Powell Says Balance-Sheet Debate Underway, But This Time Is Different

(Bloomberg) — Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said officials have begun to debate when to start shrinking the central bank’s massive balance sheet, but their approach the last time they did this may not be the best way this time around.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Officials “haven’t made any decisions at all about when runoff would start,” Powell told a press conference Wednesday after the Federal Open Market Committee sped up its removal of policy support to end asset purchases in mid-March.

Noting that policy makers had a first discussion on the balance sheet at their meeting and would keep the conversation going at their next meeting and the one after that, Powell said the debate included a focus on lesson’s learned.

“We looked back at what happened in the last cycle and people thought that was interesting and informative,” he said. “But to one degree or another people noted that this is just a different situation and those differences should inform the decisions we make about the balance sheet this time.”

Past experience shows that how the Fed manages its balance sheet matters, although the U.S. central bank has also adapted and in July 2021 it created two standing repo facilities to help ease money-market pressures at times of stress.

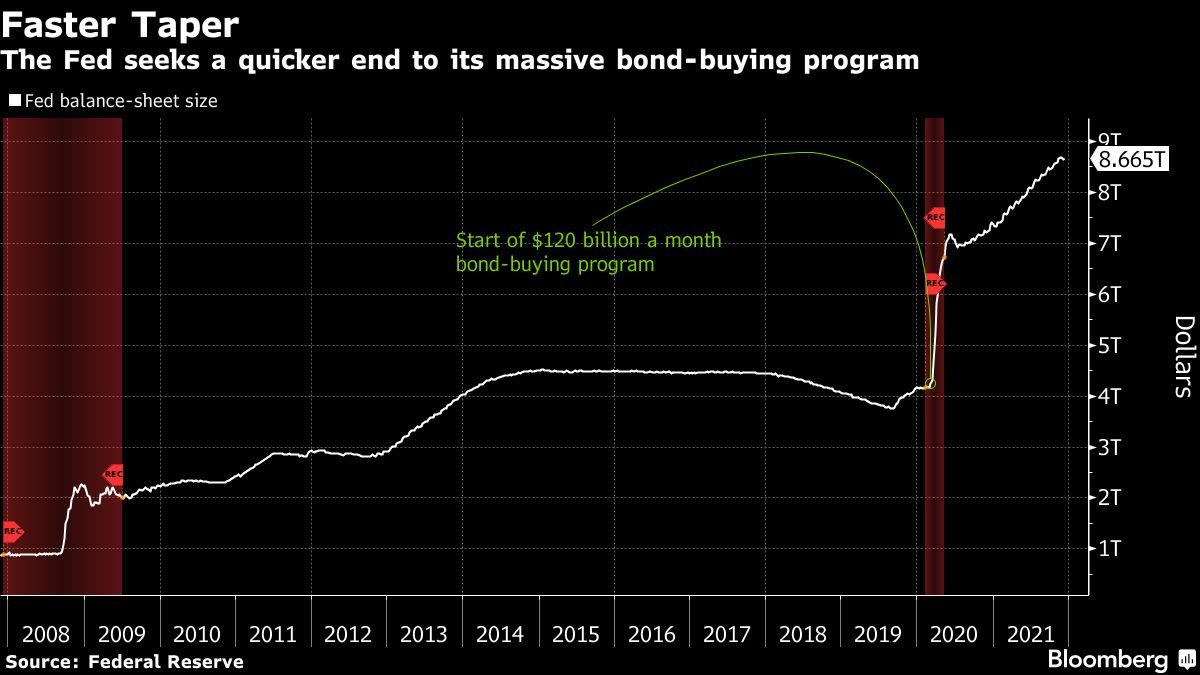

When the Fed wrapped up its last bond-buying campaign in October 2014 it continued to maintain the size of its balance sheet — which by then had ballooned to around $4.5 trillion — by reinvesting repayments of its Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities.

The central bank then started to cautiously raise its benchmark overnight policy rate in December 2015, after deciding that it preferred to use this as the primary tool for withdrawing policy support. The balance sheet’s size was maintained until October 2017, at which point the Fed began to gradually shrink it by allowing some of the holdings to roll off every month.

It did not sell any of the securities, which consisted of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. Selling assets might give rise to losses, which isn’t the case if the Fed holds an instrument to maturity. It doesn’t mark its holdings to market like a normal bank.

The unwind, which drains cash out of the banking system, continued for almost two years. The Fed continued to raise rates until severe stock and bond-market volatility forced a pause at the end of 2018. It then reversed course with three cuts in 2019.

In March of that year, it also announced a plan to slow the pace at which it was allowing the balance sheet to wind down, concluding the reduction in holdings at the end of September. From October it began to roll maturing MBS securities into Treasuries, capped at $20 billion a month.

‘Automatic Pilot’

While officials wanted the balance sheet to shrink on “automatic pilot” — as Powell said in December 2018 — dealers complained that money market liquidity was getting worryingly tight, which was causing harmful volatility.

Matters came to a head in the summer and fall of 2019 as turmoil in money markets raised questions about whether the Fed had gone too far in shrinking its securities holdings.

The New York Fed was forced to intervene with overnight cash loans in September. In October, with the balance sheet having shrunk to around $3.8 trillion, officials resumed asset purchases to restore the level of reserve in the banking system.

A few months later, as the Covid-19 pandemic began to spread, the Fed ramped up bond purchases aggressively to flood the banking system with cash and stem panic in financial markets. It exploded in size from $4.2 trillion in March 2020 to over $7 trillion by early June. It continues to grow and stood at nearly $8.7 trillion as of Wednesday.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.