Where are the workers? Cutoff of U.S. jobless aid spurs no influx

Earlier this year, an insistent cry arose from business leaders and Republican governors: Cut off a $300-a-week federal supplement for unemployed Americans.

Many people, they argued, would then come off the sidelines and take the millions of jobs that employers were desperate to fill.

Yet three months after half the states began ending that federal payment, there’s been no significant influx of job seekers.

In states that cut off the $300 check, the workforce — the number of people who either have a job or are looking for one — has risen no more than it has in the states that maintained the payment.

That federal aid, along with two jobless aid programs that served gig workers and the long-term unemployed, ended nationally Sept. 6. Yet America’s overall workforce actually shrank that month.

“Policymakers were pinning too many hopes on ending unemployment insurance as a labor market boost,” said Fiona Greig, managing director of the JPMorgan Chase Institute, which used JPMorgan bank account data to study the issue. “The work disincentive effects were clearly small.”

Labor shortages have persisted longer than many economists expected, deepening a mystery at the heart of the job market.

Companies are eager to add workers and have posted a near-record number of available jobs. Unemployment remains elevated. The economy still has 5 million fewer jobs than it did before the pandemic. Yet job growth slowed in August and September.

An analysis of state-by-state data by The Associated Press found that workforces in the 25 states that maintained the $300 payment actually grew slightly more from May through September, according to data released Friday, than they did in the 25 states that cut off the payment early, most of them in June.

The $300-a-week federal check, on top of regular state jobless aid, meant that many of the unemployed received more in benefits than they earned at their old jobs.

An earlier study by Arindrajit Dube, an economist at University of Massachusetts, Amherst and several colleagues found that the states that cut off the $300 federal payment saw a small increase in the number of unemployed taking jobs. But it also found that it didn’t draw more people off the sidelines to look for work.

Economists point to a range of factors that are likely keeping millions of former recipients of federal jobless aid from returning to the workforce. Many Americans in public-facing jobs still fear contracting COVID-19, for example. Some families lack child care.

Other people, like Rachel Montgomery of Anderson, Indiana, have grown to cherish the opportunity to spend more time with their families and feel they can get by financially, at least for now.

Montgomery, a 37-year-old mother, said she has become much “pickier” about where she’s willing to work after having lost a catering job last year. Losing the $300-a-week federal payment hasn’t changed her mind. She’ll receive her regular state jobless aid for a few more weeks.

“Once you’ve stayed home with your kids and family like this, who wants to physically have to go back to work?” she said. “As I’m looking and looking, I’ve told myself that I’m not going to sacrifice pay or flexibility working remotely when I know I’m qualified to do certain things. But what that also means is that it’s taking longer to find those kinds of jobs.”

Indeed, the pandemic appears to have caused a re-evaluation of priorities, with some people deciding to spend more time with family and others insistent on working remotely or gaining more flexible hours.

Some former recipients, especially older, more affluent ones, have decided to retire earlier than they had planned. With Americans’ overall home values and stock portfolios having surged since the pandemic struck, Fed officials estimate that up to 2 million more people have retired since then than otherwise would have.

And after having received three stimulus checks in 18 months, plus federal jobless aid in some cases, most households have larger cash cushions than they did before the pandemic.

Greig and her colleagues at JPMorgan found in a study that the median bank balance for the poorest one-quarter of households has jumped 70% since COVID hit. A result is that some people are taking time to consider their options before rushing back into the job market.

Graham Berryman, a 44-year-old resident of Springfield, Missouri, has been living off savings since Missouri cut off the $300-a-week federal jobless payment in June. He has had temporary work reviewing documents for law firms in the past. But he hasn’t found anything permanent since August 2020.

“I’m not lazy,” Berryman said. “I am unemployed. That does not mean I’m lazy. Just because someone cannot find suitable work in their profession doesn’t mean they’re trash to be thrown away.”

Likewise, some couples have decided that they can get by with only one income, rather than two, at least temporarily.

Sarah Hamby of Kokomo, Indiana, lost her $300-a-week federal payment this summer after Gov. Eric Holcomb, a Republican, ended that benefit early. Hamby’s husband, who is 65, has kept his job working an overnight shift at a printing press throughout the pandemic. But he may decide to join the ranks of people retiring earlier than they’d planned.

And Hamby, 51, may do so herself if she doesn’t find work soon. The jobs she had for decades at auto factories have largely disappeared. The positions that she sees available now require skills she doesn’t have. Yet she isn’t desperate for just any job.

“I’m at a point where I feel too old to go off and get educated or trained to do other type of work,” she said. “And to be honest, I don’t want to go work at a computer, in an office, like what a lot of us are being pushed to do. So now I’m stuck between doing some line of work that pays too little for what it’s worth — or is too physically demanding — or I just don’t work.”

Nationally, the proportion of women who were either working or looking for work in September fell for a second straight month, evidence that many parents — mostly mothers — are still unable to manage their childcare duties to return to work.

Staffing at childcare centers has fallen, reducing the care that is available. And while schools have reopened for in-person learning, frequent closings because of COVID outbreaks have been disruptive for some working parents.

Exacerbating the labor shortfall, a record number of people quit their jobs in August, in some cases spurred by the prospect of higher pay elsewhere.

In Missouri, a group of businesses, still frustrated by labor shortages more than three months after the state cut off the $300-a-week federal jobless checks, paid for billboards in Springfield that said: “Get Off Your Butt!” and “Get. To. Work.”

The state has seen no growth in its workforce since ending emergency benefits.

“We don’t know where people are,” said Brad Parke, general manager of Greek Corner Screen Printing and Embroidery, who helped pay for the billboards. “Obviously, they’re not at work. Apparently, they’re at home.”

Richard von Glahn, policy director for Missouri Jobs With Justice, an advocacy group, suggested that many people on the sidelines of the job market want more benefits or the flexibility to care for children.

“People don’t want to go back” to the pre-pandemic job market, von Glahn said. “Employers have a role in creating a work environment and offering a package that provides workers the security they need.”

In Wyoming, fewer people are in the workforce now than when the state cut off all emergency jobless aid. Fear of contracting COVID-19 likely discouraged some people from seeking jobs, Wenlin Liu, chief economist at the state Economic Analysis Division, said last week.

Wyoming has one of the lowest vaccination rates in the country, he noted, and has been a COVID-19 hotspot since late summer. The surge in infections, Liu said, may be causing some parents to keep their children home.

State Rep. Landon Brown, a Republican, defended the cutoff of federal unemployment aid. “Wyoming,” Brown said, “is not interested in continuing to allow the federal government to keep people away from jobs, paying them as much to stay home in some cases as to go and get a job.”

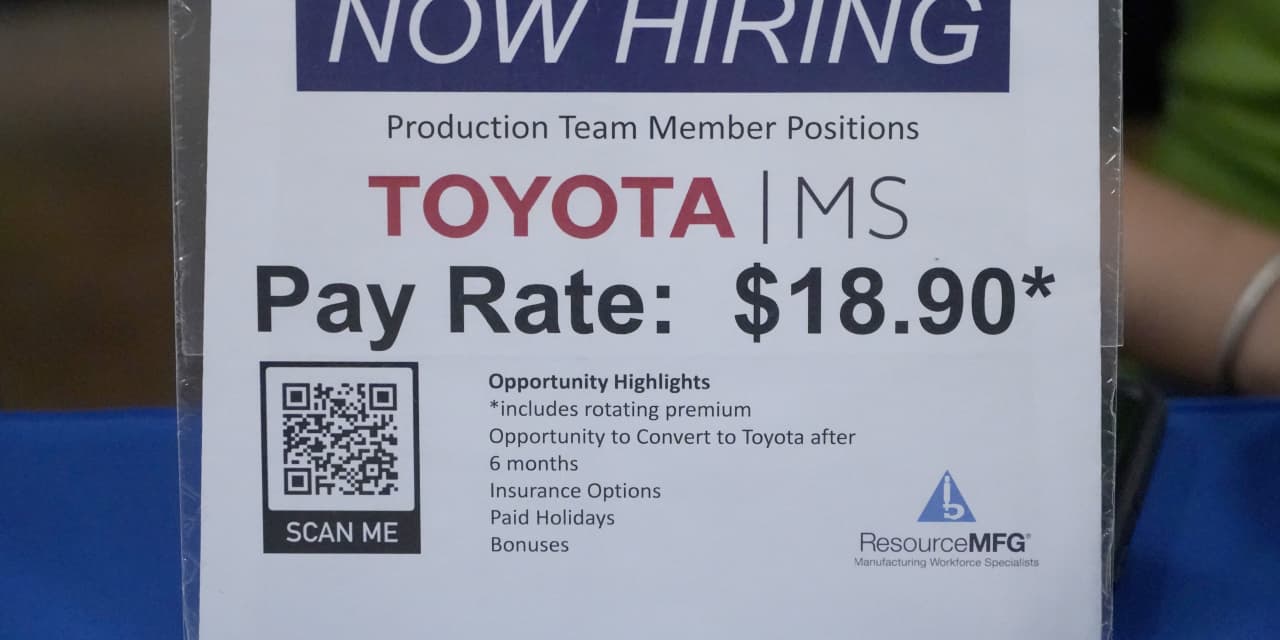

Mississippi ended all emergency jobless aid on June 12. Yet it had fewer people working in August than in May. In Tupelo last week, a job fair attracted 60 companies, including a recruiter from VT Halter Marine, a shipbuilder located 300 miles south. About 150 to 200 job seekers also attended, fewer than some businesses had hoped.

Adam Todd had organized the job fair for the Mississippi Department of Employment Security, which helps people find jobs and distributes unemployment benefits.

The agency has received “calls of desperation,” Todd said, “from businesses needing to recruit workers during the pandemic. “We’re in a different point in time than we have been in a very long time,” Todd said. “The job seeker is truly in the driver’s seat right now.”