Stocks are money makers now but be aware that some investors still haven’t recovered from the 2000 internet bubble

How many years of lagging stock portfolio returns would you tolerate in order to avoid the bursting of a stock market bubble?

That in effect is what Wall Street’s “permabears” are asking. They’ve been bearish on U.S. stocks for a number of years now, and therefore they (and their clients) have missed out on one of the most powerful bull markets in U.S. history.

Jeremy Grantham is one of the most prominent permabear; he is co-founder of Grantham, Mayo, & van Otterloo, a Boston-based asset management firm that is commonly known by the acronym GMO. Grantham has a number of impressive market calls to his credit, including largely sidestepping the bursting of both the internet bubble and the Great Recession. But he is not always bearish. In March 2009, the month in which the Great Financial Crisis-induced bear market came to an end, Grantham surprised many on Wall Street by penning a letter imploring managers to develop a plan for getting back into stocks.

Yet in most financial circles, in which a “what have you done for me lately” attitude prevails, Grantham is known for failing to anticipate the past decade’s bull market. Back in 2010, barely a year after the U.S. bull market began in March 2009, GMO projected that U.S. large-cap stocks would barely outperform inflation over the subsequent seven years.

As we now know, of course, U.S. stocks in recent years have been beating inflation by historic margins. Since 2010, the S&P 500’s SPX,

GMO’s response, in effect, is that caution could be vindicated and it would get the last laugh. In a recent analysis entitled “Wounds That Never Heal,” GMO argues that all it would take would be something similar to the bursting of the internet bubble in March 2000 or the bear market that accompanied the stagflation era of the 1970s.

Since this response is self-serving on GMO’s part, I decided to independently measure the long-term impact of living through the bursting of a bubble. What I found is sobering indeed. There have been occasions in U.S. stock market history—not as infrequent as we would like — when unlucky investors lost so much that it took a generation or more to recover.

If Grantham is right that the current stock market is forming a bubble that is about to burst, he’s also right that “for the majority of investors today, this could very well be the most important event of your investing lives.”

The 6% solution

One way of measuring the lingering effect of a bubble bursting is to calculate how long it takes for the stock market to make it back to its long-term trend line. Since 1793, according to research from Edward McQuarrie, an emeritus professor at Santa Clara University’s Leavey School of Business, the U.S. stock market has produced an inflation-adjusted total return of 6.05% annualized. For illustration purposes, I’ll round that to six percent.

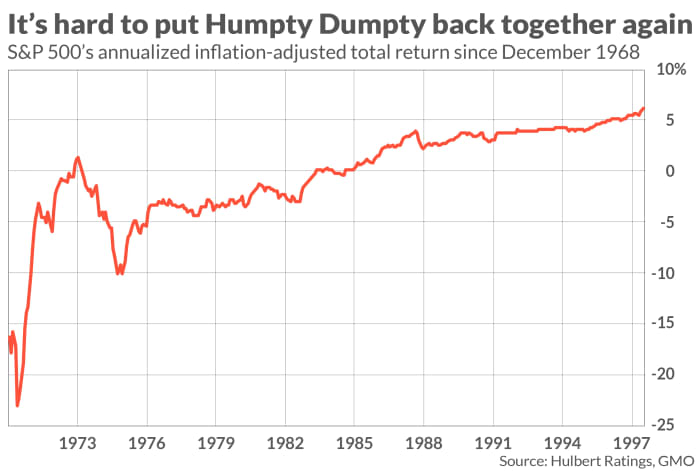

Imagine an investor in December 1968 to construct a portfolio that would financially support his retirement. His financial planner almost certainly would have turned to history to calculate this portfolio’s expected return, and so would have projected that — year-to-year volatility aside — the equity portion of his portfolio would produce a 6% annualized real total return over the subsequent decades.

I picked December 1968 to illustrate my point, as that marked a generational high. The chart below plots this investor’s annualized inflation-adjusted total return from that month forward. You can see the devastation wrought by the 1973-74 bear market, as well as the high-inflation years of the 1970s and early 1980s. But, most of all, notice that it’s not until mid-1997 that this investor’s long-term return would make it back to 6% annualized. That’s almost 30 years.

You might wonder why I didn’t focus on the bursting of the internet bubble in March 2000. The answer is that an investor unlucky enough to put a lump sum into the market at that time still hasn’t sufficiently recovered from losses so as to make it back to the 6% trendline. That investor’s real total-return since that date is 5.1% annualized. So 21 years have not been enough to vindicate the investor in March 2000 who based his financial future on extrapolating the long-term past.

Who believes in 6% anymore?

You also could object to the sobering message of my analysis on the grounds that no one expects the stock market to produce a long-term real total return of 6% annualized. In the low-interest-rate low-growth world in which we now live, you could argue, it’s unrealistic to expect the stock market’s future return to be as impressive as in the past.

Old beliefs die hard, however. You’d be surprised to learn that many financial planners continue to construct financial plans for their clients on the assumption (implicit if not explicit) that the future is like the past. It’s also the implicit assumption behind the glide paths followed by many of the target-date retirement funds that are so popular for 401(k) investors and retirees.

Nevertheless, your objection is not unfair. So it’s also worth focusing on how long investors need to merely break even following the bursting of a bubble.

Fortunately, the heavy lifting of such calculations has been conducted by McQuarrie. For the period dating back to 1793, he calculated the longest stretch in which the stock market’s inflation-adjusted total return was less than 1% annualized. The longest was the period beginning with the 1929 crash: From then until 1949, the stock market produced an inflation-adjusted total return of 0.75% annualized — 20 years, in other words.

That’s better than the nearly 30 years it took after an unlucky investor in December 1968 to make it back to the 6% trendline, but not by much.

Bubble trouble?

None of this sheds light on whether we are in a bubble, of course. All this discussion does is show that being cautious for a decade is not automatic grounds for concluding that the adviser has failed his clients.

The arguments for why the stock market is extremely overvalued, if not in a bubble, are familiar, and I won’t repeat them here. But given Grantham’s record at detecting prior bubbles, and given the long-term damage a bubble bursting would have on our portfolios, I would be nervous dismissing his caution out of hand.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at [email protected]