What the death of the penny teaches us about the future of money

Policymakers have started talking openly about the possibility of all physical money going the way of the copper coin

Article content

Take one, leave one: the penny had been a regular part of Canadian cash for well over a century, sitting at the bottom of wallets, gracing tip jars, and being fished out of pockets to support local charities.

Advertisement 2

Story continues below

Article content

That was until the federal government decided to take the penny out of circulation in the 2012 federal budget, following a finance committee study that deemed the coin too expensive to produce and no longer necessary. The late finance minister Jim Flaherty pressed the last penny on May 4 of that year, marking the end of an era.

A decade later, Canada could be on the cusp of a far more radical shift in payments, as policymakers talk openly about the possibility of all physical money going the way of the copper coin. If that happens, lessons from the demise from the penny could help smooth the transition. Killing off a coin that most people have stopped using sounds simple, but it isn’t.

“I think it will be absolutely valuable going forward as less coins circulate,” Marie Lemay, chief executive of Royal Canadian Mint, said in an interview. “You need that intelligence.”

Advertisement 3

Story continues below

Article content

The ten-year anniversary of the decision of former prime minister Stephen Harper’s government to end the penny comes at a time when money is quickly going digital and Canadians are less likely to carry cash and coin around with them.

Last year, the Bank of Canada signalled it was keeping an eye on the situation, as it accelerated its research on digital currencies, including a virtual dollar. “The world has been changing even faster than we expected,” said deputy governor Timothy Lane. “One scenario we have been watching is whether a sharp decline in the acceptance of cash reaches a tipping point in Canada,” he said. “We’ve already seen that as societies and economies modernize, cash has been losing ground to digital methods of payment — around the world and here at home.”

Advertisement 4

Story continues below

Article content

The central bank’s senior deputy governor, Carolyn Rogers, echoed this sentiment this week, saying that while the shift to digital payments is largely demographic, she could nonetheless see Canadians giving up cash altogether. “We can foresee a future where there is only digital currency, that’s possible,” Rogers said in an interview on May 3. “So, there ought to be a digital Canadian dollar in that case, and so that’s what we’re working on.”

The coin management system that helped guide Canadians into a post-penny economy is now actively helping all Canadians transition into the digital economy.

An important lesson from the penny’s demise is that some people cling to a unit of payment even as the majority moves on. That matters, because a central tenet of government tender is accessibility and universality. In other words, if a critical mass of Canadians want to keep using cash and coins, they should be able to do so. The Mint, thanks to its experience with slowly taking the penny out of circulation, has learned how to orchestrate a smooth transition. Lemay said her agency has become expert at pinpointing where there is demand for coins, and then ensuring there is enough supply in those places.

Advertisement 5

Story continues below

Article content

“You need to have that view into where (demand is) and you need that possibility to move them around to be able to make sure that people access coins and that we do it in a responsible and efficient manner,” she said.

Vibrant history

But before the penny became a case study in how the Mint will help usher in a world of digital payments, the coin had its own vibrant history that shows why some may have been reluctant to see it go.

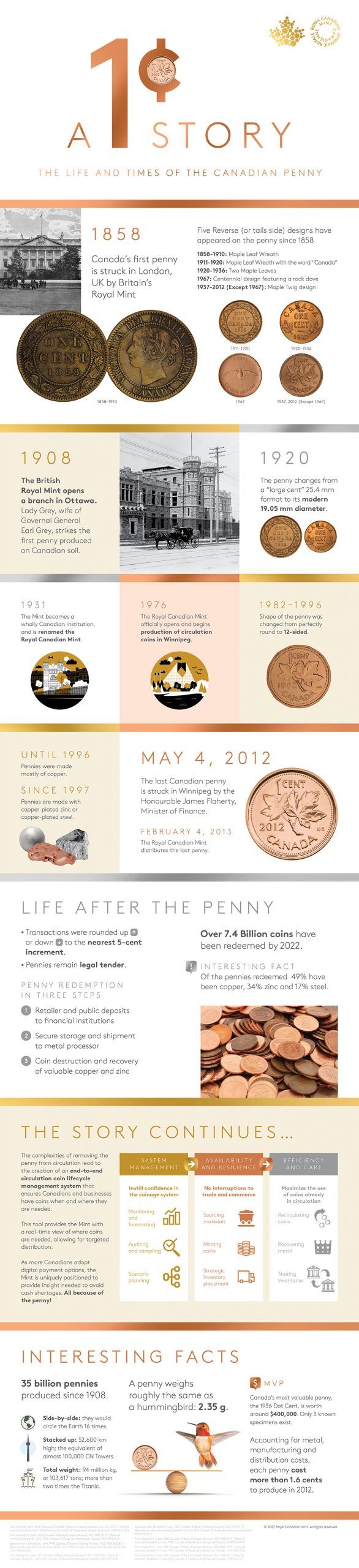

When the penny was first minted in 1858, it was struck in the U.K. by the British Royal Mint, adorned by a maple leaf wreath. It wasn’t until the 1910s when the name “Canada” crossed its face a few years after the British government opened a Royal Mint in Ottawa.

Over the years, the design and makeup of the cent went through various iterations, including the 1936 “Dot Penny,” a collector’s item that came about as Edward VIII abdicated that same year and Canadian coin-makers were in the process of creating the new Royal design that would adorn the 1937 coin.

Advertisement 6

Story continues below

Article content

The work on a new design for Edward VIII or his successor George VI hadn’t yet been finished, so to avoid a production gap, designers went with the likeness of the previous monarch, George V. The coin also featured the 1936 date with one distinguishing feature: a small dot beneath the date. Due to an over-production of pennies, most of these coins were melted down and only three remain — one of them trading for $400,000 at auction in 2010.

“The 1936 Dot Penny is a good illustration of the value of our coin management system,” said Mint spokesperson Alexandre Reeves. “Without adequate data and market intelligence, officials at the time could not estimate demand correctly. When the new George VI pennies were ready in late 1937, the still unused 1936 cents became obsolete. Think of it as a kind of sobering lesson.”

Advertisement 7

Story continues below

Article content

‘Extremely valuable for Canada’

Despite its various appearances, the penny maintained its role as the most fractional legal tender in the Canadian economy. The Royal Canadian Mint, which became a wholly Canadian institution and earned its name in 1931, officially opened up its Winnipeg coin production and circulation centre in 1976.

After the penny left Canadian circulation, it changed payments countrywide, as transactions were rounded up or down to the nearest five-cent level. It also evolved the Mint’s coin-management system.

Lemay said it was because of Canada’s unique approach to coin management that allowed for the removal of billions of coins from circulation relatively painlessly.

“We work with the financial institutions, the armoured car carriers, and we monitor the coin use across the country in real time, and then we use that information to estimate the requirements we forecast,” Lemay said. “That system was in place when the penny removal happened and ten years later, it has been enhanced and it will continue to be extremely valuable for Canada as we move to a world where there will be more and more digital payments.”

Advertisement 8

Story continues below

Article content

The Mint had to iron out details months in advance to pull the coins out of circulation, ultimately leveraging a network of armoured trucks to collect billions of pennies and flatten them to extract their base metals, rendering them unusable as legal tender in a process called “demonetization.”

More than 7.4 billion coins have been redeemed to date, the bulk of which had been brought in during the first three years after the coin was taken out of circulation.

Years after this process started, Lenard Cheung, senior director of the circulation team at the Mint, reflected on how the penny’s life and death illustrated Canadians’ relationships with coins. “In the olden days, a penny could buy a lot,” he said. “Now, we’re just seeing it used less frequently for that just because of the purchasing power.”

Advertisement 9

Story continues below

Article content

Cheung added the Mint and the Bank of Canada had been gauging how Canadians use money through a series of surveys, finding that the population’s relationship with cash varies greatly from demographic to demographic. For instance, Canadians with lower incomes are more likely to use cash than those with higher incomes, and rural communities are more cash-reliant than city folk.

Leave no one behind

Keeping track of attitudes towards coins also informs the Mint’s mandate of providing enough coins to the communities that rely on them the most. These surveys became particularly important for mapping out a post-pandemic cash economy, and whether Canadians would still rely on cash and coins to the same degree, said Canadian circulation senior manager Anthony Rotondo.

Advertisement 10

Story continues below

Article content

The acceleration of e-commerce and the digitization of money during the pandemic may have given the impression that the country was moving closer to a cashless society. However, that may not be the case: Rotondo noted roughly eight out of ten Canadians surveyed still plan to use cash after the pandemic. “We like to hone in on those couple of key points, specifically when it comes to cash usage,” he said. “Those are going to be very good indicators, once we navigate out of the pandemic, of what we can expect.”

-

Crypto has potential but it won’t usurp the loonie: Bank of Canada governor

-

Bank of Canada’s Lane sees major role for private sector in making central bank digital currencies flourish

-

Bank of Canada taps quantum computing startup to tackle complex financial problems

-

What Biden’s executive order on crypto means for Canada’s crypto ecosystem

Advertisement 11

Story continues below

Article content

Lemay, the Mint’s chief executive, said the shift to digital payments is similar to what happened when Canada gave up on the penny. She added that it’s the Mint’s role to support Canadians in this transition by ensuring the cash-dependent Canadians will have access to it for as long as they need it. There are a lot of Canadians who no longer have cash in their pockets, “but a lot of Canadians do, so we have to make sure that we’re not leaving anybody behind,” she said.

Understanding the penny’s past and how the country moved on from the copper coin is another step in the direction heading towards what relationship Canadians will have with their money in the future.

“I think that the coexistence of cash and digital payments and currency is the future and will allow the country to move forward and (these are) actually exciting times,” Lemay said.

• Email: [email protected] | Twitter: StephHughes95

Advertisement

Story continues below