Greenland Minerals tanks as uranium ban leaves project in limbo

Greenland Minerals has previously said that while uranium was not of great economic significance to its project, revenues generated by the metal and other by-products would help offset rare earth production costs.

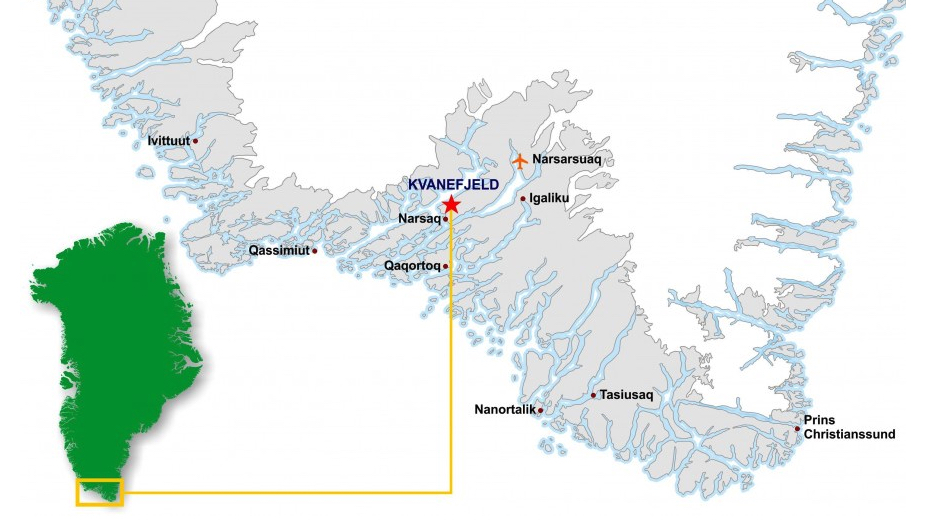

The company told shareholders on Friday that the company was now seeking advice on how the new legislation would impact the proposed development strategy for its Kvanefjeld.

It noted the ban would hamper exploration and production of key critical metals, including rare earths, which the world needs to switch to a greener economy and reduce carbon emissions.

“There are no active primary uranium projects in Greenland. Therefore, the legislation is directed at the production of rare earth materials and other critical metals, where it is common for ores to contain radioactive elements including uranium and thorium,” the company said in the statement.

It added that an independent radiological assessment of the project had concluded it was expected to release “only small amounts” of additional radioactivity to the environment, and was not expected to result in an adverse effect, or significant harm, to the region.

The new law bans exploration of deposits with a uranium concentration higher than 100 parts per million (ppm), which is considered very low-grade by the World Nuclear Association.

“The company is not aware of any technical, radiological, or health and safety reasons why the Greenland government has selected a threshold level of 100ppm uranium for the legislation,” Greenland Minerals said.

The company’s shares were placed in a trading halt on the Australian Securities Exchange on Wednesday, resuming after today’s announcement. They closed 29.6% lower on Friday, leaving the miner with a market capitalization of A$168 million ($123 million).

The stock has lost 52% of its value since April 6, when a coalition government, which consists of the Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA) and Naleraq parties, won the parliamentary election.

Beyond fishing

Greenland, a vast autonomous arctic territory that belongs to Denmark, bases its economy on fishing and subsidies from the Danish government.

As a result of melting ice in the poles, miners have become increasingly interested in the mineral-rich island, which has become a hot prospect for miners. They are seeking anything from copper and titanium to platinum and rare earths, which are needed for electric vehicle motors and the so-called green revolution.

Residents of the southern town of Narsaq, the closest village to Green Minerals’s project, have raised concerns about the impact that mining, and potential radioactive dust, would have on the area.

The community, already suffering the effects of climate change, doesn’t want to endure additional challenges so that the rest of the world can drive electric cars, local activist Mariane Paviasen, who ran for parliament under IA, told The New York Times in October.

(Image courtesy of Greenland Minerals.)

Greenland is currently home to two mines: one for anorthosite, whose deposits contain titanium, and one for rubies and pink sapphires.

Before the April election, the island had issued several exploration and mining licenses in a bid to diversify its economy and eventually realize its long-term goal of independence from Denmark.

The US government recently extended an economic aid package to Greenland as part of the Joe Biden administration’s efforts to ensure the supply of critical minerals, particularly rare earths, from outside China.

Former president Donald Trump offered to buy the Arctic island to help address Chinese dominance of the rare earths market.

China accounts for almost 80% of the global mined supply of the elements used in everything from hi-tech electronics to military equipment.

Greenland Minerals, while based in Australia, is a Chinese-owned exploration company. Shenghe Resources Holding, its largest shareholder, would process the ore extracted.