How does Biden’s latest plan to tax the superrich work? ‘It’s more straightforward.’

As President Joe Biden tries to sew up a deal on a stripped-down $1.75 trillion spending bill to strengthen the social safety net, he’s proposed a “surtax” on multimillionaires and billionaires in his newest effort to boost tax receipts from America’s wealthiest.

Under the plan unveiled Thursday, the highest-end households would face a 5% added tax for income above $10 million, and, once income reaches $25 million, they’d pay an 8% added tax, according to a White House announcement. These surtaxes would generate $230 billion in revenue, according to White House estimates.

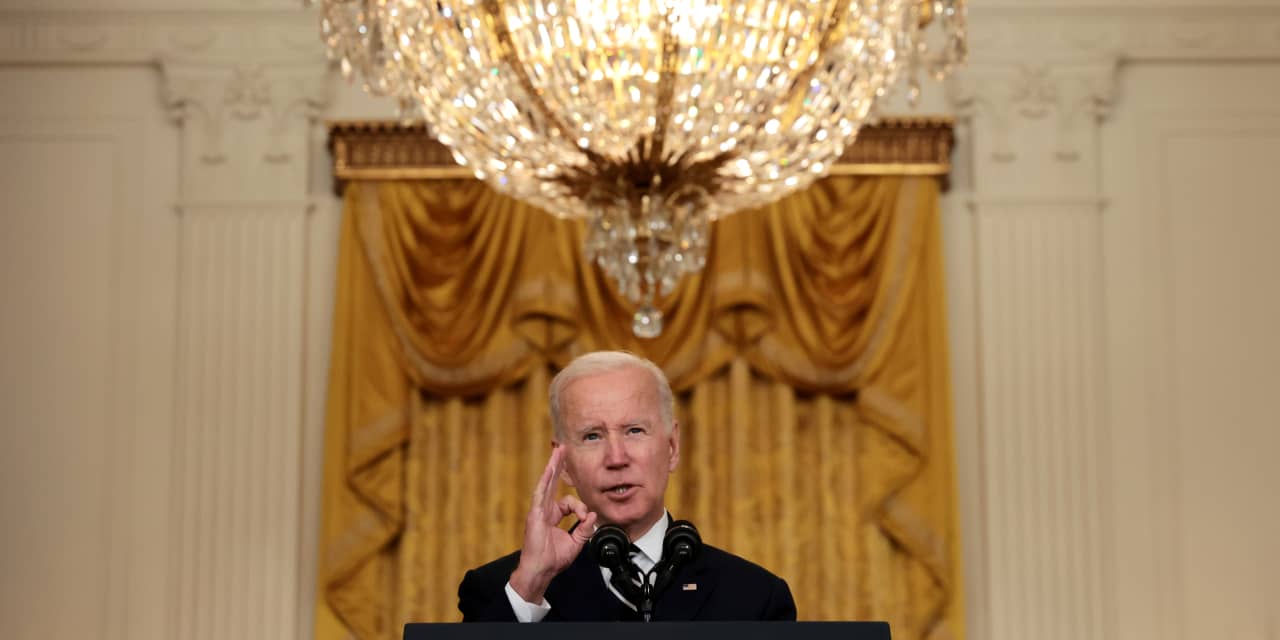

“All I’m asking is: Pay your fair share. Pay your fair share. Pay your fair share. And right now, many of them are paying virtually nothing,” Biden said in a Thursday speech.

Of course, what any politician views as a fair share of taxes is “entirely subjective,” according to Kyle Pomerleau, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a right-leaning think tank.

But here’s what is clear: The very highest earners making at least $10 million could face a 45.8% combined statutory rate, and those with at least $25 million could face a 48.8% rate, Pomerleau said.

The top personal income-tax rate is 37%. Now factor in the 5% or 8% surtax, as well as changes to 3.8% tax that comes either from the net investment income tax or payroll taxes.

That’s just the federal income tax. Don’t forget the state and local income taxes that may apply. For example, New York and New Jersey within the past 12 months have been raising and broadening the top tax rate to bring in more money from the upper reaches of the upper class. Barring any changes from Congress, the top federal rate reverts back to 39.6% in 2026 once the temporary rate changes under the Trump-era tax-code overhaul of 2017 expire.

Don’t miss: Lifting of cap on SALT deductions is not in Biden’s reconciliation-bill framework — for now, that is

In the not-too-distant past, the superrich were readying for income and capital-gains rate hikes during the Biden administration. But as the White House tried to cobble consensus with no room for “no” votes, those proposed rate hikes hit rocky terrain.

Then this week came a “billionaire income tax” that, among other things, would have annually taxed the unsold portfolios of the superwealthy. That idea also ended up getting sidelined; some observers said the proposal on unrealized capital gains was an “untested” idea with too many open questions on implementation.

Enter the surtax. Or, more accurately, re-enter the surtax.

In September, the Ways and Means Committee unveiled a tax-hike proposal that, among other things, called for a 3% surtax on household making at least $5 million.

“Our plan looks better every day,” Rep. Richard Neal, chairman of the tax-writing House Ways and Means Committee, said earlier this week.

Compared with the proposal for taxing unrealized gains, Pomerleau said the surtax is “more straightforward,” adding: “It’s simpler.”

The surtax, as Pomerleau said he understands it, would apply to adjusted gross income. The sum on adjusted gross income is the number that applies before standard deductions and itemized deductions nip away at the money Uncle Sam can tax.

Rep. Don Beyer, a Democrat from Virginia, introduced the original form of the millionaire surtax back in 2019 with Sen. Chris Van Hollen, a fellow Democrat from Maryland. “Our idea of a surtax has an elegant simplicity, capturing all income without loopholes or carveouts for the rich, and it only affects the very wealthy, raising billions we always hoped would be spent on priorities like early child care, health care, and fighting climate change,” Beyer said Thursday in a statement.

But is this a wealth tax?

No, it’s not a wealth tax but a type of income tax, according to Pomerleau. “It’s not taxing any fair-market value of assets, minus liability,” he said.

At a certain level, it may not be a formal wealth tax, said David Herzig, a tax principal with Ernst & Young’s Private Client Services Tax practice. “I don’t know if it matters if you call it a wealth tax or not,” he said, later adding, “It’s a tax on wealthy income earners, but it’s not a tax on accumulated wealth.”

The debate over more taxes for the rich has been driven by the view among Democrats that the wealthy pay too little, using a tax code that’s tilted to their advantage.

Economist Gabriel Zucman, who helped advise Sen. Elizabeth Warren on her wealth-tax idea during the Massachusetts lawmaker’s presidential run in 2020, said on Twitter TWTR,

Owners of pass-through businesses, such as a partnership or a limited liability company, face individual income taxes, not corporate ones. But with a 21% corporate income-tax rate instead of a personal rate more than double the size, Zucman said “they will convert to become corporations, siphoning off the individual income-tax base.”

One way to shrink tax exposure at the top is the so-called buy, borrow, die approach to borrowing against the paper gains on unsold holdings and then passing on the appreciating assets to the next generation. Inheritors can then shrink their tax bill, because the cost basis resets when they receive the asset, like appreciating stock shares.

One way to ease the surtax’s bite, or avoid it altogether, is putting off capital asset sales that would ultimately bump up income, Pomerleau said.

Even with a surtax in place, the “buy, borrow, die” approach “would continue to be a relevant feature of the tax code,” Pomerleau said.