Here’s how the Federal Reserve may shrink its $8.77 trillion balance sheet to combat high inflation, according to a former Fed staffer

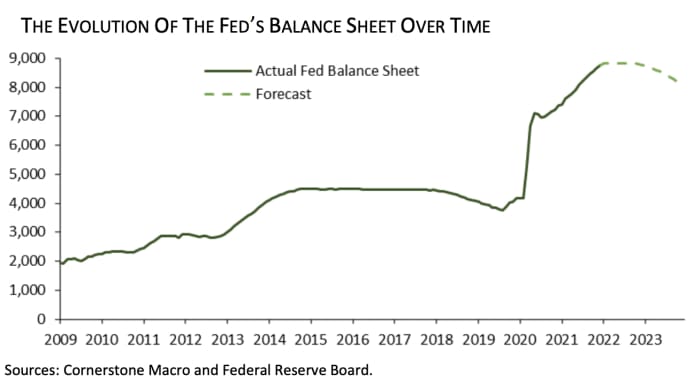

With the U.S. inflation rate at an almost 40-year high, Federal Reserve officials are likely to start shrinking their $8.77 trillion balance sheet earlier than they did the last time around from 2017 to 2019, and at a pace that may be twice as fast.

That’s according to Roberto Perli, a former senior Fed staffer in Washington, who envisions an initial reduction that starts at $20 billion per month for the first quarter, starting in June or September, and gradually rises to a $100 billion monthly pace by around the following year.

While policy makers haven’t yet decided when or how fast they’ll move this time around, Perli sees them following the basic blueprint of the previous episode, which involved using caps to establish an upper limit on the pace of reductions. However, he says, the Fed will also “be ready to slow, suspend, or stop the shrinking process at the first signs of market trouble.”

Eight straight months of annual headline consumer price readings at 5% or higher are putting pressure on the central bank to respond, with policy makers now preparing for a smaller balance sheet, alongside rate hikes in coming months. Analysts are currently trying to envision how such a dual tightening process might play out, just as Wednesday’s data showed consumer price gains pushing the headline year-over-year inflation rate to 7%, a nearly 40-year high.

“Nothing in the CPI report leads me to believe that the FOMC will be less inclined to move on the balance sheet along the lines I described,” Perli said by phone.

Wednesday’s CPI report gives further ammunition to policy makers such as Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester, who said she backs the process of shrinking the balance sheet “as fast as we can,” without pushing markets off track.

Minutes of the Fed’s Dec. 14-15 meeting, released Jan. 5, revealed that the policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee almost uniformly thought it would be appropriate to initiate balance-sheet runoff at some point after the first rate hike. In a question-and-answer following the central bank’s December policy update, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell hinted that the runoff would look different than when it was initiated in 2017, by saying “the economy is so much stronger now” and such differences should factor into policy makers’ thinking.

The Fed launched its current program of bond buying in March of 2020, to help stabilize the market for U.S. government debt at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic — a move that eventually led to a roughly doubling in the size of its asset portfolio in the past two years. Bond purchases, which keep long-term rates lower than they’d otherwise be, helps the economy by making it easier for consumers and businesses to borrow and spend.

In the eyes of some analysts, how the Fed handles its portfolio is perhaps more important than rate hikes, which may turn out to be meaningless in controlling inflation until the central bank tries to reduce its holdings.

Read: Forget Rate Hikes. How the Fed Handles Its $9 Trillion in Assets Is What Really Matters and Fed Weighs Proposals for Eventual Reduction in Bond Holdings

The timeline for shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet “will be much more compressed this time and the pace of shrinking should be faster given the better economic conditions and the larger size of the balance sheet,” Perli, a Washington-based partner and head of global policy for Cornerstone Macro, and others wrote in a report dated Tuesday.

In particular, they see a relatively “short delay” of one quarter or two between the time of the Fed’s initial rate hike and the start of balance-sheet shrinking, versus the seven quarters it took last time around. With the CME FedWatch Tool reflecting a 74% chance of a 25 basis point hike in March, which would take the fed funds rate target to 0.25%-0.5%, that would put the commencement of quantitative tightening in June or September.

Cornerstone Macro also expects that the pace of shrinking will be about double that of 2017-19, considering that the balance sheet is about twice as large as back then, and will occur through what Perli describes as “attrition only” or no asset sales. Assuming that the shrinking process is split between Treasurys and mortgage-backed securities, Cornerstone Macro estimates that the Fed will be able to eliminate $531 billion of Treasuries over the first five quarters of quantitative tightening. The amount of runoff in MBS will depend on prepayments, which could be slow because higher interest rates make mortgage refinancing less attractive.

During the Fed’s 2017-19 round of tapering, policy makers were attempting to shrink the central bank’s balance sheet back to a more normal size nearly a decade after the end of the 2008 financial crisis, and not out of any concerns about inflation.

On Wednesday, Treasury yields traded mixed after the CPI report. Meanwhile, the spread between 2- TMUBMUSD02Y,

Sign up for our Market Watch Newsletters here