What the growth vs. value stock debate reveals about the bull market’s future

Does the resurgence of value stocks over growth stocks mean the bull market’s days are numbered?

I’m referring to the epic battle between two major stock market styles: growth stocks (those of companies that are growing the fastest and are trading for higher valuations) and value stocks (out of favor companies that are trading for lower valuations).

While value stocks on average over the past century have significantly beaten growth, they have suffered significant periods during which growth has come out on top. The past decade has been one such period.

The tide began to turn in the fall of 2020 in favor of value, causing widespread celebration among value managers that maybe — just maybe — their long period of suffering was ending. Most other managers looked on with bemused attachment, considering the growth-versus-value debate to be little more than an intramural rivalry.

Some observers think that attitude is shortsighted. They believe that growth stocks’ fortunes relative to value stocks may tell us whether or not we’re in a healthy bull market.

On the surface their argument makes sense. Growth stocks presumably will be growing the fastest when the economy is firing on all cylinders. And economic growth is certainly conducive to a bull market on Wall Street. So it stands to reason that a shift in leadership to value from growth might signify an imminent market downturn.

This theoretical argument accords with the stock market’s experience leading up to, and following, the bursting of the internet bubble in 2000. The bull market years of the 1990s were one of the longest periods over the past century in which growth stocks beat value. After that bubble burst, value stocks began one of the longest periods over the past century in which they beat growth.

There are exceptions in the historical record. During the Great Financial Crisis, for example, growth stocks on balance outperformed value. Yet the economy shrunk significantly and the stock market plummeted.

What the data tell us

To get a better handle on this confusing relationship between the market’s health and growth- and value stocks’ relative returns, I analyzed the stock market’s tendencies back to mid-1926, courtesy of data from Dartmouth professor Ken French and Yale University professor Robert Shiller. For each month I obtained data on value’s performance relative to growth, as well as the S&P 500’s SPX,

I searched for correlations between the two and came up empty. There were some periods in which value’s relative strength was associated with lower stock market returns, and others in which it was correlated with higher returns. There was no consistent pattern.

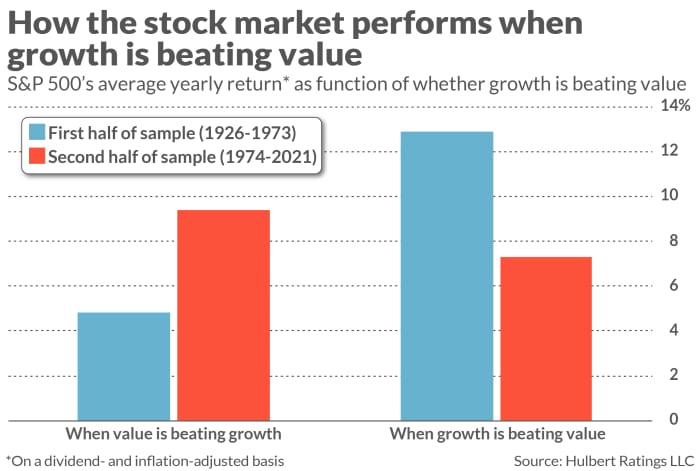

This is illustrated in the chart above. It breaks the data into two equal-sized groups — the first encompassing the 1926-1973 period, and the second the period from 1974 until now. In the first half of the sample the stock market did better when growth was beating value. It was just the reverse in the second half of the sample.

My hunch as to why there is an inconsistent correlation between the market and value’s relative strength against growth: There’s more than one reason why growth can slip behind value. The strength of the economy is but one reason. Another, which has become particularly relevant in recent decades, is a bubble in growth-stock valuations. If such a bubble deflates, growth stocks can seriously lag value stocks even while the overall economy continues to grow.

We saw some of this during the deflation of the internet bubble between March 2000 and October 2002. Though that bear market lasted two-and-a-half years, the associated recession lasted just eight months (from March to November 2001, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the semi-official arbiter of when recessions begin and end). At the end of that bear market, U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) was 10% higher than where it stood at the beginning. Yet the S&P 500 was 49.1% lower. Much of that difference can be chalked up to growth stock valuations coming back to earth.

Value stocks performed quite well during that bear market, in relative terms. Furthermore, according to French’s data, the average small-cap value stock actually made money during that bear market.

The bottom line? Relax. While much is riding on whether the value style has embarked on a several-year period of outperforming growth, the fate of the bull market is not one of them.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: Why stock market bulls may be right to push valuations so high

Plus: Not every stock is in a bubble. Here’s how to find today’s bargains and tomorrow’s winners