Here’s what’s next for the $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill

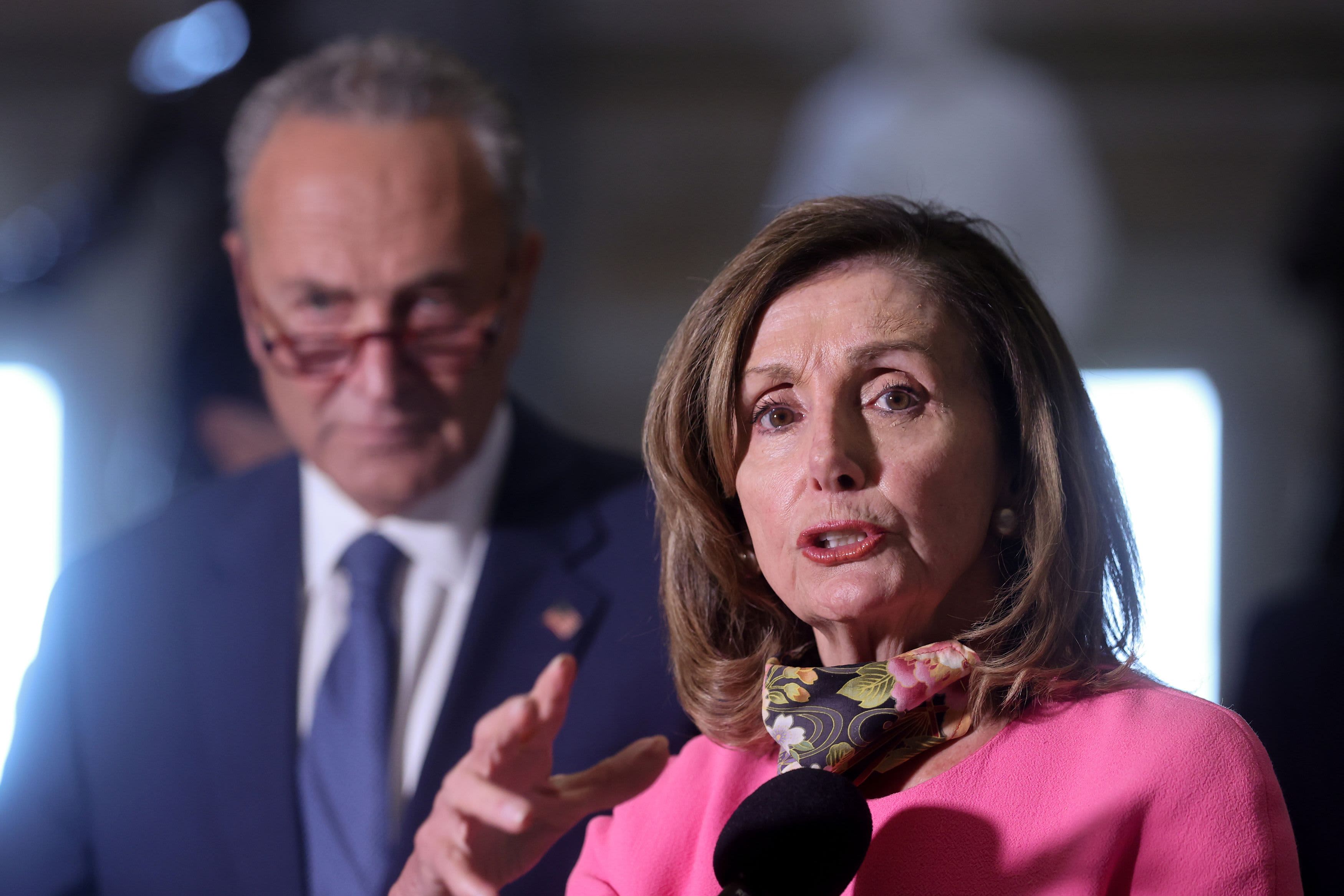

U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) speak to reporters after their coronavirus relief negotiations with Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, U.S. August 7, 2020.

Jonathan Ernst | Reuters

The Senate on Tuesday passed a $1 trillion infrastructure package, sending the provision to improve the nation’s roads, bridges and broadband to the House for approval.

But progressive Democrats in the House, eager to make good on campaign promises ahead of the 2022 midterms, could pose a new set of hurdles to the bipartisan infrastructure plan.

Progressives aren’t expected to make dramatic changes to the infrastructure bill, but they insist that the Senate first pass a separate $3.5 trillion bill focused on poverty, climate change and health care.

The House is expected back from its recess Sept. 20.

The infrastructure proposal is the product of months of haggling between Republicans and Democrats and includes more than $500 billion above projected federal spending on upgrading the country’s transportation systems.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., praised the bipartisan work in remarks moments before the bill’s passage.

“It’s been a long and winding road, but we have persisted and now we have arrived,” Schumer said from the floor. “The American people will now see the most robust injection of funds into infrastructure in decades.”

The bipartisan bill strengthens “every major category of our country’s physical infrastructure,” he added. “Today, the Senate takes a decades-overdue step to revitalize America’s infrastructure, and give our workers, our businesses, our economy the tools to succeed in the 21st century.”

The 2,700-page infrastructure bill now makes its way to the House, where some progressives have said that they won’t support it until the Senate passes the separate $3.5 trillion bill that tackles poverty, climate change and health care.

Schumer brought up the budget resolution immediately after the infrastructure bill’s passage and before the Senate headed to recess this week. The Senate is set to return for a few days Sept. 13 and then for a longer period starting Sept. 20.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., has backed that position and said she won’t bring up the infrastructure bill in her chamber until the Senate passes the sprawling budgetary proposal.

Senate Democrats released that budget outline on Monday, which includes universal prekindergarten, two free years of community college, boosted Medicare and other provisions. Schumer hopes to approve the outline for that bill and muscle the entire package through the chamber to the House via a special process known as reconciliation.

While reconciliation would allow Democrats to pass the sprawling budget resolution with a simple majority vote, keeping the entire 50-person caucus behind a bill that includes tax increases could prove tricky.

Republicans in both chambers remained united against the second package as an expensive packaged laden with partisan priorities. But some moderate Democrats, including Sens. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., and Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., worry about the plan’s price tag or overheating the U.S. economy.

But if Pelosi’s plan to wait for this second bill works, it would make good on Democrats’ campaign promises to enact generational infrastructure, climate change and pro-worker legislation.

That could prove key to the House speaker’s odds of maintaining her majority in the House, which political analysts say is at risk of swinging into the hands of the GOP in the 2022 midterm elections. But with a bill as large as $3.5 trillion, House Democrats may need time to sort out the details of the plan.

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., conducts news conference in the Capitol Visitor Center with House Democrats on achievements including the For The People Act and the agenda for the remainder of the year, on Friday, July 30, 2021.

Tom Williams | CQ-Roll Call, Inc. | Getty Images

If the House’s version includes material changes to the Senate’s, lawmakers from both chambers would then work together in a conference committee to reconcile their differences and produce a final bill.

That bill would then return to each chamber for a vote before heading to President Joe Biden’s desk.

Alternatively, the Senate could simply adopt the House’s rewrite and avoid the complicated step of trying to sort out differences between the two chambers in conference committee.

As for when the infrastructure money starts flowing, it could be as soon as a couple months for projects that already have permits and contractors. The other money could take about a year to be disbursed, depending on approvals for projects from state and local governments.