Why California is shutting down its last nuclear plant

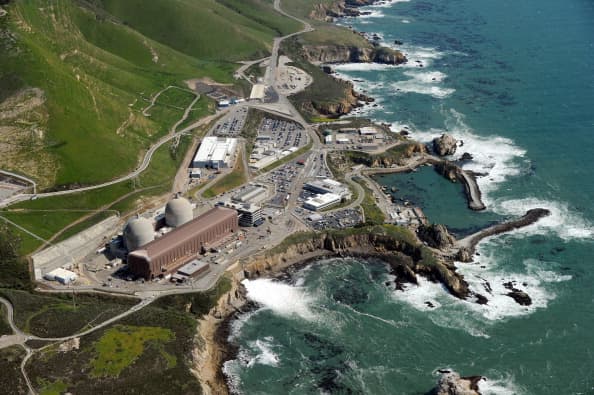

Aerial view of the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant which sits on the edge of the Pacific Ocean at Avila Beach in San Luis Obispo County, California on March 17, 2011.

Mark Ralston | AFP | Getty Images

California is not keeping up with the energy demands of its residents.

In August 2020, hundreds of thousands of California residents experienced rolling electricity blackouts during a heat wave that maxed out the state’s energy grid.

The California Independent System Operator issues flex alerts asking consumers to cut back on electricity usage and move electricity usage to off-peak hours, typically after 9 p.m. There were 5 flex alerts issued in 2020 and there have been 8 in 2021, according to CAISO records.

On Friday, Sept. 10, the U.S. Department of Energy granted the state an emergency order to allow natural gas power plants to operate without pollution restrictions so that California can meet its energy obligations. The order is in effect until Nov. 9.

At the same time, the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant, owned by Pacific Gas and Electric and located near Avila Beach in San Luis Obispo County, is in the middle of a decade-long decommissioning process that will take the state’s last nuclear power plant offline. The regulatory licenses for reactor Unit 1 and Unit 2, which commenced operation in 1984 and 1985 will expire in November 2024 and August 2025, respectively.

Diablo Canyon is the state’s only operating nuclear power plant; three others are in various stages of being decommissioned. The plant provides about 9% of California’s power, according to the California Energy Commission, compared with 37% from natural gas, 33% from renewables, 13.5% from hydropower, and 3% from coal.

Nuclear power is clean energy, meaning that the generation of power does not emit any greenhouse gas emissions, which cause global warming and climate change. Constructing a new power plant does result in carbon emissions, but operating a plant that is already built does not.

California is a strong advocate of clean energy. In 2018, the state passed a law requiring the state to operate with 100% zero-carbon electricity by 2045.

The picture is confusing: California is closing its last operating nuclear power plant, which is a source of clean power, as it faces an energy emergency and a mandate to eliminate carbon emissions.

Why?

The explanations vary depending on which of the stakeholders you ask. But underlying the statewide diplomatic chess is a deeply held anti-nuclear agenda in the state.

“The politics against nuclear power in California are more powerful and organized than the politics in favor of a climate policy,” David Victor, professor of innovation and public policy at the School of Global Policy and Strategy at UC San Diego, told CNBC.

Earthquake country

Diablo is located near several fault lines, cracks in the earth’s crust that are potential locations for earthquakes.

Concerns about nuclear plants and earthquakes grew after the 2011 disaster at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in Japan. On March 11, 2011, a 9.0-magnitude earthquake struck Japan, causing a 45-foot-high tsunami. Cooling systems failed and the plant released radioactive material in the area.

In July 2013, the then on-site Nuclear Regulatory Commission inspector for Diablo Canyon, Michael Peck, issued a report questioning whether the nuclear power plant should be shuttered while further investigation was done on fault lines near the plant. The confidential report was obtained and published by the Associated Press, and resulted in an extensive review process.

The Hosgri fault line, located about 3 miles away from Diablo Canyon, was discovered in the 1970s when construction was in early stages and the NRC was able to make changes to the research and construction plans. Peck’s filing brought attention to another collection of nearby fault lines — the Shoreline, Los Osos and San Luis Bay.

All of these discussions of safety are set against a backdrop of shifting sentiment about nuclear energy in the United States.

“Since Three Mile Island and then Chernobyl there has been a political swing against nuclear—since the late 1970s,” Victor told CNBC. “Analysts call this ‘dread risk’ — a risk that some people assign to a technology merely because it exists. When people have a ‘dread’ mental model of risk it doesn’t really matter what kind of objective analysis shows safety level. People fear it.”

SAN LUIS OBISPO, CALIFORNIA -JUNE 30: Anti nuclear supporters at Diablo Canyon anti-nuclear protest, June 30, 1979 in San Luis Obispo, California. (Photo by Getty Images/Bob Riha, Jr.)

Bob Riha Jr | Archive Photos | Getty Images

For citizens who live nearby, the fear is tangible.

“I’ve basically grown up here. I’ve been here all my adult life,” Heidi Harmon, the most recent mayor of San Luis Obispo, told CNBC.

“I have adult kids now, but especially after 9/11, my daughter, who was quite young then, was terrified of Diablo Canyon and became essentially obsessed and very anxious knowing that there was this potential security threat right here,” Harmon told CNBC.

In San Luis Obispo County, a network of loud sirens called the Early Warning System Sirens is in place to warn nearby residents if something bad is happening at the nuclear power plant. Those sirens are tested regularly, and hearing them is unsettling.

“That is a very clear reminder that we are living in the midst of a potentially incredibly dangerous nuclear power plant in which we will bear the burden of that nuclear waste for the rest of our lives,” Harmon says.

Also, Harmon doesn’t trust PG&E, the owner of Diablo Canyon, which has a spotted history. In 2019, the utility reached a $13.5 billion settlement to resolve legal claims that its equipment had caused various fires around the state, and in August 2020 it pleaded guilty to 84 counts of involuntary manslaughter stemming from a fire caused by a power line it had failed to repair.

“I know that PG&E does its level best to create safety at that plant,” Harmon told CNBC. “But we also see across the state, the lack of responsibility, and that has led to people’s deaths in other areas, especially with lines and fires,” she said.

Heidi Harmon, former mayor of San Luis Obispo

Photo courtesy Heidi Harmon

While living in the shadow of Diablo Canyon is scary, she is also well aware of the dangers of climate change.

“I’ve got an adult kid who was texting me in the middle of the night asking me if this is the apocalypse after the IPCC report came out, asking me if I have hope, asking me if it’s going to be okay. And I cannot tell my kid that it’s going to be okay, anymore,” Harmon told CNBC.

But PG&E is adamant that the plant is not shutting down because of safety concerns.

The utility has a team of geoscience professionals, the Long Term Seismic Program, who partner with independent seismic experts to ensure the facility remains safe, Suzanne Hosn, a spokesperson for PG&E, told CNBC.

The main entrance into the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power plant in San Luis Obispo, Calif., as seen on Tues. March 31, 2015.

Michael Macor | San Francisco Chronicle | Hearst Newspapers via Getty Images

“The seismic region around Diablo Canyon is one of the most studied and understood areas in the nation,” Hosn said. “The NRC’s oversight includes the ongoing assessment of Diablo Canyon’s seismic design, and the potential strength of nearby faults. The NRC continues to find the plant remains seismically safe.”

A former technical executive who helped operate the plant also vouched for its safety.

“The Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant is an incredible, marvel of technology, and has provided clean, affordable and reliable power to Californians for almost four decades with the capability to do it for another four decades,” Ed Halpin, who was the Chief Nuclear Officer of PG&E from 2012 until he retied in 2017, told CNBC.

“Diablo can run for 80 years,” Halpin told CNBC. “Its life is being cut short by at least 20 years and with a second license extension 40 years, or four decades.”

Local power-buying groups don’t want nuclear

PG&E offered a very different reason for closing Diablo Canyon when it set the wheels in motion in 2016.

According to legal documents PG&E submitted to the California Public Utilities Commission, the utility anticipated lower demand — not for energy in general, but for nuclear energy specifically.

One reason is a growing number of California residents buying power through local energy purchasing groups called community choice aggregators, the 2016 legal documents say. Many of those organizations simply refuse to buy nuclear.

There are 23 local CCAs in California serving more than 11 million customers. In 2010, less than 1% of California’s population had access to a CCA, according to a UCLA analysis published in October. That’s up to more than 30%, the report said.

The Redwood Coast Energy Authority, a CCA serving Humboldt County, strongly prefers renewable energy sources over nuclear, Executive Director Matthew Marshall told CNBC.

“Nuclear power is more expensive, it generates toxic waste that will persist and need to be stored for generations, and the facilities pose community and environmental risks associated with the potential for catastrophic accidents resulting from a natural disaster, equipment failure, human error, or terrorism,” said Marshall, who’s also the president of the trade association for all CCAs in California.

Consequently, the Redwood Coast Energy Authority has refused all power from Diablo Canyon.

There are financial factors at play, too. CCAs that have refused nuclear power stand to benefit financially when Diablo shuts down. That’s because they are currently paying a Power Charge Indifference Adjustmentfee for energy resources that were in the PG&E portfolio for the region before it switched over to a CCA. Once Diablo is gone, that fee will be reduced.

Meanwhile, CCAs are aggressively investing in renewable energy construction. Another CCA in California, Central Coast Community Energy, which also decided not to buy nuclear power from Diablo Canyon, has instead invested in new forms of energy.

PALM SPRINGS, CA – MARCH 27: Giant wind turbines are powered by strong winds in front of solar panels on March 27, 2013 in Palm Springs, California. According to reports, California continues to lead the nation in green technology and has the lowest greenhouse gas emissions per capita, even with a growing economy and population. (Photo by Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images)

Kevork Djansezian | Getty Images News | Getty Images

“As part of its energy portfolio in addition to solar and wind, CCCE is contracting for two baseload (available 24/7) geothermal projects and large scale battery storage which makes abundant daytime renewable energy dispatchable (available) during the peak evening hours,” said the organization’s CEO, Tom Habashi.

Technically, California’s 2018 clean energy law requires 60% of that zero-carbon energy come from renewables like wind and solar, and leaves room open for the remaining 40% to come from a variety of clean sources. But functionally, “other policies in California basically exclude new nuclear,” Victor told CNBC.

The utility can’t afford to ignore the local political will.

“In a regulated utility, the most important relationship you have is with your regulator. And so it’s the way the politics gets expressed,” Victor told CNBC. “It’s not like Facebook, where the company has protesters on the street, people are angry at it, but then it just continues doing what it was doing because it’s got shareholders and it’s making a ton of money. These are highly regulated firms. And so they’re much more exposed to politics of the state than you would think of as a normal firm.”

Cost uncertainty and momentum

Apart from declining demand for nuclear power, PG&E’s 2016 report also noted California’s state-wide focus on renewables, like wind and solar.

As the percentage of renewables continues to climb, PG&E reasoned, California will collect most of its energy when the sun shines, flooding the electricity grid with surges of power cyclically. At the times when the electricity grid is being turbocharged by solar power, the constant fixed supply of nuclear energy will actually become a financial handicap.

When California generates so much energy that it maxes out its grid capacity, prices of electricity become negative — utilities essentially have to pay other states to take that energy, but are willing to do so because it’s often cheaper than bringing energy plants offline. Although the state is facing well-publicized energy shortages now, that wasn’t the case in 2016.

PG&E also cited the cost to continue operating Diablo, including compliance with environmental laws in the state. For example, the plant was has a system called “once-through cooling,” which uses water from the Pacific Ocean to cool down its reactors. That means it has to pump warmed ocean water back out to the coastal waters near Diablo, which alarms local environmental groups.

Finally, once the wheels are in motion to shut a nuclear plant down, it’s expensive and complicated process to reverse.

Diablo was set on the path to be decommissioned in 2016 and will operate until 2025. Then, the fuel has to be removed from the site.

“For a plant that has been operational, deconstruction can’t really begin until the fuel is removed from the reactor and the pools, which takes a couple years at least,” Victor told CNBC. Only then can deconstruction begin.

Usually, it takes about a decade to bring a nuclear plant offline, Victor told CNBC, although that time is coming down.

“Dismantling a nuclear plant safely is almost as hard and as expensive as building one because the plant was designed to be indestructible,” he said.

Politics favor renewables

All of these factors combine with a political climate that is almost entirely focused on renewables.

In addition to his academic roles, Victor chairs the volunteer panel that is helping to oversee and steward the closing of another nuclear power plant in California at San Onofre. There, an expensive repair would have been necessary to renew the plant’s operating license, he said.

Kern County, CA – March 23: LADWPs Pine Tree Wind Farm and Solar Power Plant in the Tehachapi Mountains Tehachapi Mountains on Tuesday, March 23, 2021 in Kern County, CA.(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Irfan Khan | Los Angeles Times | Getty Images

“The situation of Diablo is in some sense more tragic, because in Diablo you have a plant that’s operating well,” Victor said. “A lot of increasingly politically powerful groups in California believe that [addressing climate change] can be done mainly or exclusively with renewable power. And there’s no real place for nuclear in that kind of world.”

The pro-nuclear constituents are still trying. For example, Californians for Green Nuclear Power is an advocacy organization working to promote Diablo Canyon to stay open, as is Mothers for Nuclear.

“It’s frustrating. It’s something that I’ve spent well in excess of 10,000 hours on this project pro bono,” said Gene Nelson, the legal assistant for the independent nonprofit Californians for Green Nuclear Power.

“But it’s so important to our future as a species — that’s why I’m making this investment. And we have other people that are making comparable investments of time, some at the legal level, and some in working on other policies,” Nelson said.

Even if California can eventually build enough renewables to meet the energy demands of the state, there are still unknowns, Victor said.

“The problem in the grid is not just the total volume of electricity that matters. It’s exactly when the power is available, and whether the power can be turned on and off exactly as needed to keep the grid stabilized,” he told CNBC. “And there, we don’t know.”

“It might be expensive. It might be difficult. It might be that we miss our targets,” Victor told CNBC. “Nobody really knows.”

For now, as California works to ramp up its renewable energy resources, it will depend on its ability to import power, said Mark Z. Jacobson, a professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Stanford. Historically, the state has imported hydropower from the Pacific Northwest and Canada, and other sources of power from across the West.

“California will be increasing renewable energy every year from now on,” Jacobson told CNBC. “Given California’s ability to import from out of state, there should not be shortfalls during the buildout.”