Traders Wanted in a Once-Sleepy Gas Market With New Kingpins

(Bloomberg) — Around the world, analysts and traders are grappling with the biggest shakeup in the 60-year history of liquefied natural gas: The emergence of two new superpowers, the U.S. and China, who are bringing more uncertainty and price fluctuations to a once-staid commodity market.

Most Read from Bloomberg

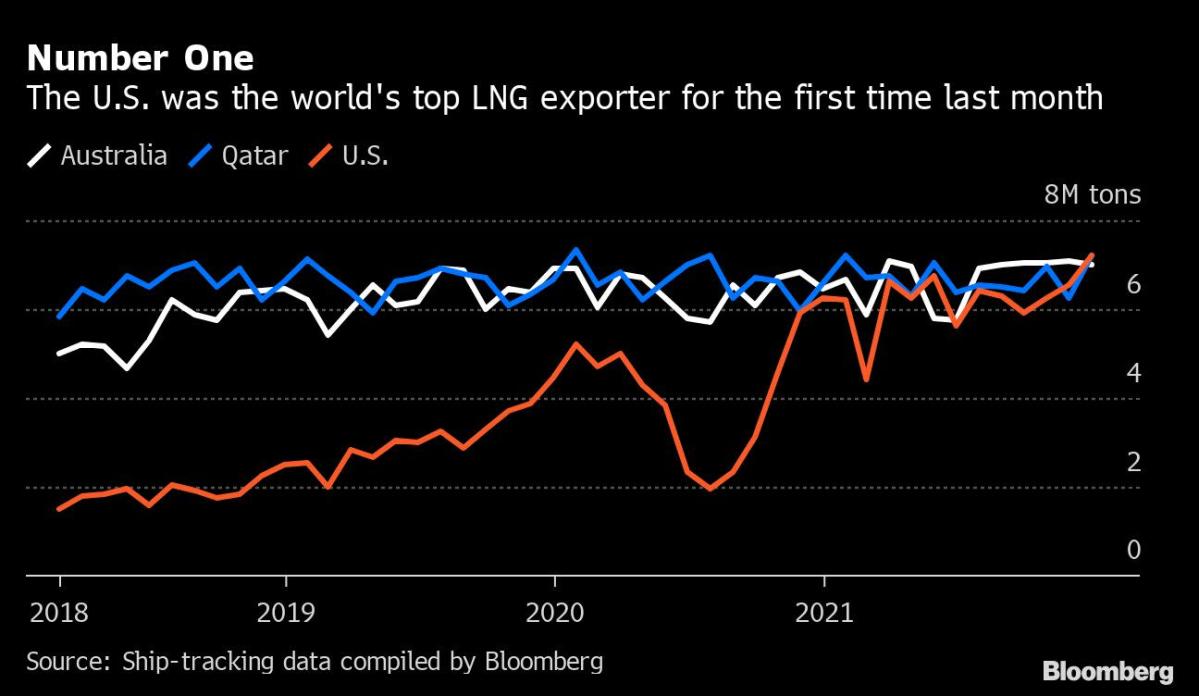

China became the biggest importer of liquefied natural gas in December, overtaking Japan for the first time since it pioneered the industry in the 1970s. Meanwhile, the U.S. is set to become the world’s top exporter of the fossil fuel on an annual basis later this year, beating out cornerstone suppliers Qatar and Australia.

Neither of the two superpowers are as predictable as their predecessors, and data from China is particularly hard to come by. As a result, LNG prices have seen wild swings as it’s become a traded commodity, similar to crude oil. To keep up, trading desks have proliferated globally, with Japanese LNG giants like Jera Corp. and Tokyo Gas Co. set up their own, while banks like Macquarie Group and Citigroup Inc. are hiring traders to cash in on the volatility.

Gas markets have never been this volatile. They’re trading up and down on single days in ranges they barely covered over decades. European natural gas prices, often used as a benchmark for LNG, hit a record high of 180 euros per megawatt-hour in mid-December, before collapsing more than 60% in the next 10 days.

The changes have given China enormous weight within the market because it can more easily influence spot rates or long-term pricing norms.

In Moscow, Ronald Smith, a senior analyst at broker BCS Global Markets, which provides research to investors in LNG derivatives, says his clients sometimes spend hours hunting for minutiae out of China, like the number of trucks shifting from diesel to natural gas. But such data, which can help predict Chinese demand, can be hard to come by, he said.

“Gas prices could give big surprises when China demand grows stronger or weaker than the market thought,” said Smith. “Predicting U.S. supply is easier,” he said, though there are sometimes unexpected developments there too, like cargoes meant for Asia suddenly heading to Europe.

For much of its history, LNG — natural gas in liquid form that’s used for everything from transportation to heating — was only bought and sold via rigid multi-decade contracts. That method simply involved ferrying the fuel between two nations, using legacy pricing mechanisms linked to crude oil.

Changes came after hydraulic fracturing unlocked vast U.S. shale gas reserves starting just over a decade ago, transforming the country from a net importer of the fuel to an exporter. The U.S. is now expected to have the world’s largest export capacity by the end of 2022, once a new terminal comes online in Louisiana.

U.S. LNG contracts are among the most flexible in the industry, allowing buyers to take their gas wherever it’s most needed — or to whoever will pay the most. Buyers can even pay a fee to cancel the shipment altogether when it isn’t economical, as was the case in 2020 when spot prices crashed to record low levels. This is perfect for nimble traders seeking to make profits off price arbitrage between regions.

American LNG producers also broke the industry-wide norm of pricing shipments to crude oil, opting instead to sell cargoes linked to the domestic Henry Hub gas marker, the main pricing point for U.S. futures contracts for the fuel and the name of the delivery location in Louisiana where several pipelines intersect.

Robust shale output has helped keep U.S. gas prices lower than overseas rivals.

The U.S. has, meanwhile, gained greater heft within the market. Just in the last month, a surge in American LNG deliveries to Europe helped cool off a record-breaking spot price rally as Russian supplies remained weak.

Still, the greater flexibility brought in by the U.S. comes with a raft of new challenges. Traders must now closely monitor hurricane disruptions in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico, while political action — like stricter emissions guidelines — could boost the price of LNG shipments.

There are also other risks since the U.S. and China are ascending at the same time. Just a few years ago, LNG was swept up into a tit-for-tat trade war between Beijing and Washington. Chinese firms temporarily stopped importing U.S. LNG cargoes or signing longer-term supply contracts after Beijing slapped tariffs on shipments in retaliation for American levies in 2018.

The emergence of U.S. and China is “a big shake-up, especially given their geopolitical rivalry,” Nikos Tsafos, James R. Schlesinger Chair in Energy and Geopolitics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. There is the “possibility that their tensions could disrupt markets.”

China started up its first LNG terminal in 2006, and its import volume was a measly 20 million tons in 2015 — just a fourth of Japan’s total deliveries. That quickly changed as China accelerated an effort to replace coal with gas to heat houses and fuel industries in a bid to curb emissions.

China’s historic demand — now at about 80 million tons a year — presents an outsized business opportunity for legacy suppliers and a batch of new hopefuls. Still, China is something of an unknown for the industry, especially as many smaller, so-called second-tier LNG importers begin to flood the market seeking to sign deals and buy spot shipments.

Shipments may have to quickly change directions on a dime if China’s government suddenly decides it needs spot shipments to feed its economy or if a geopolitical flareup results in sanctions.

China is “one country whose decisions can move the spot LNG market,” said Tsafos.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.