Roaring U.S. housing market may cool, keep climbing as Fed ends emergency support

U.S. home prices roared almost 20% higher in the past year, giving families who own properties a major boost to their finances during the pandemic.

But Wall Street, a key source of home mortgage finance, sees important questions ahead for the red-hot housing market, now that the Federal Reserve has shifted its focus to tackle inflation as the economy recovers from the pandemic.

“House price appreciation was a significant contributor to growing household net

worth and will likely slow due to higher interest rates and declining affordability,” Brad Tank and Neuberger Berman’s fixed-income investment strategy team, wrote in their first-quarter outlook.

“Additionally, federal forbearance programs for mortgages have not been renewed and households benefitting from relief will be required to resume payment.”

The Fed’s December policy pivot includes a plan to raise benchmark interest rates at a quicker pace than expected only weeks before, but also a faster end to its emergency bond-buying program, now likely by March.

That leaves the market with “two main questions,” according to the Neuberger team, namely, how much mortgage bond supply others will need to absorb as the Fed shrinks its near $8.8 trillion balance sheet. Also, what happens to home price appreciation and refinancing activity if interest rates rise as much as expected?

Read: Housing is in the grip of an inflation storm — and it’s exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic

Why housing’s not like 2008

After the 2008 financial crisis, the government’s prominence in the U.S. housing market grew, in part though its mortgage guarantees, but also its amassing of bonds in the $8.2 trillion agency mortgage market.

Agency mortgage bonds accounted for 66% of all housing debt in December, according to the Urban Institute. That made the sector a benchmark for 30-year mortgage rates, including during the recent refinancing boom as lenders originated more than $1 trillion in home loans a quarter.

The government’s outsize footprint in the mortgage market has meant sway over mortgage rates and lending standards after the subprime debacle a decade ago, but it also directed federal housing relief during the pandemic to prevent a wave of evictions and foreclosures.

Many borrowers reeling from job losses in 2020 stayed in their homes, instead of facing late fees, collections and worse, until the economy could return to a more solid footing.

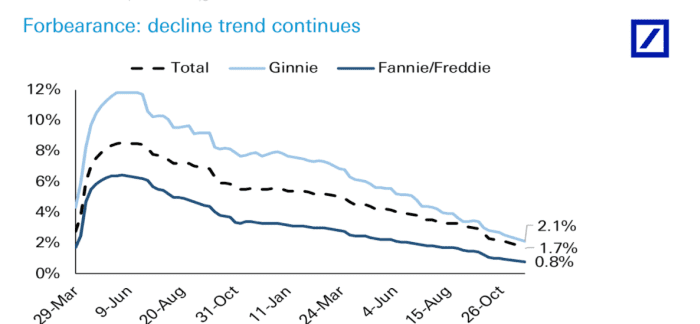

Now, forbearance rates on all home mortgages, even those held by banks, have sharply declined from their pandemic peak, recently pegged at a low 1.7% in November (see chart), on the back of higher wages and low unemployment.

Plunging home loan delinquencies

Deutsche Bank

In terms of households, that means only about 835,000 homeowners in November were in forbearance, whereas 4 million before the pandemic, according to Deutsche Bank researchers.

Other major departures from last decade’s crisis include a current housing shortage, rather than an oversupply, coupled with an new era of institutional landlords in the single-family rental market.

That’s meant deep-pocketed private-equity owners, Zillow Z,

Mortgage experts say the dynamic could help home prices continue to rise at a more normalized rate in 2022, even if 30-year mortgage rates rise and properties become harder for families to afford.

“Rising rates don’t cause home prices to go negative, but they certainly can slow down the growth in home price appreciation,” said Scott Buchta, head of fixed-income strategy at Brean Capital, in a phone call.

His forecast is for prices to rise 6% to 10% this year, depending in part on where 30-year mortgage rates shake out.

What rate is too high?

As in the wake of the 2008 crisis, the Fed in the past two years has loaded up its balance sheet with Treasurys and agency mortgage-backed securities during the pandemic, in a bid to keep liquidity flowing and credit affordable.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell now hopes to engineer a “soft landing,” by raising interest rates and tightening financial conditions to rein in inflation, without hurting the job market or sparking a recession.

Many on Wall Street now expect short-term rates, potentially, to increase four times this year from the current 0% to 0.25% range. Longer-term rates, however, likely will hinge on how aggressively the central bank shrinks its mortgage bond holdings, Buchta said, particularly as the Fed works to get annual inflation closer to its 2% target from 7% as of December.

“I don’t think they want to shock markets,” he said, noting that home price appreciation historically has run about 2% to 3% above inflation, or roughly 5% growth yearly. “20% is not sustainable.”

That said, every 100 basis-point increase in the 30-year mortgage rate translates to about a 13% decline in purchasing power for a homeowner relying on financing, according to Buchta’s estimates.

In other words, the affordability that’s already a problem for many families priced out of the market could get much worse.

Also see: Interest rates are rising — but the Fed’s actions could make it easier to get a mortgage