Here’s why the stock market gets ‘squirrelly’ when bond yields rise above 3%

Stock-market investors seem to get jittery when the 10-year Treasury yield is trading above 3%. A look at corporate and government debt levels explains why, according to one closely followed analyst.

“Neither the Federal government nor businesses can afford +10% Treasury yields, common in the 1970s. That’s why the ‘Fed Put’ is all about Treasury yields now, and why equity markets get squirrelly over 3%,” said Nicholas Colas, co-founder of DataTrek Research, in a Tuesday note.

Investors have talked of a figurative Fed put since at least the October 1987 stock-market crash prompted the Alan Greenspan-led central bank to lower interest rates. An actual put option is a financial derivative that gives the holder the right but not the obligation to sell the underlying asset at a set level, known as the strike price, serving as an insurance policy against a market decline.

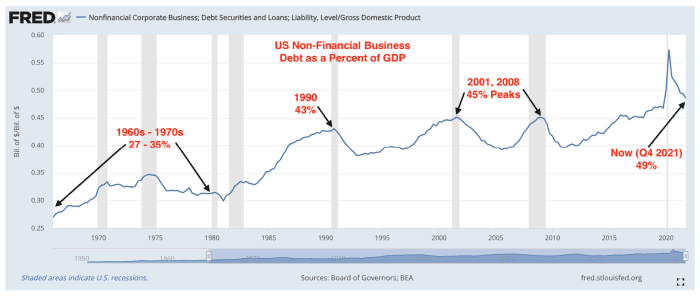

Colas noted that U.S. government public debt to gross domestic product is 125% now, versus 31% in 1979. Business debt is equal to 49% of GDP versus 35% in 1979, he said (see chart below).

U.S. nonfinancial business debt (both bonds and loans) as a percent of GDP.

Board of Governors, BEA, DataTrek Research

Corporate debt-to-GDP is 40% higher than in the inflationary/high interest-rate environment of the 1970s, Colas said. That’s offset by much higher equity valuations for public and larger private companies than the 1970s, he noted, observing that while issuing stock to pay down debt may not be a favorite choice for CEOs or shareholders, it can be done if debt-service costs get out of hand.

Rising interest rates, of course, mean higher debt-service costs. And public and corporate debt is now a much larger part of the U.S. economy than in the 1970s, which must figure into any discussion of inflation-fighting monetary policy moves, he said. Meanwhile, a sharp selloff in Treasurys has driven up yields, which move opposite to price, with the rate on the 10-year note TMUBMUSD10Y,

The S&P 500 SPX,

The damage that could be done by the 10%+ Treasury and corporate yields of the 1970s would be much larger now, Colas said, arguing that’s why the “Fed put” has shifted from the stock market to the Treasury market.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his fellow policy makers “know that they must keep structural inflation at bay and Treasury yields low. Much, much lower than the 1970s,” he said.

According to Colas, that helps explain why U.S. equity markets get shaky when Treasury yields hit 3%, as was the case in the fourth quarter of 2018 and now.

“It’s not that a 3% cost of risk-free capital is inherently unmanageable, either for the Federal government or the private sector. Rather, it is the market’s way of signaling the manifold uncertainties if rates don’t stop at 3%, but instead keep rising,” he said.