Look for the best dividend-paying stocks to stay in the money in 2022 and beyond

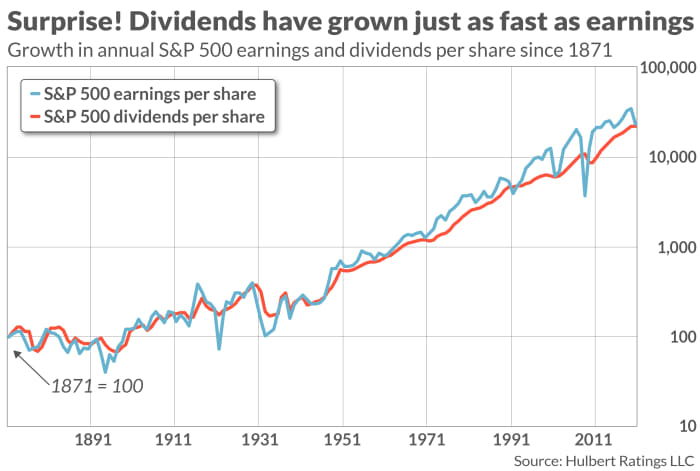

If dividends were an asset class, their risk-adjusted return would be better than almost any other. That’s because they tend to grow just as fast as corporate earnings, if not faster, and yet have far less volatility. That’s a winning combination

In fact, dividend-growth rates compare favorably to earnings-growth rates. The data don’t lie: Since 1871, according to data from Yale University’s Robert Shiller, the S&P 500’s SPX,

Don’t try to dismiss dividends’ robust growth rate on the grounds that it traces largely to the early years in Shiller’s 150-year database. That conjecture might otherwise seem plausible, since share repurchase activity is a relatively recent phenomenon and buybacks reduce the amounts companies would otherwise pay out as dividends. In fact, however, total DPS for S&P 500 companies have grown over the last 20 years at twice the pace of EPS: 6.6% annualized vs. 3.2%.

A similar story is told by the volatility of DPS’ and EPS’ growth rates. Since 1871, the standard deviation of the S&P 500’s DPS calendar-year growth rates has been a third of what it is for EPS growth rates — 11.9% vs. 32.6%. Dividends’ volatility advantage is even greater over the past 20 years: 8.5% vs. 61.1%.

Dividends vs. the 10-year Treasury

To illustrate the investment implications of these dividend characteristics, contrast the risks and rewards of investing in dividend-paying stocks and the U.S. 10-year Treasury TMUBMUSD10Y,

Let’s assume that you allocate $100,000 to each of these two investments. The 10-year Treasury at 1.53% will pay you $15,300 of interest over the next decade. In contrast, even assuming the dividend payers as a group don’t increase their dividends, they will pay almost $25,000 in dividends over the next 10 years. The dividend-paying stocks come out even further ahead if their dividends grow over the next decade.

Of course, with the 10-year Treasury you’re guaranteed to get back your $100,000 in 10 years’ time (assuming the U.S. government doesn’t default). With dividend-paying stocks, in contrast, there is no such guarantee. Nevertheless, those stocks would have to decline significantly in order for you not to still come out ahead of the Treasury note.

What’s the breakeven point, below which you would be better off with the Treasury? Assuming no growth in dividends over the next decade, your $100,000 investment in dividend stocks could decline to $85,600 and you would still be no worse off than you would have been with the 10-year Treasury. That’s equivalent to a loss over the next 10 years of 1.54% annualized.

How likely is it that dividend-paying stocks would perform worse than that? To find out, I analyzed the price-only returns of dividend stocks back to 1927, courtesy of the database maintained by Dartmouth professor Ken French. Specifically, I focused on a portfolio that each year contained the 30% of stocks with the highest dividend-yielding stocks. In only 6.8% of the rolling 10-year periods since 1927 did this portfolio perform worse than minus 1.54% annualized.

Though this 6.8% figure is already quite low, it exaggerates the true risk of high-quality dividend-paying stocks lagging the total return of the 10-year Treasury. That’s because French’s hypothetical portfolio was constructed on the basis of dividend yield alone, and therefore included some very risky high-yield stocks that eventually crashed and burned.

The bottom line? Equities in general are overvalued right now, as I argued recently. But high-quality dividend-paying stocks, relative to bonds, appear to still offer a compelling value proposition.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com