions trading prices become aligned and grow in significance.