Xi’s Shanghai lockdown and Putin’s Ukraine invasion are screwing up inflation’s return to normal

Inflation just keeps going up.

The U.S. inflation rate rose 8.5% in March, with the prices of food, gas, and housing going up the most. Before last summer, those kinds of numbers hadn’t been seen in the U.S. in more than four decades, but the crucial gauge of inflation, the consumer price index, has kept setting new records since. It was supposed to go down as the pandemic eased, but about that…

The inflationary surges that began hitting the U.S. economy in 2021 were driven by shortages of semiconductors that raised prices for cars and electronics. At the time, economists were convinced that inflation would peak around 7% for the first few months of 2022 and then begin easing throughout the year as pandemic-era spending habits faded and supply networks returned to normal.

“A year from now, as the pandemic recedes, inflation will be low enough that we won’t be talking about it,” Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, wrote in an op-ed for CNN Business last November.

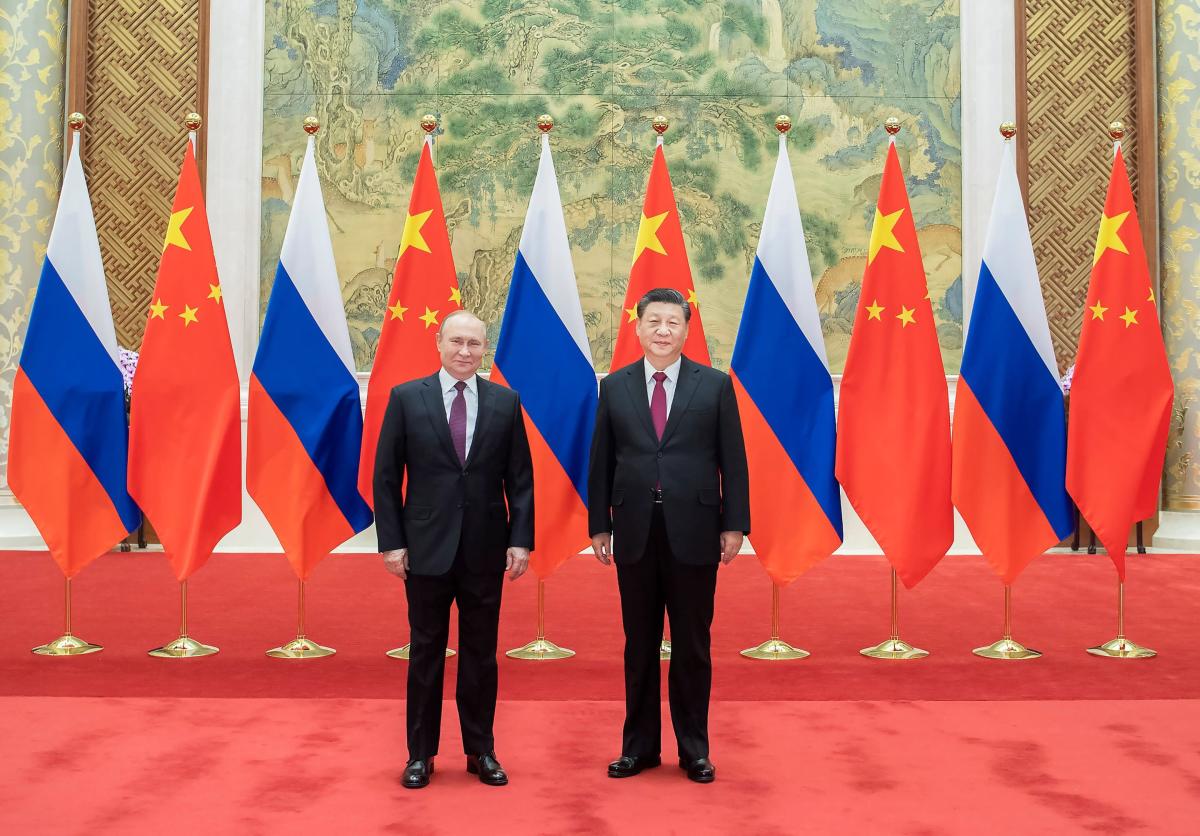

But in early 2022, two sudden events scrambled international markets and pushed the inflationary pullback further out of reach: Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, and the COVID lockdowns in China.

Neither shows signs of abating anytime soon.

The war in Ukraine

Seven weeks in, the war continues to strain global markets of critical resources like oil and wheat. And in the U.S., energy prices have borne the brunt of the war’s economic consequences.

Unlike Europe, which remains heavily reliant on Russian gas and oil imports, the U.S. purchased very little oil or gas from Russia. But markets like oil are global, and a supply interruption affects everyone.

On an average day in 2021, Russia was exporting 4.7 million barrels of oil and nearly 9 trillion cubic feet of natural gas—the world’s largest exporter by volume of both gas and all oil and petroleum products.

Since the war began, the world has been slowly moving to cut Russian energy imports out of the global supply. The U.S. banned Russian oil imports at the beginning of March. The EU then moved to ban all Russian coal imports in early April, while some European countries went further still by cutting off Russian gas supply altogether. Even wealthy nations with large economies have signaled that they will begin banning Russian oil soon, with the U.K. planning on doing so by the end of the year.

While targeting oil and gas is critical to hurting Russia, it has also been painful for U.S. consumers. Prices at the gas pump have been steadily rising for weeks, currently sitting at $4.27 per gallon, $1.32 more than a year ago. In some parts of the country, prices even went as high as $6 per gallon at the end of March.

The Biden administration has been pulling out all the stops to keep gas prices in the country as low as possible, including a record-breaking release from the country’s strategic oil reserve, waiving EPA regulations to allow the sale of different types of fuel, and even setting aside his feud with the U.S. oil industry to push for more domestic production.

For Biden and his party, political aspirations hinge on keeping energy prices manageable.

But while the war in Ukraine rages on and the West continues its search for alternative sources to replace Russian oil and gas, prices are likely to stay volatile and are a big part of the current inflation numbers.

The war has already changed the calculations surrounding inflation. Before the invasion, a group of Swiss firms published their expectation that prices would rise globally 2.37% over the next year. After the war broke out, the number was revised to 2.75%.

In the U.S., Biden has claimed that 70% of price surges are due to the war and “Putin’s price hike” on gas, although the U.S. Labor Department, which publishes monthly data on inflation, has said that the surge in gasoline prices accounts for around half of the inflation rise.

Shanghai’s COVID lockdowns

While the war has been wreaking havoc on energy prices for weeks, the nearly complete shutdown of manufacturing and shipping from one of China’s most strategic ports has added another layer of disruption to the U.S. inflation crisis.

Shanghai, the epicenter of China’s commerce and a manufacturing behemoth, is in the midst of the largest COVID-19 outbreak in the city’s history. Over 23,000 positive cases were confirmed in the city on Friday, bringing the total number of cases to 303,000 since March 1.

It is a remarkable turnaround from what had long been seen as one of the world’s COVID success stories. For two years, China was able to keep the virus mostly under control, with President Xi Jinping insisting on strict border entry requirements.

Some previous lockdowns completely immobilized cities for weeks on end whenever new cases emerged. The lockdown in Shanghai has proved to be more flexible, with some restrictions lifted in residential areas despite record-high caseloads. But commercial areas, workplaces, and factories remain closed.

Since March, the more contagious Omicron variant and other recent strains have broken through China’s defenses. In the process that has brought Shanghai’s enormous manufacturing industry to a standstill, as well as the world’s largest container port located just outside the city.

The lockdown is not limited to Shanghai and has hit several key tech manufacturing plants, with one Tesla gigafactory shutting down in March, delaying the production of nearly 40,000 cars. Production plants for tech companies are littered around Shanghai, and the lockdown has also forced shutdowns at an iPhone maker based in the city.

A top executive for Huawei, one of China’s largest electronics companies, recently warned that the lockdown could lead to “massive losses” for the global auto and electronics sector.

In addition to manufacturing shortages, the lockdown is also forcing a shutdown of operations at the city’s crucial port. This week, a shortage of workers forced 477 bulk cargo ships to wait just outside of the city’s main port to unload their cargoes of grains and metals.

Longer wait times and supply-chain issues have been a staple of this inflationary era, and an ongoing lockdown affecting the port of Shanghai will only aggravate the crisis.

Even though the lockdowns could cost the city nearly 4% of its annual GDP, and with Shanghai residents literally screaming from their rooftops, Xi Jinping is doubling down on his zero-COVID policy, saying this week that the approach “cannot be relaxed.”

China’s lockdowns are expected to carry a significant inflation risk for a number of commodities, and price hikes are already hitting electronics and automobiles that depend on manufacturing in China.

A Toyota executive, speaking at the New York Auto Show this week, warned that car prices will likely remain elevated and probably go even higher “well into 2023,” citing carmakers’ inability to manufacture enough to keep up with demand.

Should the lockdown continue, prices for electronics and cars will surely rise in the U.S., and with slower loading times and delayed shipping from one of the world’s busiest ports, it seems that inflation will remain high as long as extraordinary events in Shanghai and Ukraine continue.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com