In a presentation at the Goldschmidt Conference organized by the Washington-based Geochemical Society, the researchers explained that they used high-precision isotopic analysis to identify the ore sources of minute lead traces found in hacksilber.

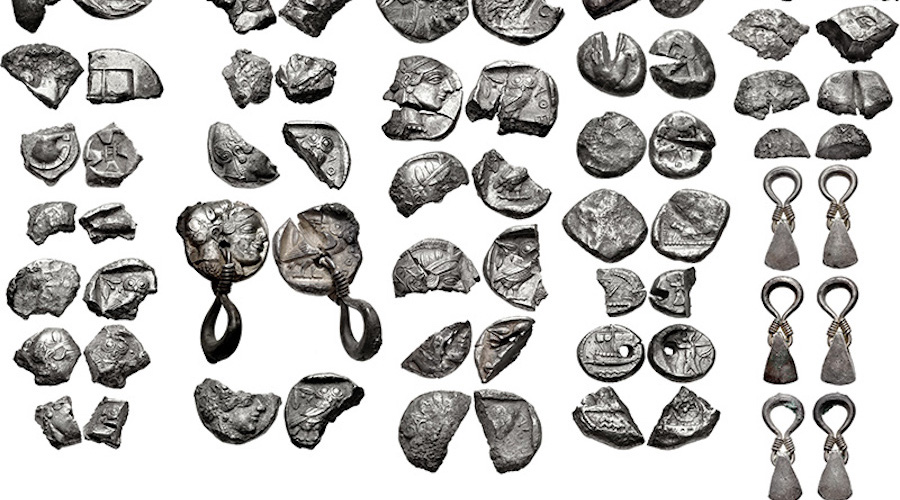

Hacksilber is an irregularly cut silver bullion including broken pieces of silver ingots and jewellery that served as means of payment in the southern Levant from the beginning of the second millennium until the fourth century BCE. Used in local and international transactions, its value was determined by weighing it on scales against standardized weights.

Previous reports from archaeological excavations showed that hacksilber was usually stored inside ceramic containers and noted that it had to be imported as there was no silver to be mined in the Levant.

Based on this information, the team led by Liesel Gentelli from the École Normale Supérieure de Lyon, France, analyzed hacksilber from 13 different sites dating from 1300 BCE to 586 BCE in the southern Levant, modern-day Israel and the Palestinian Authority.

Most of the hacksilber dating from 1300 BCE to 586 BCE came from the southern Aegean and Balkans. Some of it was also found to come from as far away as Sardinia and Spain

The samples included finds from “En Gedi, Ekron, and Megiddo” (also known as Armageddon). They matched their findings with ore samples, and have shown that most of the hacksilber came from the southern Aegean and Balkans (Macedonia, Thrace and Illyria). Some of it was also found to come from as far away as Sardinia and Spain.

“Previous researchers believed that silver trade had come to an end following the societal collapse at the end of the Late Bronze Age, but our research shows that exchanges between especially the southern Levant and the Aegean world never came to a stop,” Gentelli said. “People around the eastern Mediterranean remained connected. It’s likely that the silver flowed to the Levant as a result of trade or plunder.”

According to the scientist, the periods of silver scarcity occurred around the time of the Bronze to Iron Age transition, around 1300-1100 BCE, and some hoards from this period show the silver displaying unusually high copper content, which would have been added to make up for the lack of the grey metal.

“We can’t match our findings on the silver trade to specific historical events, but our analysis shows the importance of hacksilber trade from before the Trojan War, which some scholars date to the early 12th century BCE, through the founding of Rome in 753 BCE, and up to the end of the Iron Age in 586 BCE, marked by Nebuchadnezzar’s destruction of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem,” Gentelli pointed out.

The researcher also said that after these events, there was a gradual introduction of coinage, first as finds of several archaic coins and later a transition to a monetary economy in the southern Levant circa 450 BCE which made the trade of hacksilber less relevant.

“However, this work reveals the ongoing and crucial economic role that Hacksilber played in the Bronze and Iron Ages economies,” he said.