Delta blamed for poor jobs report, but too few people willing to work might be a bigger problem

President Biden blamed the coronavirus delta variant for the paltry number of jobs created in August, but the real culprit might be a shortage of people willing to work.

The government on Friday said the economy created 235,000 new jobs last month, just one-third of Wall Street’s DJIA,

The tepid report raised questions about whether the U.S. recovery has been taken down a peg and when the Federal Reserve finally starts to wean the economy off its easy money-strategy.

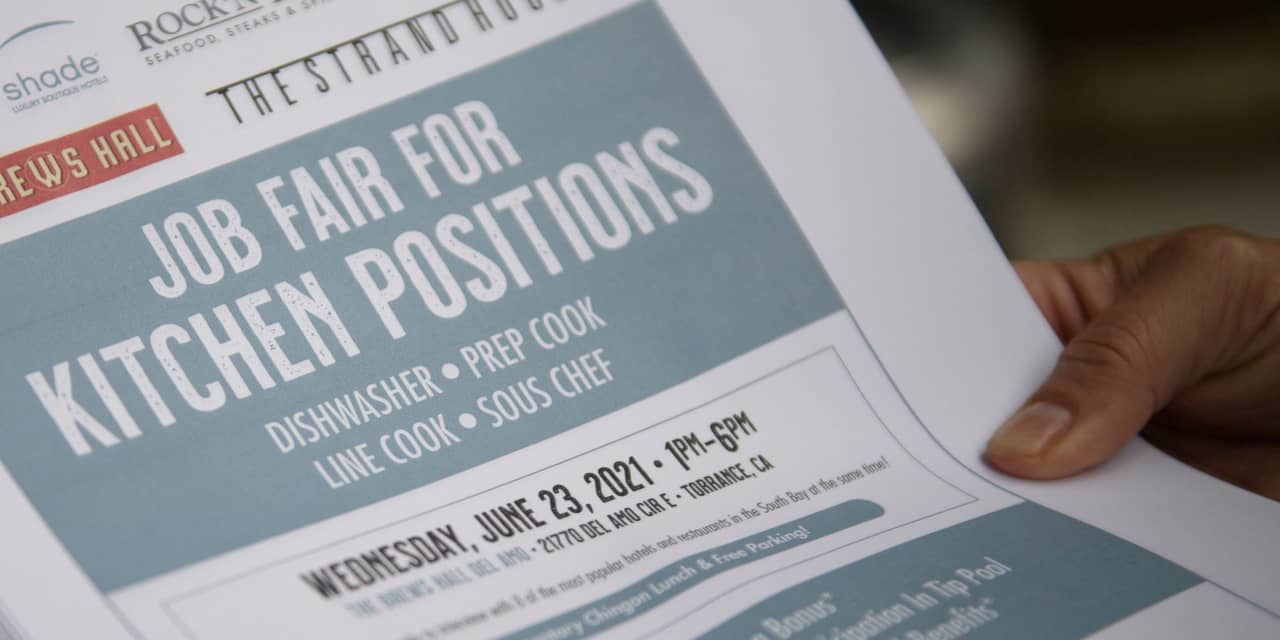

At first glance, the delta variant appeared to be the guilty party. After all, virus-sensitive leisure and hospitality businesses added zero new jobs in August. These companies had boosted employment by an average of 364,000 a month in the prior four months.

See: MarketWatch Economic Calendar

Hotel, restaurants, theaters and other service businesses, the thinking goes, cut back on hiring as delta cases surged and customers stayed away. Other evidence that supports this argument: A decline in flying, hotel bookings and restaurant reservations.

“There’s no question the delta variant is why today’s jobs report isn’t stronger,” Biden said at the White House on Friday.

Yet other clues suggest the virus was a smaller factor.

Consider a pair of ISM surveys of senior executives at America’s largest companies. Few cited delta directly for a slowdown in business in August. Instead they blamed persistent shortages of labor and supplies.

They’ve got plenty of demand, in other words, and more than enough orders to keep the economy humming. What they can’t get enough of is workers or materials to produce as much as they are able to sell.

“We are hiring at record levels to staff our restaurants, but turnover is high, and many former employees are still on extended unemployment or not ready to return to work,” one executive told ISM.

Added another: “[It’s] increasingly difficult to find qualified candidates to fill open positions.”

Read: ‘People just aren’t applying’: Why the restaurant industry created no new jobs last month

The ISM business surveys are a “sign that the delta variant might not be hitting the economy quite as hard as the disappointing gain in non-farm payrolls suggested,” said chief US economist Paul Ashworth of Capital Economics.

Here’s another hint. Hourly worker pay surged again in August and wages have jumped 4.3% over the past year, the biggest increase since 2008 if the early days of the pandemic are excluded.

Soaring pay clearly shows businesses are still trying to hire workers — or paying existing employees more so they don’t leave for a higher-paying job elsewhere. Americans have been quitting at record levels to pursue other opportunities.

How can it be that the U.S. has a labor shortage when job openings are at a record high and millions of people aren’t working?

The government said 8. 4 million people were classified as unemployed in August. Another 5.7 million who aren’t in the labor force said they would like a job. That’s more than 14 million potential workers.

The labor shortage is a big puzzle for economists, but some of the pieces are well known.

For one thing, millions of people are still collecting unemployment benefits that in many cases pay more than their old jobs did. That’s because the federal government is temporarily doling out extra money to the unemployed during the pandemic.

Other surveys show that several million people who were close to retirement age left the workforce during the pandemic. Many probably aren’t coming back.

Some unemployed Americans, meanwhile, said they had enough money to get by or lived with a working spouse with a good salary. Still others either had to care for young children or were too scared of the virus to go back to work, though it was unclear how they are making ends meet.

“The huge labor shortage should have been a major warning sign that the lack of workers is restraining hiring and until the supply increases, there are only so many people that can be hired,” said Joel Naroff of Naroff Economic Advisors.

When will the supply of workers increase?

Perhaps as early as this month. The extra federal benefits expire on Monday, though the Biden White House has told states they can keep paying them through other stimulus programs.

If public schools reopen and stay open, that would also give unemployed parents more leeway to seek out a job.

Some retirees could also be drawn back into the labor force, but probably only if companies sharply increase pay.

The upshot is, the U.S. could suffer a labor shortage for months or even longer. There’s plenty of jobs out there, but simply not enough people to fill them.

“There are ample signs,” said chief economist Stephen Stanley of Amherst Pierpont Securities, “that the labor market remains drum-tight at the moment.”