Europe’s Green Deal requires massive amounts of battery metals – study

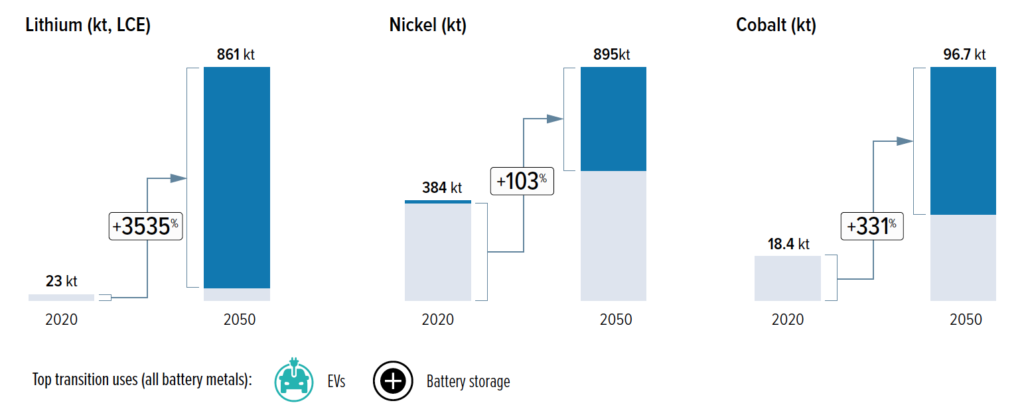

Europe’s battery metals needs until 2050. (Graph by KU Leuven University).

In real numbers, the percentages talk about 4.5 million tonnes of aluminum, 1.5 million tonnes of copper, 800,000 tonnes of lithium, 400,000 tonnes of nickel, 300,000 tonnes of zinc, 200,000 tonnes of silicon, 60,000 tonnes of cobalt, and 3,000 tonnes of the rare earths metals neodymium, dysprosium and praseodymium, which is an increase between 700-2,600% from current levels.

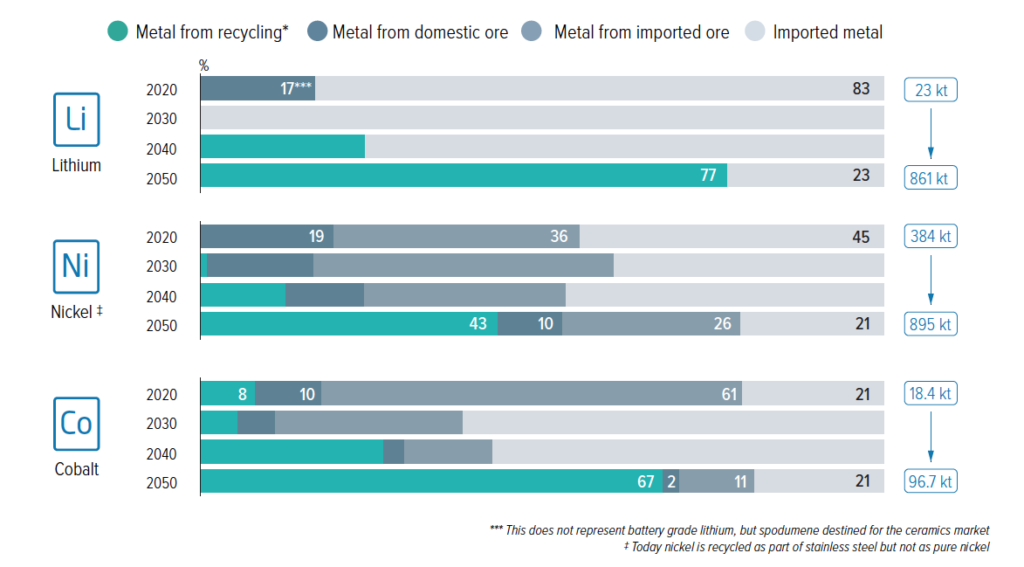

The report also provides some good news. By 2050, 40% to 75% of Europe’s clean energy metal needs could be met through local recycling if Europe invests heavily now and fixes bottlenecks.

“But Europe faces critical shortfalls in the next 15 years without more mined and refined metals supplying the start of its clean energy system,” the dossier points out. “Progressive steps will be needed to develop a long-term circular economy, which avoids a repeat of Europe’s current fossil fuel dependency.”

Supply problems by 2030

According to the study, Europe could face problems around 2030 from global supply shortages for five raw materials, namely, lithium, cobalt, nickel, rare earths, and copper. EU primary metals demand will peak around 2040; thereafter, increased recycling will help the bloc towards greater self-sufficiency, assuming major investments are made in recycling infrastructure and legislative bottlenecks are addressed.

The report sees coal-powered Chinese and Indonesian metal production dominating global refining capacity growth for battery metals and rare earths. It also points out that Europe relies on Russia for its current supply of aluminum, nickel and copper.

Within this context, the authors of the paper recommend that Europe starts building solid bridges with proven responsible suppliers managing their environmental and social risks. It also questions why the bloc has not yet followed other global powers like China in investing in external mines to drive ESG standards directly.

“A paradigm shift is needed if Europe wants to develop new local supply sources with high environmental and social protections,” the document states. “Today, we don’t see the community buy-in or the business conditions for the continent to build its own strong supply chains. The window is narrowing; projects really need to be taken forward in the next two years to be ready by 2030.”

The study says there is theoretical potential for new domestic mines to cover between 5% and 55% of Europe’s 2030 needs, with the largest project pipelines for lithium and rare earths. However, most announced projects have an uncertain future despite Europe’s comparatively high environmental standards, struggling with local community opposition and permit challenges, or relying on untested processes.

“Europe would also need to open new refineries to transform mined ores and secondary raw materials into metals or chemicals,” the dossier suggests.

The issue these days is that the current energy crisis makes new refining investment challenging, as skyrocketing power prices have already caused the temporary closure of nearly half the continent’s existing refining capacity for aluminum and zinc, while production has increased in other parts of the world.