Ambulances stationed outside the U.S. Capitol Building.

Adam Jeffery | CNBC

Nearly two years and six relief bills into the pandemic, the U.S. has spent the majority of its available Covid rescue funding. But billions of dollars across a handful of categories have not gone out the door.

Beginning under then-President Donald Trump and continuing through President Joe Biden’s administration, Congress has approved some $4.5 trillion in total aid spending, according to Treasury Department data. Federal agencies have formally committed to using about $4 trillion of that, and have made $3.5 trillion in actual payments to date.

It can often take time for the total pot of funds approved by lawmakers to make its way to the American people, budget experts say. That’s because government agencies such as the Small Business Administration and the Department of Labor go through a process of legally committing to a portion of allotted funding, which is known as obligating. They then start to actually spend it.

The $500 billion or so in available relief resources that have not been obligated may not end up being spent by agencies. There are deadlines for making these commitments, and they could span years. The details also vary by program. Funds that are not eventually obligated are returned for other government uses.

What agencies can commit to spending may differ from the initial estimates put forth in bills, or they may just plan to use the funds over a long-term period, said Kristen Kociolek, a director with the U.S. Government Accountability Office’s financial management and assurance team. A Congressional Budget Office estimate of outlays from March 2021’s nearly $2 trillion American Rescue Plan, for example, shows 40% of total spending is set to take place between 2022 and 2030.

Education, health care, and disaster relief are among the areas where the government has spent only a share of obligated funds, according to a CNBC analysis of Treasury data compiled by the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee, or PRAC. The agency was created as part of the March 2020 CARES Act to support oversight of pandemic relief spending.

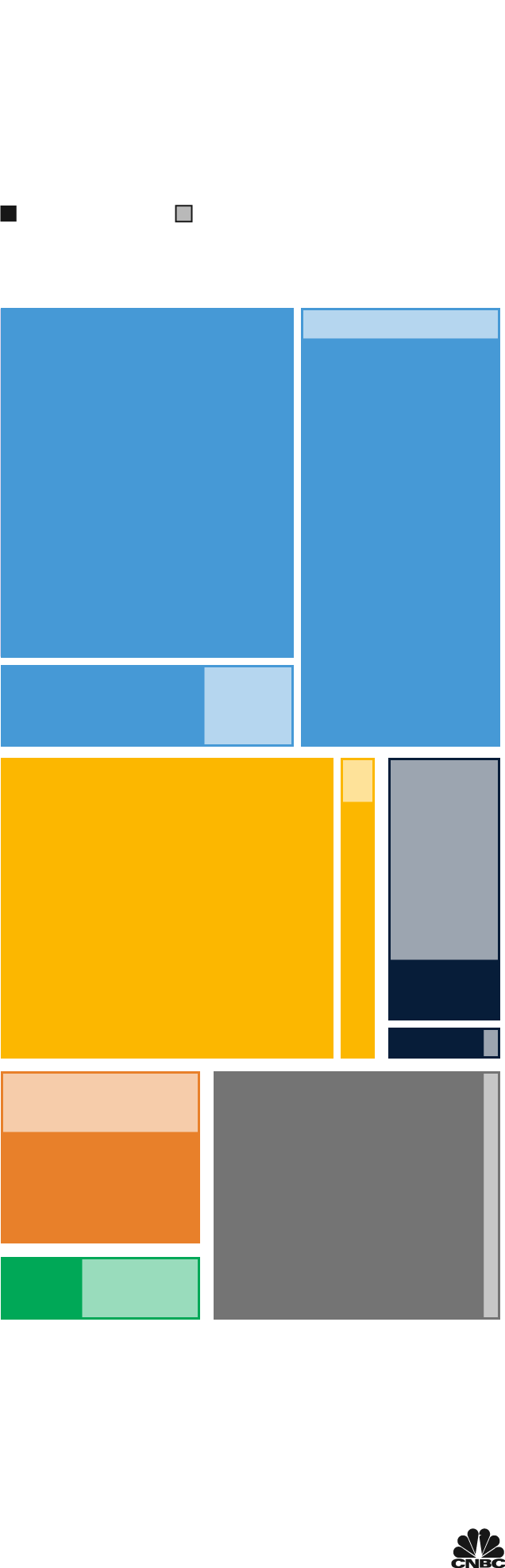

Covid relief funding, spent and remaining

Roughly $3.5 of $4 trillion in obligated, or committed, spending is out the door. Gaps

remain in education, health, and disaster relief.

Funds spent

Funds obligated but not spent

Labels show amount spent // amount remaining

Income security

Stimulus checks

$844B spent // $0 remaining

Unemployment

compensation

$666B // $56B

$192B // $111B

K-12, vocational

$60B // $203B

Other edu.

All other categories

$563B // $40B

Other income security

$145B // $67B

Paycheck Protection Program

$828B // $3B

Other commerce

Commerce and housing credit

Community and regional

development (includes

disaster relief) $48B // $75B

Note: Includes measures tied directly to spending. As of Dec. 6, 2021.

Source: CNBC analysis of Treasury data compiled by the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee

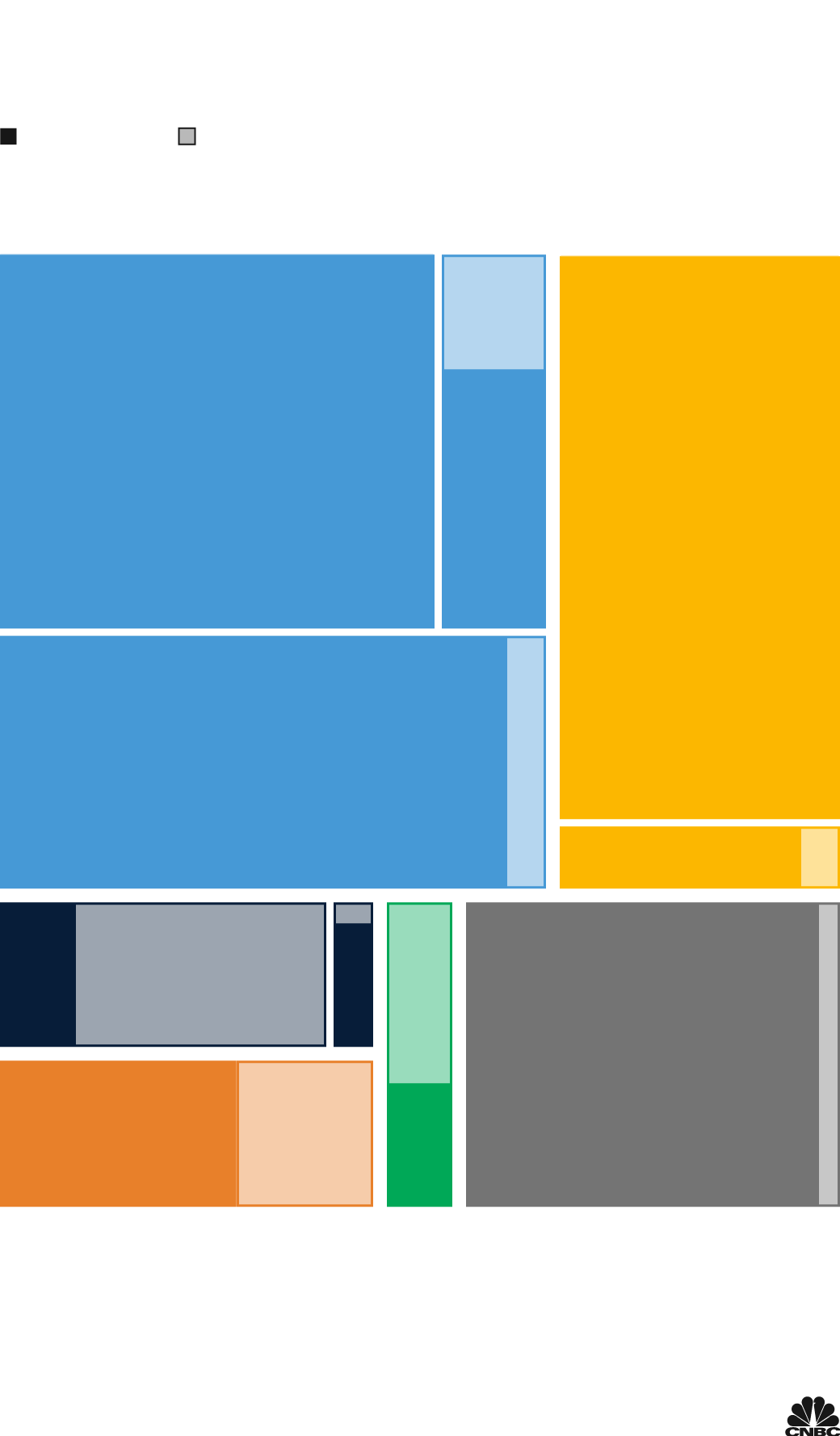

Covid relief funding, spent and

remaining

Roughly $3.5 of $4 trillion in obligated, or

committed, spending is out the door. Gaps

remain in education, health, and disaster relief.

Funds spent

Funds obligated but not spent

Labels show amount spent // amount remaining

Income security

Stimulus checks

$844B spent // $0 remaining

Unemployment

compensation

$666B // $56B

Other income

security

$145B // $67B

Commerce and housing credit

Paycheck Protection Program

$828B // $3B

K-12,

vocational

$60B //

$203B

Other commerce

All other categories

$563B // $40B

Health

$192B // $111B

Community and regional

development (includes

disaster relief) $48B // $75B

Note: Includes measures tied directly to spending.

Source: CNBC analysis of Treasury data compiled

by the Pandemic Response Accountability

Committee. As of Dec. 6, 2021.

Covid relief funding, spent and remaining

Roughly $3.5 of $4 trillion in obligated, or committed, spending is out the

door. Gaps remain in education, health, and disaster relief.

Funds spent

Funds obligated but not spent

Labels show amount spent // amount remaining

Commerce and

housing credit

Income security

Stimulus checks

$844B spent // $0 remaining

Paycheck Protection

Program

$828B // $3B

Other

income

security

$145B //

$67B

Unemployment compensation

$666B // $56B

Other commerce

All other categories

$563B // $40B

K-12, vocational

$60B // $203B

$192B // $111B

Community and regional

development (includes

disaster relief) $48B // $75B

Note: Includes measures tied directly to spending.

Source: CNBC analysis of Treasury data compiled by the Pandemic Response

Accountability Committee. As of Dec. 6, 2021.

The government plans to use nearly half of the remaining relief money in the future, said Marc Goldwein, a senior vice president with the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, or CRFB. A lack of demand may also have led to leftover money. Goldwein noted that a strong credit market might alleviate the need for Paycheck Protection Program loans.

Some programs also ended up costing less than initially expected. Half of U.S. states cut off enhanced unemployment benefits ahead of the Labor Day deadline, for example.

More money is available for education than any other category. Agencies obligated some $263 billion for elementary, secondary, and vocational education and nearly $60 billion has been spent to date, a difference of about $200 billion, the data show.

The more than $200 billion in total education funding remains on the table in part because schools have until 2025 to spend it. Congress set aside the cash largely to help restart in-person learning, but schools across the country have reopened their doors while using only a fraction of the funding.

The GAO noted in October that some states have used the money for programs to boost students who fell behind during virtual classes due to poor attendance or a lack of reliable internet access, among other factors.

Policymakers also have a significant share of health care services funding remaining, CNBC’s analysis found. The government has spent nearly two-thirds, or $192 billion, of the roughly $303 billion obligated, leaving $111 billion. The GAO noted that much of the money obligated for the Department of Health and Human Services is “available for a multiyear period or are available until expended.”

Agencies could use these funds as needed on efforts such as Covid-19 testing and treatment, according to Goldwein. Among potential uses for the money, the government could buy doses of the coming Pfizer antiviral Covid treatment, he said.

The government also has nearly $70 billion of the $114 billion obligated for disaster relief left to use, which may be deployed as needed going forward. The U.S. for the first time during the pandemic used the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s disaster relief fund — typically doled out in response to major natural disasters — to respond to a public health crisis.

In two of the most closely watched pandemic aid categories, the government has gone through nearly every obligated dollar. The U.S. has spent all of the roughly $844 billion set aside for direct payments to individuals, and has sent out all but $3 billion of the more than $830 billion obligated for Paycheck Protection Program small business loans.

The speed with which the virus wreaked havoc on the economy and the lack of information about how to contain it contributed to a uniquely large and fast government response.

“Compared to past recessions, what took years happened in weeks,” Goldwein said. “So the response was similarly fast.”

The unprecedented aid also was also driven by the conventional wisdom that Congress spent too little to fight the Great Recession over a decade ago, prompting lawmakers to “err on the side of caution” this time around, he added.

“Just one pandemic relief program — the $800 billion Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) — is equal to the federal government’s entire response to the 2008-2009 financial crisis,” wrote PRAC Chair Michael Horowitz in the group’s semiannual report to Congress published last week.

The initial bills were focused on getting money into Americans’ pockets as fast as possible to replace lost income as the U.S. unemployment rate spiked to nearly 15% in April 2020. The process became more refined over time, with additional restrictions added for PPP loans and supplemental unemployment benefits scaled down to an amount that would replace lost wages for the typical worker rather than pay them more than they earned while working.

The bulk of the allowed spending comes from the CARES Act and American Rescue Plan, bills passed in March of 2020 and 2021, respectively. Much of the money supported individuals and businesses, with more than $2 trillion coming in the form of stimulus checks, unemployment benefits, and Paycheck Protection Program loans, according to both PRAC and CRFB estimates.

Estimates from groups such as the PRAC and CRFB that attempt to capture a broader scope of the funding by including measures that are not directly tied to spending, such as tax credits, put the total Covid relief price tag at more than $5 trillion. The PRAC’s tracker shows a total of $5.2 trillion in allowed funding, while the CFRB’s tally is $5.7 trillion.

U.S. Covid cases and hospitalizations are on the rise and health officials are evaluating the threat of the newly-discovered omicron variant, which the World Health Organization on Wednesday said has the potential to change the course of the pandemic. The remaining relief dollars have some degree of flexibility — the government can use health spending for testing or vaccination efforts, for example — but any significant changes would likely require an act of Congress.

“You can’t take money that was supposed to go to testing and use it to send checks to people,” Goldwein said.