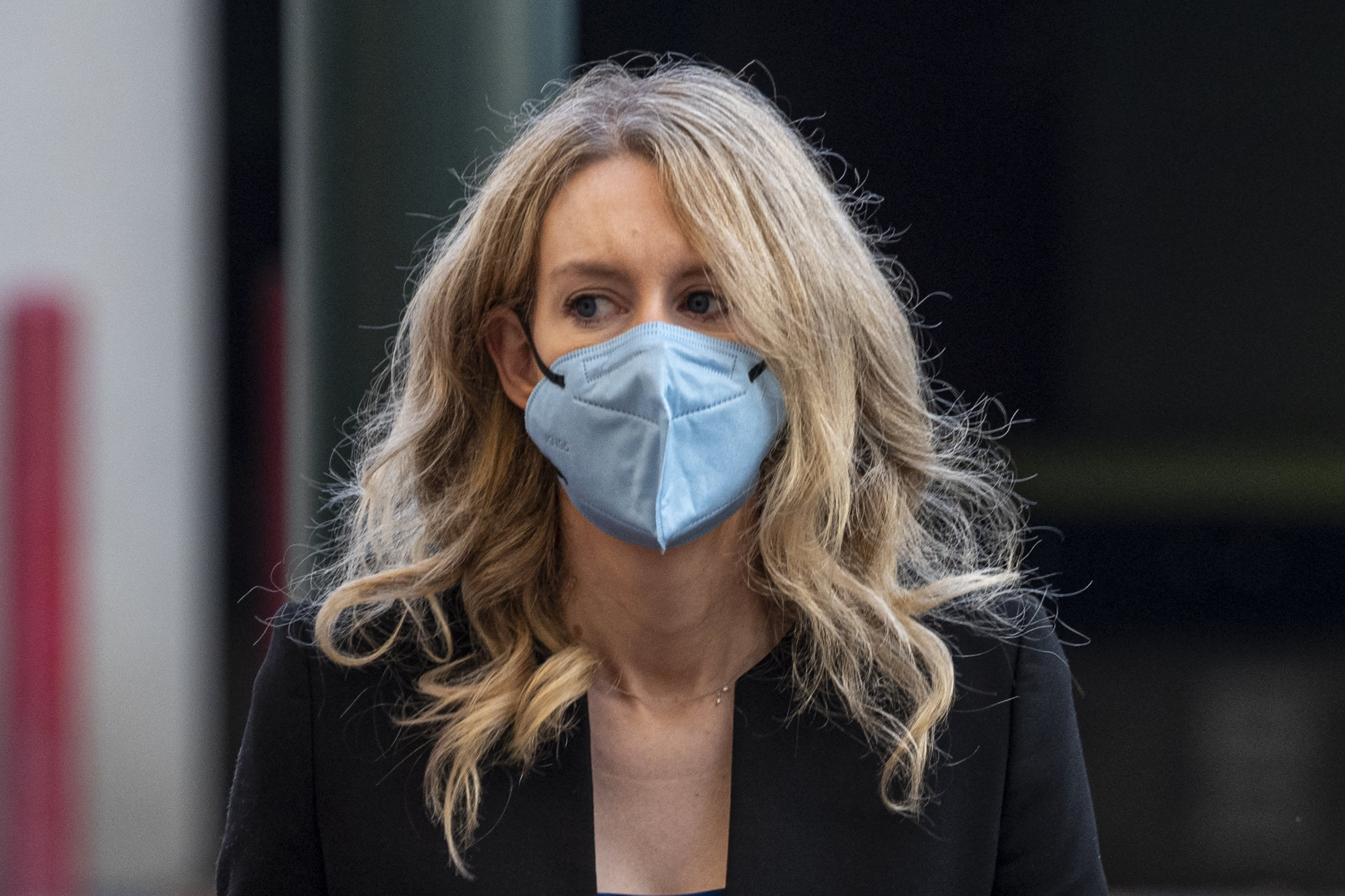

The case of Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes, convicted Monday on federal felony charges, has inspired books, podcasts, documentaries, and, coming soon, a feature film.

Now, get ready for a sequel of sorts: the criminal trial of former Theranos Chief Operating Officer Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani, Holmes’ mentor and ex-boyfriend, expected to begin in March.

A San Jose, Calif., jury convicted Holmes, 37, of conspiracy to defraud Theranos investors and three counts of wire fraud against three Theranos investors. But the panel acquitted her on conspiracy and fraud charges involving Theranos patients. The jury could not reach a unanimous verdict on three additional wire fraud charges against other Theranos investors, and U.S. District Judge Edward Davila declared a mistrial on those counts.

Balwani, 56, who worked alongside Holmes for nearly 7 years at Theranos after having befriended her when she was 18 and just out of high school, faces charges that are nearly identical to those in the Holmes case. He has pleaded not guilty.

University of Michigan Law Professor Barbara McQuade, a former United States Attorney and an NBC News legal analyst, said the mixed verdict in the Holmes trial means that both the prosecution and the defense in the Balwani case may need to recalibrate their strategies for the upcoming trial.

McQuade told CNBC’s “American Greed” that prosecutors will need to take a hard look at their case when it comes to Theranos patients.

“Knowing that this jury acquitted on all of the patient counts, I think that strategically, they should look to find a more direct way to explain why that is part of the fraud, that they necessarily knew that ultimately patients would be defrauded. And that although they didn’t know these individual patients by name, they knew that they existed in concept,” McQuade said.

She said prosecutors could even revise their indictment against Balwani, though that would almost certainly delay the trial. The government has not said whether it intends to change its strategy. Another hearing in the case is scheduled for Wednesday.

Balwani’s defense team could face far more pressing questions than the government does. After all, while the jury acquitted Holmes on some counts, it convicted her on four. The most serious crime, wire fraud, carries a maximum 20-year prison sentence.

“The jury did buy this whole theory,” McQuade said. “And, so, another jury might very well do the same.”

In fact, she said, it is not too late for Balwani to consider striking a plea bargain in exchange for a lighter sentence, though not as light as it might have been had he pleaded guilty ahead of Holmes’ trial and agreed to cooperate.

“Could we perhaps, enter a guilty plea and get a reduction for acceptance of responsibility?” she said. “It’s certainly something that you have to look at.”

An attorney for Balwani, Jeffrey Coopersmith, declined to comment for this story.

Under the bus

Balwani’s name came up frequently during Holmes’ trial, especially during her seven days on the witness stand. In emotional testimony, she claimed Balwani, nearly 20 years her senior, controlled all aspects of her life from her diet to her clothing to even her voice.

“He told me I didn’t know what I was doing in business, that my convictions were wrong, that he was astonished at my mediocrity,” Holmes testified. “And that I needed to kill the person I was to become what he called ‘a new Elizabeth’ that could be a successful entrepreneur.”

Holmes also claimed that Balwani forced himself on her sexually.

In a court filing ahead of the testimony, Coopersmith wrote that Balwani found the allegations “deeply offensive” and “devastating personally.”

Just as Holmes tried to throw Balwani under the bus in her trial, expect Balwani to return the favor, said McQuade.

“If you can point to the empty chair and say, ‘Oh, it’s all that other bad person,’ that other bad person isn’t there to defend themselves,” McQuade said. “She did it to Balwani in her trial, and I would expect Balwani to do it to Holmes in his trial.”

Balwani’s defense team has shown no indication so far that they might raise similarly intimate details of the couple’s relationship, but they may have plenty of other material to work with.

Text messages between the couple, introduced as evidence in the Holmes trial and likely to come up again in Balwani’s, show Balwani repeatedly alerting Holmes about issues at the company that she allegedly hid from investors, like a 2014 message in which he told her that a Theranos lab was “a f*cking disaster zone.”

Balwani’s defense team could try to use evidence like that to show that he acted in good faith, and that it was Holmes and others at Theranos who dropped the ball.

“One thing he could say is, ‘I didn’t have a background in science, I relied on only scientists to tell me whether the product work. My job was marketing and selling and accounting’,” McQuade said.

Holmes herself testified that she was the ultimate authority at Thernaos, acknowledging under cross-examination that she had the ability to fire Balwani at any time, but did not.

The two were supposed to go on trial together for their roles at Theranos, the blood-testing start-up that failed in 2018 following explosive revelations its supposedly revolutionary technology did not work as advertised. But after Holmes’ attorneys said they planned to level the abuse allegations, Judge Davila, who will also preside over Balwani’s trial, agreed to separate their cases.

“Such testimony would be unfairly prejudicial to codefendant Mr. Balwani such that he will be denied a fair trial unless his trial is severed from Ms. Holmes’s trial,” Davila wrote in a March 2020 order that was unsealed on the eve of Holmes’ trial in August.

A question of intent

While their cases may diverge on the question of who was responsible for problems at Theranos, there are also likely to be many common threads. Some pre-trial filings suggest that, like Holmes, Balwani may argue that he had no intent to commit fraud, a necessary element for the government to prove a crime.

In a pre-trial court filing on December 6, Balwani’s attorneys said they should be allowed to argue that he acted properly in his dealings with investors.

“Mr. Balwani should be permitted to argue that he viewed the amounts he collected from the alleged victims as genuine investments that he intended to make profitable,” the filing said.

Theranos, under Holmes and Balwani, raised some $945 million from investors, many of them prominent figures including Rupert Murdoch, the family of former Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos and the Walton family of Walmart fame.

Balwani’s defense team has also sought to limit evidence involving patients, including the results of tests that were performed using non-Theranos diagnostic equipment.

“Evidence going to the accuracy and reliability of patient tests is not relevant unless it goes to the accuracy and reliability of Theranos’ technology, not unmodified commercial technology,” they wrote in the Dec. 6 filing.

Prosecutors have argued that the use of third-party devices, which Theranos hid from the public, was part of the alleged fraud.

Whistleblower redux

As they did in the Holmes trial, former Theranos insiders are likely to testify that Balwani was an integral part of a secretive corporate culture that aggressively quashed dissent in order to hide problems from investors and patients.

Former Theranos lab associate-turned-whistleblower Erika Cheung, a prosecution witness in Holmes’ case who is also listed as a potential witness against Balwani, testified that when she began encountering inaccurate test results, she brought her concerns to Balwani.

“The feedback and reception I got from him was, ‘What makes you think you’re qualified to make these calls, you’re a recent grad out of UC Berkeley, what do you know about lab diagnostics?'” Cheung testified.

In an interview with “American Greed,” Cheung said that one of her first hints of trouble at Theranos was when she began emailing colleagues about the testing issues, and to her surprise, she heard back from Balwani.

“Sunny would respond to them out of nowhere. He wasn’t cc’d. He wasn’t bcc’d,” she said. “Things that we had said in certain context would be reiterated to us, like things we would say in private with one another.”

Cheung eventually took her concerns outside the company, sharing them with federal agents and with journalist John Carreyrou, who first exposed the issues at Theranos in the Wall Street Journal in 2015.

In a pre-trial motion filed on Nov. 19, Balwani’s attorneys sought to sharply limit Cheung’s testimony in the trial, arguing that having “worked at Theranos for a total of six months in an entry level position right out of college,” Cheung was unqualified to opine about alleged problems in the lab.

“These ‘observations’ require demonstrable expertise in the field of laboratory testing, but Ms. Cheung lacks any such expertise,” the filing said, alleging that when she testified in the Holmes trial, “she repeatedly opined on complex scientific matters and industry standards without any relevant expertise or knowledge.”

Assuming Cheung takes the stand again in Balwani’s trial, his attorneys will know almost exactly what to expect, thanks to her testimony in the Holmes case. McQuade said that poses some risks for the government.

“You always want to minimize the number of times a witness testified, just because most people, when they tell a story, will vary in the details just a little bit,” she said. “A skilled defense attorney can use that discrepancy skillfully in cross examination, to make the witness look like they’re either lying or sketchy on the details. And that can sometimes cause just enough doubt to cause a jury to acquit.”

McQuade said the ability to have seen the details of the government’s case in the Holmes trial — and knowing the verdict — provide advantages that Balwani would not have had if his trial had gone first as his attorneys initially requested.

But she cautioned both sides in the Balwani case not to read too much into the verdict in the Holmes trial.

“You never want to learn the lesson too well,” she said. “The mere fact that one jury found her guilty doesn’t mean another jury is going to find a different defendant guilty. I don’t think that they should assume that the next jury will automatically find the same way.”

See how Silicon Valley superstar Elizabeth Holmes’ grandiose promises to change the world came crashing to earth. Watch the ALL-NEW, 200th episode of “American Greed,” Wednesday, January 12 at 10pm ET on CNBC.