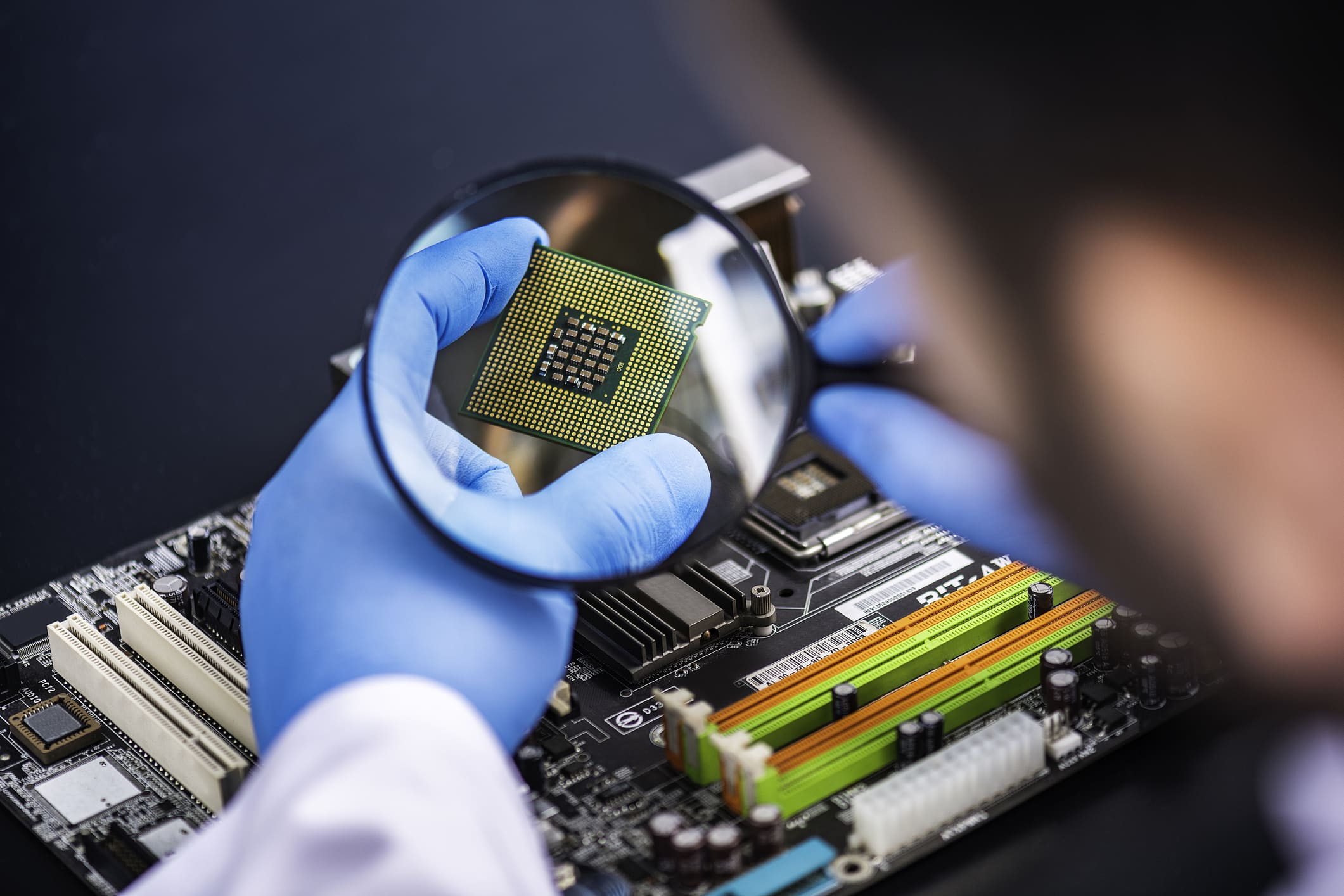

A technologist inspects a computer chip.

Sefa Ozel | E+ | Getty Images

European Union lawmakers have laid out ambitious plans to significantly ramp up production of semiconductors in the bloc and become a global leader in the industry.

To do that, it will need some of the key players from Asia and the U.S. to invest heavily in the continent, given the EU’s lack of technology in critical areas like manufacturing, analysts said.

On Tuesday, the European Commission, the executive arm of the EU, launched the European Chips Act — a multi-billion euro attempt to secure its supply chains, avert shortages of semiconductors in the future, and promote investment into the industry. It still requires approval from EU lawmakers to pass.

Chips are critical for products from refrigerators to cars and smartphones, but a global crunch has impacted industries across the board causing production standstills and shortages of products.

Semiconductors have become a national security issue for the U.S., and has even become a point of geopolitical tension between the U.S. and China. That clash over semiconductors has led to sanctions on China’s biggest chipmaker SMIC and the world’s second-largest economy doubling down on efforts to boost self-sufficiency.

The EU is now trying to mitigate some of those risks with its latest proposal.

“Faced with growing geopolitical tensions, fast growth in demand, and the possibility of further disruptions in the supply chain, Europe must use its strengths and put in place effective mechanisms to establish greater leadership positions and ensure security of supply within the global industrial chain,” the European Commission said.

Manufacturing challenge

The EU Chips Act looks to plough 43 billion euros ($49 billion) of investment into the semiconductor industry and help the bloc to become an “industrial leader” in the future.

Specifically, the EU wants to boost its market share of chip production to 20% by 2030, from 9% currently, and produce the “most sophisticated and energy-efficient semiconductors in Europe.”

Part of its plan involves reducing “excessive dependencies,” though the EU notes the need for partnerships with “like-minded partners.”

As it looks to become more self-sufficient, the EU will still rely heavily on the U.S. and in particular, Asia. That’s because of the quirks of the semiconductor supply chain and the changing nature of the industry.

Over the last 15 years or so, companies have begun shifting to a fabless model — where they design chips but outsource the manufacturing to a foundry.

In the actual manufacturing of chips, Asian companies now dominate, led by Taiwan’s TSMC which has about a 50% market share in terms of foundry revenue. South Korea’s Samsung is the next biggest, followed by Taiwan’s UMC.

U.S. firm Intel, which was once a key player, has fallen behind in recent years. However, it is now focusing on the foundry business and plans to make chips for other players. But its technology still remains behind the likes of TSMC and Samsung which can make the most cutting-edge chips that go into the latest smartphones, for example. Intel said last year it plans to spend $20 billion on two new chip plants in Arizona, in a bid to catch up.

The EU, however, has no companies that can manufacture the latest chips.

“The primary area the EU will need to partner is in bleeding edge wafer manufacturing. EU players today are stuck at 22nm and it’s unrealistic to think that local EU players can catch up from 22nm (nanometers) to 2nm,” Peter Hanbury, a semiconductor analyst at research firm Bain, told CNBC.

The nanometer number indicates the size of the transistors on the chip. A small number means a higher number of transistors can fit, leading to potentially more powerful chips. The chip in Apple’s latest iPhone, for example, is 5nm. These are considered the leading-edge chips.

EU companies may also rely on semiconductor design tools from the U.S.

Boosting chip production to 20% market share is an “an extremely tall order” for the EU, according to Geoff Blaber, CEO of CCS Insights. “The focus on manufacturing is the biggest challenge there,” Blaber told CNBC.

Is the EU attractive enough?

As countries and regions around the world look to secure their semiconductor supplies, there is growing competition to secure talent and convince companies to invest.

As part of a $2 trillion economic stimulus package, U.S. President Joe Biden earmarked $50 billion for semiconductor manufacturing and research. A bill known as the CHIPS for America Act is also working its way through the legislative process.

Countries like Japan, South Korea and China are all boosting investment into semiconductors too.

“The primary challenge will be in attracting new players to the EU. Specifically, the EU must become a more attractive location than other geographies,” Hanbury said.

The EU has been trying to woo leading-edge chip manufacturers. Intel is planning to build a new chip fab in Europe, although a specific site has not yet been chosen. TSMC is in the early stages of assessing its own production facility in Europe.

“The EU (or any geography) doesn’t need to outspend the semiconductor players but rather to influence their spend to occur in their geography,” Hanbury said.

EU strengths

Even though European firms are behind in the latest manufacturing technology, the EU still has some key players in the semiconductor industry.

One of the most important is ASML, a Dutch firm that makes a machine used by the likes of TSMC, and is used to make the most cutting-edge chips. Apple suppliers STMicro and NXP are also both based in Europe.

“[The] EU has several key assets in the industry,” Hanbury said.

The EU’s focus could be on securing chip supply for sectors where European firms have a large presence such as the automotive industry. Semiconductors that go into cars are often less advanced and don’t require the latest manufacturing technology.

“Think about some of those sectors where we’re going to see the demand for the technology in the coming years and automotive is one big opportunity in Europe and I think that’s something I’d expect the EU to be focusing on,” Blaber said.