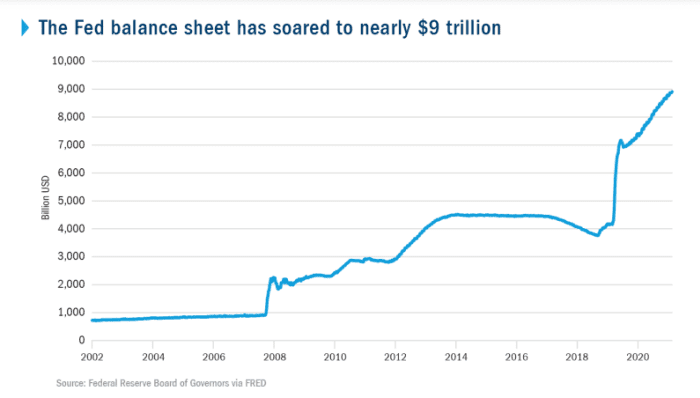

How the Federal Reserve could cut its near $9 trillion balance sheet as it fights inflation

Slimming down might be the trickiest part after two years of the pandemic.

As the Federal Reserve looks to shrink its near $9 trillion balance sheet to help cool U.S. inflation pegged at a 40-year high, the process might not be as straightforward as its two-year growth streak, according to Edward Al-Hussainy, a senior interest rates strategist at Columbia Threadneedle Investments.

“At the height of the pandemic, the Fed pumped billions of dollars into the financial system through asset purchases to support markets and the broader economy,” Al-Hussainy, wrote in a Tuesday client note.

Its monthly bond-buying program of Treasurys TMUBMUSD10Y,

Federal Reserve balance sheet soars to almost $9 trillion

Columbia Threadneedle Investments

Now likely comes the harder part.

Fed Chair Powell has shifted focus to engineering a “soft landing” from full tilt support for the economy, with the first central bank interest rate hike since 2018 likely next week at its two-day policy meeting. Thereafter, the Fed plans to further withdraw its easy-money stance by shrinking its asset holdings, with an aim to bring inflation closer to its 2% annual target from 7.5% in January.

The path could be complicated by soaring oil and other commodity prices following Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine two weeks ago, resulting Tuesday in the Biden administration banning Russian oil, liquefied natural gas and coal imports.

Read: Biden bans Russian oil imports over Ukraine invasion as he warns gasoline prices will rise further

Also, the above chart shows that investors and the Fed have yet to experience a period of significant balance sheet reduction.

As Al-Hussainy put it: “We have a good idea of how expanding the balance sheet

works when the economy is in distress.” But our understanding “is less clear” when the Fed draws down its balance sheet, in part, because it generally would be happening in a growing economy. The pandemic also cut short its prior attempt.

He now sees three paths for the Fed to shrink its holdings, not all of which are expected to add to market turmoil:

- Runoff: Since last summer, Fed officials were getting ready to slow the $120 billion in monthly pandemic-era bond purchases, with March set as a target end date. The Fed now can opt to “do nothing,” Al-Hussainy said, since the Fed focused on buying shorter-term bonds. “With about one quarter of the balance sheet coming due within 2½ years, it would reduce the balance sheet by just allowing holdings to roll off organically as the debt matures.”

- Change what it owns: The housing market has gotten red-hot, and potentially dangerous in parts of the country during the pandemic. The Fed would “very much like to get out of the agency MBS market altogether,” according to Al-Hussainy, and it could choose to cut its exposure in the sector over time.

- Sell long-term bonds: The Fed could also sell longer Treasury bonds that mature in seven to 20 years, using proceeds to buy shorter-term debts to help steepen the yield curve. Or it could sell 15- to 30-year MBS, although it hasn’t tried either before, and those moves “would be considered quite disruptive.”

Even so, Al-Hussainy tells investors to keep and eye on what the unwinding path signals in terms of future increases to the short-term fed-funds rate, “which would have the most direct impact on fixed-income assets.”

U.S. stocks SPX,