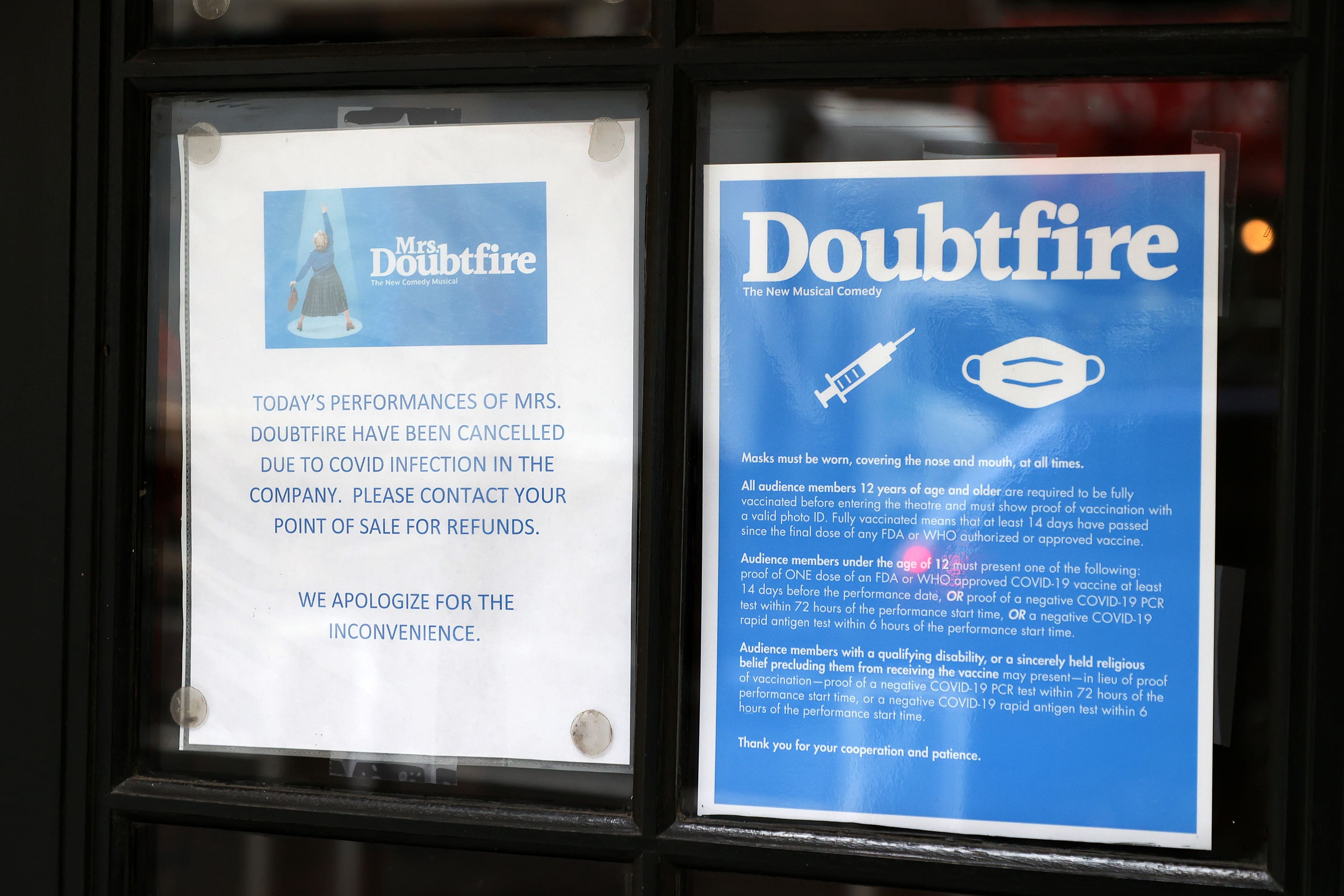

A sign indicating canceled performances of “Mrs. Doubtfire” due to Covid is displayed in the window of the Stephen Sondheim Theatre on December 16, 2021 in New York City.

Dia Dipasupil | Getty Images

After over a year of industry-wide closures, Broadway theaters finally reopened in September, but 2021 did not end the way theater professionals hoped it would. The late 2021 comeback had largely bucked London’s touch-and-go reopening earlier that summer: only a handful of Broadway productions temporarily closed due to delta infections. But omicron outbreaks late in the year stalled live theater. Before Christmas, 18 productions canceled performances. Five shows closed permanently in December, citing extreme uncertainty ahead this winter and increased challenges from the pandemic.

If some shows can’t go on under these conditions, how Broadway producers are choosing to close is creating a new labor controversy involving artists already among the hardest-hit by the pandemic.

Kevin McCollum, a prominent producer of numerous Broadway shows including the Tony Award-winning productions of “In the Heights,” “Avenue Q,” and “Rent” says he remains “very bullish on the theatre business,” but he just made a decision that has theater unions alarmed.

McCollum has multiple shows currently running on Broadway, including “Mrs. Doubtfire” and “Six,” but as omicron surged in New York City, “Mrs. Doubtfire” had yet to find its footing.

“Mrs. Doubtfire was especially vulnerable because [it] just opened,” McCollum said.

With no cast album (unlike the wildly popular show “Six”), he says opening the show as cases spiked was “like planting a sapling, but there’s a hurricane.”

Doubtfire was open for seven days before an omicron outbreak in the cast forced McCollum to cancel Sunday’s matinee performance on December 12. Due to infections, the show did not reopen until December 22. During the 11-show shutdown in December, McCollum says the production swung $3 million: $1.5 million in expenses and another $1.5 million in ticket sales refunded to customers. But the larger issue was the shutdown’s impact on advance ticket sales, coupled with negative to lukewarm reviews.

Prior to the shutdown, the show sold around $175,000 in ticket sales per day, a relatively decent figure compared to gross weekly ticket sales during the same period in 2019. After the shutdown, that number dropped to $50,000. “When a show cancels a performance due to Covid, we see an increased cancellation rate for all performances,” McCollum said.

The Broadway League suspended their publication of gross-ticket sales during the pandemic, making it impossible to verify box office performance. The Broadway League declined to comment.

The decrease in box office sales and increase in ticket cancellations was particularly concerning to McCollum as the holiday season is the most profitable, bolstering Broadway productions through the slower winter months. Family-oriented musicals, such as “Mrs. Doubtfire,” in particular benefit from the busy season.

“Especially for a family show, there are younger people who are not vaccinated, and with a family of four, none of them can come in because they’re not going to let their child wait outside,” McCollum said.

He remains optimistic that family-oriented productions will have a greater chance of survival later this spring, benefitting from rising vaccination rates among kids and FDA approval of booster shots for younger children.

But in the meantime, McCollum has made a move that has attracted controversy: the show must be suspended, with a plan to return, but no guarantee for any of the artists involved.

An unprecedented ‘Mrs. Doubtfire’ suspension

In a move described by unions as unprecedented for the Great White Way, McCollum decided to temporarily suspend performances until March 15. Soon after announcing the hiatus, two other productions followed in McCollum’s footsteps. “To Kill A Mockingbird,” the hit play based on Harper Lee’s novel of the same name, announced Wednesday that it would suspend performances until June (temporarily laying off the cast and crew), and reopen the show in a smaller theater. “Girl from the North Country,” a jukebox musical featuring the work of Bob Dylan, will also end its run this month, but the production is currently in “advanced talks” with the Shubert Organization to reopen at another Broadway theater later this spring.

McCollum says he’s “not just throwing in the towel.”

According to the producer, the cost of the shutdown will be between $750,000 and $1 million. However, if the show were to remain open and experience additional closures as infections permeate the cast and crew, the production would lose around half a million each week. Between a decrease in ticket sales, mounting last-minute ticket cancelations and refunds, the evaporation of group sales (which account for a large portion of box office sales), and a plethora of costs associated with Covid testing (which average $30,000 per week), McCollum says the show would be forced to close permanently if it attempted a January run.

Other producers have made the final curtain call. Among Broadway shows that have closed for good: “Thoughts of a Colored Man”, “Waitress”, “Jagged Little Pill”, “Diana”, and “Caroline or Change.”

The Temptations’ jukebox musical “Ain’t Too Proud” is closing later this month.

Theater unions push back

McCollum says the nine-week hiatus is the only viable option to keep the production open.

“I have to figure out a way to extend my operation,” he said. “Because with the 14 unions … we don’t have a mechanism to hibernate. We do have a mechanism to open and close. Therefore, using that binary mentality of opening and closing, I had to turn the show off … preserve my capital, and use it when the environment is more friendly towards a family show.”

But according to the NYC Musicians Union, who represents musicians on Broadway, there is a mechanism for a production to hibernate. Provisions in the union’s contract with Broadway productions allow producers to temporarily close for a maximum of eight weeks during the months of January, February, and September. To do so, producers must get permission from the union and open their books to prove the show is losing money. McCollum declined, forcing the production to officially shut down — albeit temporarily, if all goes according to plan.

The union claims the producers of “Mrs. Doubtfire” intentionally chose to close the production (rather than enter an official, union-sanctioned hiatus) to hide their finances. “Our Broadway contract does allow a show to go on hiatus in a way that protects everyone’s jobs and gives audiences the promise that the show will return. But some producers choose not to follow this route so they can hide their finances from us. Instead, they simply close down their shows completely, with a vague promise of re-opening,” Tino Gagliardi, the President of the NYC Musicians Union Local 802, said in a statement to CNBC.

A spokesperson for McCollum’s “Doubtfire” production said the producer’s decision to shut down rather than follow the procedure for a union-sanctioned hiatus was due to difficulties in coordinating a unified deal between multiple unions, who presented the producer with different terms.

NEW YORK, NEW YORK – DECEMBER 05: Producer Kevin McCollum poses at the opening night of the new musical based on the film “Mr. Doubtfire” on Broadway at The Stephen Sondheim Theatre on December 5, 2021 in New York City. (Photo by Bruce Glikas/Getty Images)

Bruce Glikas | Getty Images Entertainment | Getty Images

Actor’s Equity Association – the union that represents Broadway Actors – says their contract with the Broadway League includes language from the last century that permits a show to close for at least six weeks.

According to Mary McColl, the union’s executive director, the archaic provision was meant to prevent producers from closing a show, laying off the entire cast, and re-opening shortly after (often in a new city) to “revitalize” the production, potentially with a new cast. McColl, whose last day as executive director of AEA was Friday, told CNBC that “it was never contemplated that it was made to create a layoff circumstance, which is what it is being used for now.”

“Even though it might completely comport with that specific article in our contract, it was never contemplated that it would be used in this way. And I don’t believe that any producer, up until now, has actually put it out in the public realm as ‘this is just a hiatus,'” she said.

While omicron has put shows in a challenging financial position, she says producers like McCollum are using that as an excuse to engineer a new cost-cutting tool: producers suspend productions during the winter months when shows struggle to sell seats, a challenge facing the industry even before the pandemic.

“I think this producer really looks at this as a layoff that’s necessary in the winter,” McColl said. “I don’t think it’s just exclusive in their mind to the Covid situation we’re in, but to create a layoff provision in the production contract, which we do not have.”

She says the move to go on hiatus should have been bargained between the union and The Broadway League (which represents shows in negotiations with artist unions). The union attempted to negotiate, but The Broadway League refused. The League recently came under fire for its disparaging comments against understudies, in which president Charlotte St. Martin blamed show closures on “understudies that aren’t as efficient in delivering their role as the lead is.”

In declining to comment, The Broadway League added to CNBC that it “would refrain from commenting on an individual show’s business model.”

As a result of McCollum’s decision, 115 people will be laid off for at least nine weeks while the show is shuttered; an especially difficult prospect for theater artists who have been out of work for over a year. One of those workers losing her job is LaQuet Sharnell Pringle, who is a swing, understudy, and assistant dance captain for “Mrs. Doubtfire.” Pringle says she had to find additional streams of income while Broadway was closed for 18 months. Now, she is leaning on those side hustles again – entrepreneurial opportunities that include teaching, writing, and editing.

While McCollum argues the temporary closure will ensure “long-term employment,” others are not as optimistic about the show’s future.

“This is either going to be a wonderful idea that helps to keep live theater going during a global pandemic, or it is just prolonging us actually being closed,” Pringle said. “There’s the actor side of me that wants to believe in this [but there is also] the actor who has lived through this for going on two years now [that] says it might be too soon for theater to be back.”

Will the cast return?

It remains unclear whether the cast, crew, and musicians will return if the show re-opens in March, as many are still recovering from the significant financial blow of 18 months of unemployment and may look for work elsewhere.

Pringle is pondering another career, like many on Broadway, looking for work in less volatile sectors of the entertainment industry. “I’m auditioning for as much television and film as I can to get work that way,” she said. While she doesn’t think ongoing closures will dry up Broadway’s pool of talent, she says it will “severely injure it.”

She wants to continue with “Mrs. Doubtfire” but said, “I have to be smart, business-wise, and keep all my options open. … Actors care about the projects we’re attached to, but we also have to think about our livelihoods.”

“It’s been painful,” McCollum said. “There’s nothing harder than working in the theater.”

McCollum says Broadway’s need for mask-less employees coupled with a live performance poses a unique challenge to the theatre industry, in which Covid is more likely to spread and interfere with operations.

Another issue hitting many Broadway productions is the absence of older patrons, which theater heavily relies on. For the 2018-2019 season, the Broadway theatergoer was on average 42.3 years old. Conversely, film audiences skew younger. According to PostTrak’s Motion Picture Industry Survey, those aged 18-24 represent the largest demographic among moviegoers.

Despite the challenges, he insists that his team is “ready to do whatever we have to do to re-open the show in March” and he says those who want to return to the production can have their jobs back.

No guarantees

However, according to both unions, McCollum has not guaranteed that “Mrs. Doubtfire” will return in March, nor has he contractually guaranteed that the current musicians will remain with the show when it is scheduled to re-open. If he had closed the show temporarily under the union’s contractual provisions, he would be obligated to re-hire all musicians when the show resumes performances.

“Stopping a show abruptly and firing everyone creates a financial shock to our musicians and the other hardworking theater professionals,” Gagliardi said. “When a show closes like this, none of the artists have a guarantee of being re-hired when, or if, the show reopens. Artists deserve a written guarantee that they will be re-hired.”

The unions are collectively perplexed by McCollum’s resistance to working out a deal.

“If in fact, they’re saying we have to do this because we don’t have enough money to keep the show running, and we want to save enough money to reopen the show at a time when we think people will buy tickets, why would they not put that in writing so that the actors, and all the other workers, have some security, because everybody’s laid off,” McColl said.

Producers are also not obligated to re-hire the cast under the same terms of their original contract. In other words, the union will have to renegotiate the contracts when the show re-opens, and the actors could be paid less as a result.

The spokesman for the Doubtfire production said there are no guarantees to anyone who works on the show that it will re-open. “The show has closed. Kevin has said he will be offering everyone on the show their jobs back on March 15, if they want to come back,” the spokesman said. But he said anyone associated with the production has “no obligation to come back to the show if we don’t want to and we are free to take other employment if we wish.”

“When a show closes, their contract ends. Their contract is just negated regardless of how long it was supposed to run for,” outgoing AEA executive director McColl said, who added the union will be taking up issues related to the McCollum decision in its next negotiations, though she will no longer be leading it. “If they are an actor or stage manager who earns above the union minimum, which a lot of actors and stage managers do, they’re able to negotiate over scale. Without a guarantee that they’ll come back at that dollar amount, it’s possible that that producer would offer them less money to come back.”

McColl says that in negotiations with McCollum, the producer refused to put his words in writing. Although he has made a verbal “promise,” McColl says, “there is no guarantee that that’s going to happen,” and that is a difficult position for all of the workers, including actors, stage managers, musicians, stagehands and wardrobe workers on “Mrs. Doubtfire.”

To make matters worse, equity members’ health insurance is based on the number of weeks they work, and many workers will be unable to gain access to unemployment benefits, as some have not worked long enough since the 18-month shutdown to qualify.

Union officials are concerned that other shows, like “Mockingbird” and “Girl from North Country” have done, will enter similar hiatuses during slow months, dealing a significant blow to workers in the entertainment industry who will be without pay and health insurance while productions wait to open in a more fiscally advantageous environment.

The situations are different. Mockingbird is downsizing and moving to a new theater, while the Dylan musical is working on a new reopening plan. Unlike, Doubtfire, they were not in negotiations with unions that fell apart. Neither union commented on these shows to CNBC, but expressed concerns about the general trend of going on hiatus.

Producers for “Mockingbird” and “Girl from North Country” could not be immediately reached for comment.

“It’s just a terrible circumstance that our members find themselves in, and that the fact that is now being picked up by other shows is a really terrible situation,” McColl said. “If an employer wants something, usually the negotiation provides something in return for the worker. I see that coming for The Broadway League and their members. I see that coming.”

Missed this year’s CNBC’s At Work summit? Access the full sessions on demand at https://www.cnbcevents.com/worksummit/