‘This is not 1980’: What investors are watching as next U.S. inflation reading looms

Investors next week will be closely watching for the latest reading on U.S. inflation, which has been running hot against the backdrop of a volatile stock market in 2022.

“Inflation will be the data point that moves markets next week,” said Brent Schutte, chief investment strategist at Northwestern Mutual Wealth Management Co., in a phone interview. “I think what you’re going to continue to see is a rotation towards those cheaper segments of the market.”

Investors have been jittery over their expectations for the Federal Reserve to take hawkish monetary policy steps toward combating inflation by raising interest rates from near zero. Rate-sensitive, high-growth stocks have been particularly hard hit so far this year, and some investors worry the Fed will hurt the economy if it hikes rates too much too fast.

“The Fed’s goal is not a recession,” said Schutte, who expects monetary tightening will be more of a “fine-tuning” under Chair Jerome Powell. “This is not 1980.”

Paul Volcker, who became Fed Chair in August 1979, helped tame soaring inflation by aggressively raising the Fed’s benchmark interest rates in the 1980s, DataTrek Research co-founder Nicholas Colas said in a Feb. 3 note. “Fed Funds ran far higher than CPI inflation for his entire tenure.”

“Especially notable is the wide gap in 1981 – 1982, when he kept rates very high (10 – 19 percent) even as inflation was clearly in decline,” Colas wrote. “This policy caused a recession,” he said, “but it also had the effect of quickly reducing inflationary pressures.”

The consumer-price index, or CPI, showed inflation rose 0.5% in December, bringing the annual rate to a 40-year high of 7%. The CPI reading for January is slated for release on Thursday morning.

“The longer high inflation persists, the more unnerving it will be for market participants,” said Mark Luschini, chief investment strategist at Janney Montgomery Scott, by phone.

Inflation loitering hotter for longer may “engender a much more aggressive Federal Reserve response and as a consequence could undermine the lofty valuations for the market at large,” said Luschini, “particularly those long-duration growth sectors like technology that have already suffered over the past month.”

Shelter, energy and wages are among the areas drawing the attention of investors and analysts as they monitor the rising cost of living during the pandemic, according to market strategists.

Barclays analysts expect that “inflationary pressures moderated slightly in January, primarily in the core goods category,” according to their Feb. 3 research note. They forecast headline CPI rose 0.40% last month and climbed 7.2% over the past year.

As for core CPI, which strips out food and energy, the analysts expect prices rose 0.46% in January for a 12-month pace of 5.9%, “led by continued firmness in core goods inflation, and strength in shelter CPI.”

Meanwhile, rising energy prices are part of the inflation framework that “we are watching along with everyone else,” said Whitney Sweeney, investment strategist at Schroders, in a phone interview. Elevated oil prices are worrying as Americans wind up feeling the pinch at the gas pump, leaving people with less disposable income to spend in the economy, said Sweeney.

West Texas Intermediate Crude for March delivery CLH22,

Read: U.S. oil benchmark posts highest finish since September 2014

“Commodity prices more broadly are showing no signs of abating and are instead continuing to trend higher,” Deutsche Bank analysts said in a research note dated Feb. 2. “It’ll be much more difficult to get the inflation numbers to move lower if a number of important commodities continue to show sizeable year-on-year gains.”

Digging into the role of energy during 1970s inflation, DataTrek’s Colas wrote in his note that former Fed Chair Volcker did not “single-handedly tame inflation and price volatility in the early 1980s with rate policy.” He had some help from two areas, including a steep drop in oil prices and changes to the calculation of shelter inflation, said Colas.

Crude prices jumped from $1-$2 a barrel in 1970 to $40 in 1980, but then saw a 75% drop from 1980 to 1986, the DataTrek note shows. After peaking in November 1980, oil went “pretty much straight to $10/barrel in 1986,” Colas wrote. “Gasoline prices followed the same trend.”

Volcker also had some help taming inflation from the Bureau of Labor Statistics changing its calculation of shelter inflation to remove the effect of interest rates, according to DataTrek. Shelter costs, like rent, represent a significant portion of CPI and it’s an area of inflation that tends to be “stickier,” which is why investors are watching it closely as they try to gauge how aggressive the Fed may need to be in fighting the rise in cost of living, said Sweeney.

“Monetary policy is important, but so are factors outside the Fed’s control,” Colas wrote in his note. “Perhaps supply chain issues will fade this year the way oil prices did in the 1980s. If not, then the Fed will face some hard choices.”

Market strategists including Sweeney, Northwestern Mutual’s Schutte, Janney’s Luschini and Liz Ann Sonders of Charles Schwab told MarketWatch that they expect inflation may begin to subside later this year as supply-chain bottlenecks ease and consumers increase their spending on services as the pandemic recedes rather than goods.

The surge in inflation since the lockdowns of the pandemic has been goods-related, Sonders, chief investment strategist at Charles Schwab, said by phone. Elevated demand from consumers will subside as COVID-19 loosens its grip on the economy, she said, potentially leaving companies with a glut of goods, in contrast to shortages that have helped fuel inflation.

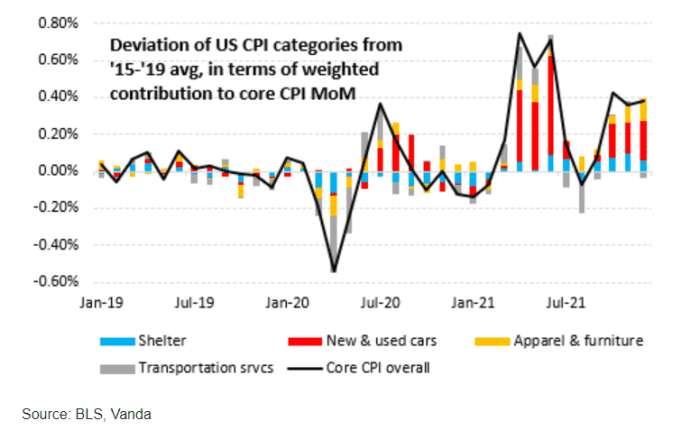

Meanwhile, “core CPI upside continues to be driven primarily by rising auto and, to a far lesser extent, apparel and furniture prices,” according to Eric Liu, head of research at Vanda.

“Transportation services costs – mainly in the form of volatile airfares – remain a source” of month-over-month variability, he wrote in an emailed note published around the end of January. “And shelter price growth continues to creep higher, albeit at a far slower pace than inflation in cars, furniture, etc.”

Liu estimates the CPI print next week could come in below consensus expectations, according to his note. That’s partly because used car prices appear to have peaked around mid-January, he said, citing data from CarGurus. Declining transportation costs, such as airfare and rental-car rates, also could shave off basis points from core CPI in January, he said, citing U.S. data from airfares analytics site Hopper.

Looking more broadly at inflation, Charles Schwab’s Sonders said she’s paying close attention to wage growth as it also tends to be “stickier.”

As wages go up, so do labor costs for companies. “They then pass on those higher costs to the end customer” in order to protect their profit margins, she said. Seeing their cost of living rising, workers then ask for higher wages to offset that, potentially creating a “spiral” of inflation.

A strong U.S. jobs report Friday showed average hourly wages rose 0.7% to $31.63 in January. Over the past year wages have jumped 5.7%, the biggest increase in decades.

See: U.S. gains 467,000 jobs in January and hiring was much stronger at end of 2021 despite omicron

Major U.S. stock indexes mostly rose Friday amid choppy trade as investors weighed the unexpectedly strong January jobs report against their expectations for rate hikes by the Fed. The S&P 500 SPX,