Being a contrarian on inflation

It’s getting more difficult to argue—as I did four months ago—that inflation’s recent spike is transitory.

One measure of inflation—the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) index—was reported on Oct. 1 to have climbed in August by a greater-than-forecast 0.4%. Over the last 12 months the PCE index has risen at a 4.3% rate, the highest since 1991.

Even Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, who up until now has been squarely in the “transitory” camp, conceded this week that supply chain bottlenecks will keep inflation higher and for longer than he originally anticipated. “It’s frustrating to see the supply chain problems not getting better, in fact they are probably getting worse,” he said.

Given that inflation is probably the biggest single threat to retirees’ financial security, I am revisiting the argument I advanced four months ago.

I based it, you may recall, on an inflation prediction model that I had found to have the best track record over the last two decades at predicting inflation. This is the model created and maintained by the Cleveland Federal Reserve. I had compared its predictions with those of the University of Michigan’s consumer survey of inflation expectations, as well as of the breakeven inflation rate (the yield difference between nominal Treasuries and TIPS of similar maturities).

The last four months don’t alter the conclusion I reached then. The Cleveland Federal Reserve’s model still has a better track record than either of those other two. That’s why I believe it still makes sense to bet that inflation’s recent spike will be “transitory.”

What does the Cleveland Fed model say today? Despite inflation’s surprisingly large spikes over the last couple of months, its projections have barely budged. Four months ago, it was projecting that CPI inflation would average just 1.58% annualized over the subsequent 10 years. Their latest projection is barely higher at 1.63%.

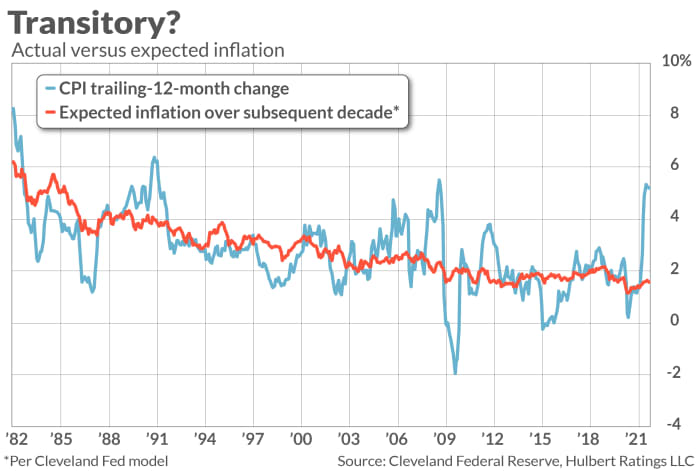

So the model is sticking to its guns that inflation will be modest in coming years—below the Fed’s 2% target, in fact. Take a close look at the accompanying chart, which plots the CPI’s trailing 12-month rate of change for each month since 1982, along with the inflation projections in each of those months from the Cleveland Fed model. Notice that the CPI is quite volatile compared to the projections from the Cleveland Fed model. When the CPI’s 12-month change has spiked well above or below the model’s projections, it has almost always quickly reverted.

My bet is that it will do so again in coming months.

Why is the Cleveland Fed model superior?

A full discussion of the methodology underlying the Cleveland Fed’s model is beyond the scope of this column. Interested readers should refer to research conducted by economists at that bank. The model has a number of inputs, including Treasury yields, surveys of professional forecasters, and inflation swaps—which are derivatives in which one party to the transaction agrees to swap fixed payments in return for payments tied to the inflation rate.

Why does the model work better than the breakeven inflation rate? As two Cleveland Fed economists explain: “Because people don’t like the risk associated with inflation, they pay less for a nominal, unprotected bond, which means it has a higher interest rate. Thus the difference between nominal bonds and TIPS overstates the expected inflation rate.”

This helps us to understand the current difference between the Cleveland Fed model and the breakeven rate. The Cleveland Fed’s model calculates expected inflation over the next decade to be 1.63%, while the 10-year breakeven rate is 2.37%. That difference of 74 basis points may have nothing to do with expected inflation but instead be the compensation that investors require in order to incur the risk that inflation could be much worse than expected.

Why does the University of Michigan survey perform less well than the Cleveland model? My hunch is that it’s because consumers are primarily reactive when it comes to inflation expectations, simply extrapolating the recent past into the future. So when inflation is low, as it was in the spring and summer of last year as the Covid19-induced lockdowns impacted the economy, consumers expect inflation to stay low. And now that the CPI has spiked higher, they are expecting inflation to be much higher.

Such extrapolation isn’t helpful, however, since (as we saw from the accompanying chart) the CPI’s short-term gyrations in recent decades have tended to revert rather than continue. This is why, as I reported four months ago, the University of Michigan survey of inflation expectations is inversely correlated with inflation’s subsequent trends.

The bottom line? Be skeptical of the “high inflation is here to stay” arguments that are increasingly dominating the financial media. Though anything is possible, the message of one of the models with the best track records continues to be that inflation’s recent spike is transitory.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at [email protected].