Interactive map, report show socio-environmental impacts of energy transition

“The World Bank estimates that more than 3 billion tons of metals and minerals could be required over the next 30 years to power the technologies for the global energy transition. Key critical metals and minerals include copper, lithium, graphite, cobalt, nickel, and rare earths,” the report reads. “The global mining industry, often supported by host governments, is positioning mining as a ‘green solution’ to the climate crisis. This ‘green mining boom’ is rapidly expanding into culturally and ecologically sensitive areas, increasingly affecting Indigenous and human rights, community livelihoods and the environment.”

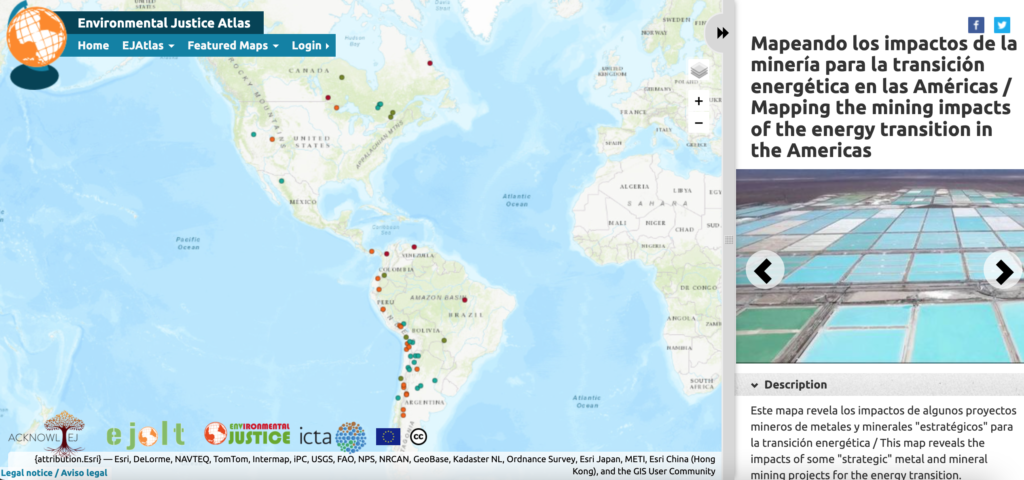

Since over 60% of global mining companies are registered in Canada, the dossier and map put special attention on the activities developed by Canadian miners but also of Australian firms operating in Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Mexico, the United States, and Canada.

The overall conclusion after examining the 25 cases, is that regardless of the commodity being exploited, large-scale mining generates intense impacts and is linked with a high number of socio-environmental conflicts, about 20% of the 3550 documented by the Environmental Justice Atlas.

“Mining projects are encroaching on more and more fragile and biodiverse ecosystems like the Amazon and the salares, without recognition of the rights of local communities who inhabit these territories,” the report states. “While companies are marketing these mines as ‘green,’ many mines are the same size and use the same techniques to extract minerals as the large-scale gold, silver, and copper mines that already exist on the continent.”

According to MiningWatch Canada and the Environmental Justice Atlas, projects are quickly expanding into the Ecuadorian Amazon and rainforests, glacial areas in Peru, the salt flats in Chile and other Ramsar-designated wetlands in Argentina and connected river systems — areas that play important roles in providing fresh water and sustaining flora and fauna.

“The environmental impacts of mining are felt much beyond the immediate area of the project, affecting entire regions through watersheds, placing biodiversity and species at risk of extreme harm and, in some cases, even extinction. Furthermore, resource extraction can harm the ecosystems that play an important role in regulating our global climate, such as the case with the Amazon,” the document states.

Through the mapping exercise, the NGOs also found mining — particularly for lithium — is already endangering the quality and quantity of water available to communities, particularly in places like Argentina.

“While communities face water emergencies, mining operations can exceed the daily water usage of the inhabitants of the region, putting further pressure on already-arid regions and putting at risk the availability of drinking water,” the dossier points out. “Mining is also a source of water pollution. To produce one ton of lithium in the salt flats in Atacama (Chile), 2,000 tons of water are evaporated, causing significant harm to both the availability of water and the quality of underground freshwater reserves.”

Finally, the report expresses concern over mine tailings and waste rock being stored or left at mine sites, particularly in places where there is a sustained decrease in the ore grades of mining deposits.

Among the cases that illustrate this, the map and report mention the proposed Authier lithium project in Quebec, Canada, which seeks to build a 1-kilometre long, 225-metre-deep open-pit mine and generate 60 million tons of mining waste. They also mention the proposed Sonora open-pit lithium mine in Mexico, which will generate 131 million tons of waste over the course of 20 years of production, with 25 million tons of wet tailings.

“We need to think critically about what this energy transition model means for fragile ecosystems and the people who depend on them,” Viviana Herrera Vargas, interim Latin America program coordinator for MiningWatch Canada, said in a media statement. “There are communities across the Americas pushing back against this capitalist extractivist model.”