Stealthy battery company backed by Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos has a lot to prove

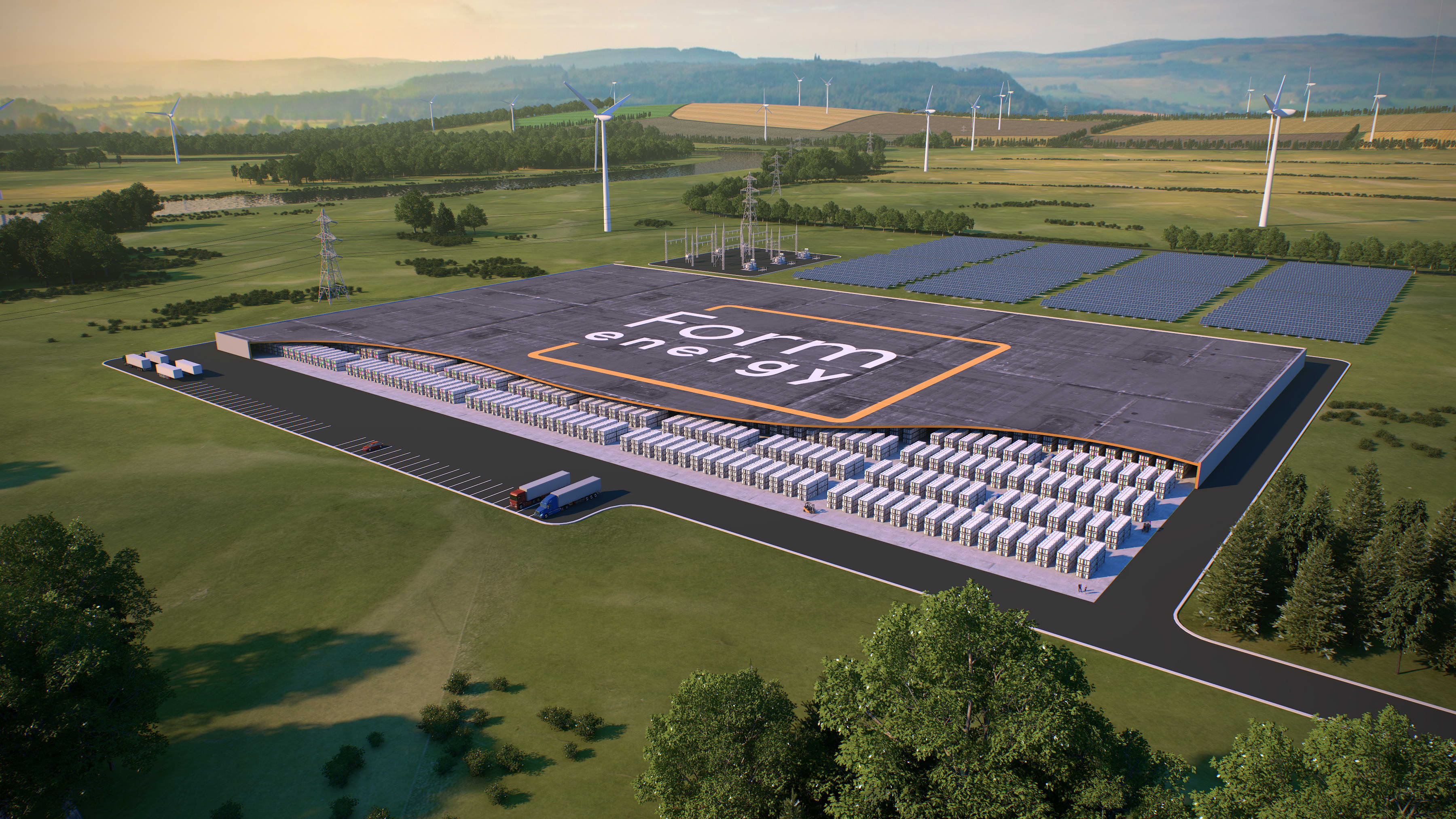

An artist rendering of Form Energy’s battery system.

Rendering courtesy Form Energy

A secretive start-up called Form Energy says it’s developing and scaling the production of a new type of rechargeable battery that can store electricity for 100 hours.

Form hasn’t publicly demonstrated its technology or shared proof that it works. Nonetheless, the company has lined up more than $360 million in funding, including a new $240 million round that closed Tuesday, and partners and outside experts are optimistic about its potential.

Form Energy’s core technology is based on three cheap and readily available materials: Iron, air, and water. The battery works with a process the company calls “reversible rusting,” in which the battery charges and discharges by converting iron back and forth into rust. By using these inexpensive materials, the company aims to have its batteries cost less than $20 per kilowatt-hour, which experts say is up to one-tenth the cost of the more common lithium-ion batteries in use today.

In order for carbon emissions to hit net-zero by mid-century, meaning that the globe is absorbing as much greenhouse gases as are still being emitted, solar and wind capacity will need to quadruple and investments in renewable energy will need to triple by 2030, according to comments from United Nations Secretary General António Guterres.

For that to happen, there also must be a ramp up of long duration battery storage. There has to be a way to provide electricity when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing. That’s the market Form Energy is attempting to serve.

One notable funder is Breakthrough Energy Ventures, which includes tech celebrities Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Reid Hoffman and Richard Branson as investors. In one of his blog posts, Bill Gates touted the importance of Form Energy’s work, writing that it was “creating a new class of batteries that would provide long-duration storage at a lower cost than lithium ion batteries.”

Its first utility partner, Minnesota-based Great River Energy, describes their work together as a pilot project that could be an “important contribution to grid reliability and energy affordability should they achieve commercial success,” a spokesperson says.

No public data, lots of faith

Until recently, the company had been operating under the radar. In October 2019, CEO Mateo Jaramillo, a former Tesla vice president, noted his own reticence to speak with the media.

“As you’ve maybe seen, there isn’t a lot of press about us. And we’ve tried to tamp down anything other than what’s necessary,” he told CNBC at the time, speaking at the Tough Tech Summit in Boston, in the backyard of the company’s headquarters in Somerville, Mass. “There’s just a fraught history with battery startups over the last 15 years. Which is why that hesitancy in general. The industry is a little weary, I would say.”

Despite the company’s early tendency to skirt the spotlight, it’s had no trouble raising funds. On Tuesday, Form Energy announced it had closed a $240 million Series D financing round, led by the decarbonization XCarb innovation fund of the global steel manufacturer ArcelorMittal. Form Energy and ArcelorMittal are working together to develop iron materials for Form’s first commercial battery technology which “ArcelorMittal would non-exclusively supply for Form’s battery systems,” according to a statement. Breakthrough Energy Ventures also participated in the round.

However, Form has released no public data to verify the performance of its long-duration battery technology. (The company prefers the term “multi-day storage” to differentiate it from other companies working on shorter-long-duration batteries.)

The Form Energy battery.

Photo courtesy Form Energy

“We have been doing extensive testing internally. But you asked about public data. There is no public data, we don’t publish public data. We’re a private company, so we don’t need to,” Jaramillo told CNBC in a phone conversation in August.

“We are extremely transparent with our partners … about the testing that we have, the cells that we’re building and testing … but all of the structure of our experiments and exactly what goes in there that’s quite proprietary,” Jaramillo said.

CNBC spoke with several of these funders and partners to learn what they saw in the company’s technology.

Great River Energy is working with Form Energy to implement a one-megawatt battery storage pilot project in Cambridge, Minn. Form Energy’s battery technology depends on having access to iron, and a swath of northern Minnesota is called the Iron Range for its extensive deposits.

The management and technical teams of Form Energy and Great River have been collaborating for more than three years, says Jon Brekke, vice president and chief power supply officer for the utility.

“During this time, Form has shared with us plans, actions, and results of their technology development work that directly supports our pilot project,” Brekke told CNBC. “A shared vision of low cost, long duration storage led us to this pilot project. We see these efforts as an important contribution to grid reliability and energy affordability should they achieve commercial success.”

While Great River Energy reports to have seen evidence of Form Energy’s battery tech working, the California Energy Commission, from which Form Energy won a $2 million dollar grant, has not.

In June 2020, the California Energy Commission, the state’s primary energy policy and planning agency, granted Form Energy the money to be used for pursuing the development of energy storage technologies that do not require lithium. “Grants are awarded on a competitive basis, meaning they are scored based on their technical merit,” Michael Ward, spokesperson for the California Energy Commission told CNBC.

That said, the California Energy Commission “has not seen specific performance data on the iron-air technology yet,” according to CEC researcher Mike Gravely. It expects to “receive that data when the system is built and tested” at a test site at the University of California at Irvine.

Form Energy’s air electrode, a component of its battery technology.

Photo courtesy Form Energy

A co-chair of the investment committee at Breakthrough Energy Ventures, Carmichael Roberts, said the firm would not comment on the performance of Form Energy’s technology. However, he told CNBC the caliber of the personnel gave the Breakthrough team the confidence to invest.

“When we started Breakthrough Energy Ventures, we knew that long duration energy storage was going to be an important part of the portfolio. When we learned that Yet-Ming and Mateo were each creating a new battery company, we saw it as the perfect opportunity to bring together two of the world’s leading experts, and Form was launched,” Roberts told CNBC. Yet-Ming Chiang is a co-founder and the chief scientist at Form Energy, and a professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology since 1985.

“We knew that the core technology had great potential, but more importantly we had faith in the team that could deliver it,” Roberts said.

The rechargeable iron-air battery Form Energy is not the only technology the company has pursued.

In 2018, Form Energy received $3.8 million from the federal government’s Department of Energy as a part of the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Energy (abbreviated as ARPA-E). But that was for a different battery based on “aqueous sulfur battery chemistry,” Form told CNBC.

“We chose to focus on an iron-air battery as our first commercial offering both because of its promising performance in the lab and because the iron-air chemistry positions us to tap into the global iron supply chain that already exists to support steel manufacturing,” the company said.

How iron-air battery tech works

The essential ingredients in Form’s battery are iron, air and water, all readily available and low cost.

To charge, an electric current converts rust back to iron and the battery breathes out oxygen. To discharge, the battery takes in oxygen from the air and converts the iron to rust.

Each battery is filled with a non-flammable electrolyte liquid, similar to the electrolyte used in AA batteries, and is about the size of a washing machine, Form Energy says. Thousands of the washing machine-size battery modules are clumped together in power blocks and depending on what is needed, tens to hundreds of power blocks can be connected to the electricity grid.

A diagram of the Form Energy iron-air battery technology.

Form Energy

The idea behind the technology is not new. “You can get something to rust, obviously. Rust happens all the time,” Jaramillo told CNBC. “To better control that process and to control it at its least cost, most performing points is an altogether separate matter.”

Experts agree that the technology has promise.

“There is obvious economic potential if iron can substitute for expensive precious metals such as cobalt, nickel and lithium,” says Stefan Reichelstein, an accounting professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Business whose recent work includes studying the cost competitiveness of low-carbon energy solutions.

“But the information disclosed thus far leaves open the key question: What is the unit cost of storing (and discharging) electricity in relatively few — rather than daily — cycles each year?” he added.

The cost question

Form Energy aims to have its battery cost less than $20 per kilowatt-hour, the company tells CNBC. If the company can deliver on that cost goal, it would be a meaningful advance, experts say.

“From an economics point of view, Form’s announced cost target of $20 per kilowatt-hour is in line with what we found in our study published in Nature Energy to be the cost level required for long-duration energy storage to play a significant role in decarbonization of energy systems,” Nestor Sepulveda, who holds a Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in developing methodologies that combine operations research and analytics to guide the energy transition and cleantech development, told CNBC.

By comparison, lithium-ion batteries cost between $100 and $200 per kilowatt-hour, explained Mark Z. Jacobson, a professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Stanford.

Form Energy’s iron anode, a component of its battery technology.

Photo courtesy Form Energy

“If the cost is actually $20 per kilowatt-hour, that would be a breakthrough and allow the rapid large-scale transformation of all electricity world wide to clean, renewable (wind-water-solar) electricity,” Jacobson said.

Battery tech at the $20 per kilowatt-hour price point “would eliminate the need for natural gas or any other type of combustion fuel for backup power,” Jacobson told CNBC. “It would break any chance of nuclear power from playing a role in an energy future. It would end coal, fuel oil, and natural gas as fuels for electricity generation.”

Sepulveda, who is currently working as a consultant, is a bit more conservative about what $20 per kilowatt-hour means.

He said the threshold is meaningful “with very high penetration of renewables (not our current levels).” So in order for $20 per kilowatt-hour to be meaningful for the quest for carbon reduction, there will have to be more renewable energy production on the ground. “The question then becomes, is there a market in the near future for these technologies? I think that the answer is that there is going to be a niche market for long-duration-energy-storage in the short-medium term, but a big one in the long-term.”

Even while “$20 per kilowatt-hour is very cheap,” Sepulveda and his co-authors determined it the price of long-duration battery storage would need to be less than $10 per kilowatt-hour to “meaningfully displace” other forms of firm energy generation, which refers to energy technologies that can be counted on to meet demand when it is needed in all seasons and over weeks or longer.

The demand for multi-day-battery technology depends on the development of other technologies, too.

“While it seems plausible that iron-air batteries are less expensive than lithium-ion batteries, the more interesting comparison will be with other seasonal storage technologies, for instance, hydrogen conversion,” Reichelstein said to CNBC.