Short-selling stocks — and trying to play short squeezes — can be very dangerous

Investing and trading are two completely different activities. If you are new to either or haven’t delved into the mechanics of short-selling, it’s important to understand how this type of high-stakes trading can influence stock prices, even if you have no intention of doing it yourself.

Shorting a stock is one of the riskiest things you can do as an investor. But the meme-stock craze — essentially playing the other side of short trades — can be nearly as risky because of the wild swings in share prices.

First, some definitions. In this article, investing means buying something and holding it, hoping that it goes up in value, that it provides income or both. Trading is buying and selling frequently to book gains.

If you buy a stock, you have only risked the amount you invested. The stock can go to zero and you can lose 100% of the money you invested.

If you short-sell a stock, you are betting that the price will go down and there is no limit on your potential losses if the share price rises unexpectedly. This is not to say your loss potential is unlimited — your broker will limit your losses by demanding more collateral to ensure you can cover those losses.

The mechanics of shorting a stock

Short-selling a stock is when you borrow shares of a company and sell them immediately because you expect the price to drop, after which you can repurchase the shares, return them to the lender and pocket the difference. It is a specialized strategy for some professional investors and traders but for individuals, it can be very risky and for more than one reason.

Some professionals have profited from highly publicized bets against companies they felt were in poor financial condition. Some have even alleged that corporate management teams have misled investors through inflated claims about their products or services.

For example, shortseller Hindenburg Research’s claims that Nikola Corp. NKLA,

The above definition of short-selling is simple, but the devil is in the details, which will follow after some more definitions:

Having a long position in a stock means you own the shares and expect (or hope) they go up in price.

Covering is when someone with a short position buys back the shares, to end the short trade and return them to the seller. The short-seller hopes to cover after the share price declines and book a profit. But the short-seller may also cover to limit losses if the price has gone up.

Margin is the amount of money an investor (or trader) has borrowed from their broker. You can set up a margin account with your broker to buy shares essentially on credit as well as to short a stock, in both cases with a limit set by the broker. If you are betting that the stock price will go down but it instead goes up, you may need to put up more collateral to maintain the agreed-upon margin. Otherwise the broker will begin selling your securities.

This brings us to our final definition: A short squeeze takes place when many investors looking to cover short positions start buying a stock at the same time. The resulting feeding frenzy pushes the share price higher, compelling more traders with short positions to cover, and so on. This can happen to any trader, and if you have a large portion of your risk concentrated in one short position, you can lose your shirt.

Shorting is best left to the professionals

One reason why the deck is stacked against an individual short-seller is that they cannot mitigate their risk by offsetting a large number of short positions with a large number of long positions.

A professional short-seller might have dozens of long positions offsetting a large number of short positions — both based on their own extensive research. They expect to get some trades wrong, but with the risk spread out, as well as their own triggers for when to cover, the overall risk to the pro manager from any one short squeeze may be relatively small.

And if you short a stock, there is the risk of a slow (or fast) bleed as you wait for a stock to go down enough for you to make your desired profit. For example, at one point in August 2021, shares of electric vehicle manufacturer Workhorse Group WKHS,

At that time, it cost 6% annually to borrow shares of Workhorse from a broker, according to one portfolio manager. That may not seem to be very much, but if that stock had gone up after you shorted it say, 14%, then you would be paying 20% a year for the privilege of making a risky trade.

Trying to time short-squeezes — the meme-stock craze

Let’s turn to a real example of short-selling and short squeezes. Professional traders had been shorting shares of videogame retailer GameStop GME,

Short interest in GameStop was higher than 100% through most of January, according to data provided by FactSet. Short interest in AMC Entertainment reached 57.81%.

Pros consider short interest above 30% to 40% to be dangerously high. Not only do high short percentages make it very expensive to borrow the shares but they create hair triggers for short squeezes. And that’s what happened, with shares of both GameStop and AMC Entertainment going on roller-coaster rides.

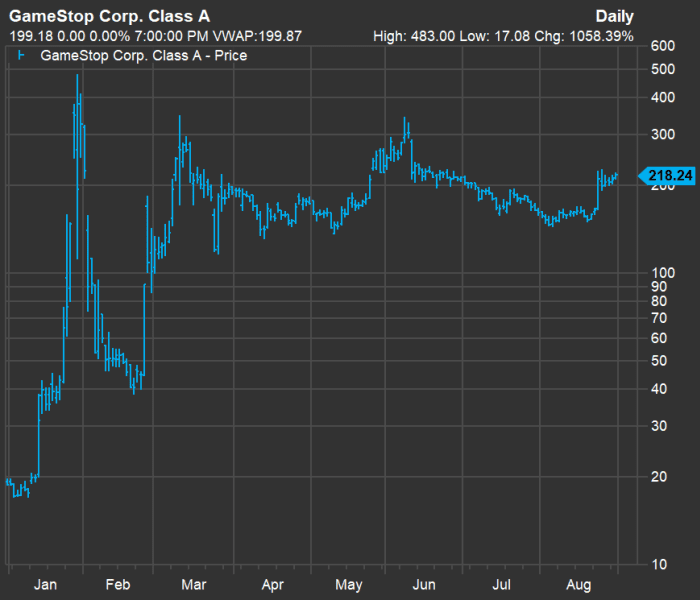

To be sure, the squeezes worked for traders who got in and out at the right times. It wasn’t so neat for others. This chart shows GameStop’s stock price for the first eight months of 2021.

The share of short interest for both stocks has since fallen sharply, making another short squeeze far less likely. The business prospects for both continue to look poor, especially relative to the broader stock market. Then again, both companies have taken advantage of the new interest among traders by issuing more shares to raise cash that could enable them to transform their businesses into healthier models.

The bottom line is that shorting individual stocks can be very risky. If you cut this risk by shorting many stocks for particular reasons while offsetting those shorts with long positions and monitoring all positions continually, you won’t have time for much else — you will be a professional trader.

Become a better investor by subscribing to MarketWatch newsletters.