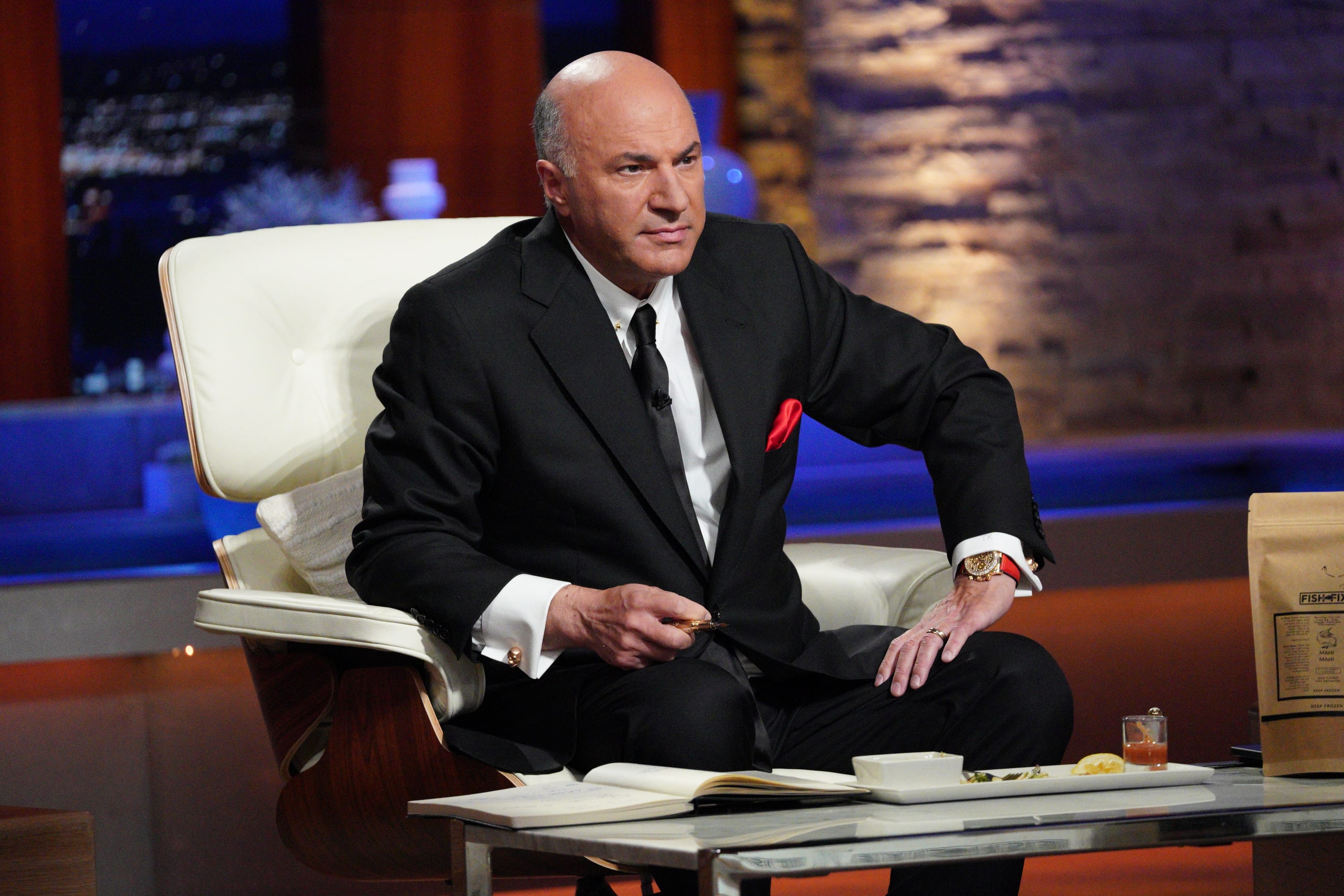

Christopher Willard | Disney General Entertainment Content | Getty Images

Some valuable firms like Hermes demonstrate there’s brand value preserved in keeping the business under family control. Others prove that the family connection can help restore belief in a damaged brand — Toyota after its unintended acceleration crisis in 2010 is an example.

But those cases are not typical.

For every family business that succeeds in transferring control from one generation to the next, there are likely to be multiple family businesses that fail as a result of mistakes in succession planning. One of the biggest mistakes of all made by successful first-generation founders, according to entrepreneur Kevin O’Leary, is when a family patriarch or matriarch assumes the right decision is to turn the business over to their children.

Given the number of family-controlled firms in the U.S. and around the world, it’s a big problem.

The majority of businesses in America are small and medium-sized private firms, and many were founded by a single entrepreneur and have been very successful, but O’Leary says when the business is in the family, it’s not just about the money, but the relationships.

“I’ve seen this happen in my own portfolio … it’s heartbreaking to see people in the same family tearing the family apart,” O’Leary said at a CNBC event in August.

This breakdown is most damaging when it comes to family succession, and often leads to the wealth generated by that founder being eroded over time.

“When businesses are wildly successful, it’s often because the founders, a mother or father, has tremendous operational skills, but those execution skills may not be present in the subsequent generation. That’s why we see American wealth evaporate within four generations,” O’Leary said.

Leadership experts who study family businesses, and people who grew up in them, say there’s truth in O’Leary’s warning about the unique dangers and emotionally-charged nature of family business succession planning.

“Great business leaders have learned to put infrastructure in place,” O’Leary said, whether that is from within their own family or, when the better option, from professional ranks.

This doesn’t mean children are denied access to family wealth or a say in preserving it, but they may lack the skill set to grow a business. The best founders, O’Leary said, know when the wise move is to put covenants in place to have professional managers oversee the business, while retaining board seats for children.

A prominent example from the U.S.: Berkshire Hathaway. Warren Buffett has not chosen one of his own children as a successor, but has had his son Howard on the company’s board for years and just recently added his daughter Susan to the board as well, not for operational decisions, but to retain the “culture.” Buffett’s son Peter is a director of the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation, which manages Warren Buffett’s charitable giving and is named after his late wife.

“All three of my children are devoted to maintaining the culture of the place,” Buffett told the Omaha World-Herald last week after the company’s most recent earnings report. “They have an unusual amount of devotion to that.”

O’Leary says that in the majority of cases he has seen, the same founders who say they are turning a business over to a child admit that the child doesn’t have the same skill set they had when founding the business.

“That’s how businesses lose all their value in just a few generations,” he said. “This is time proven. It’s history. Executional skills are really hard to find.”