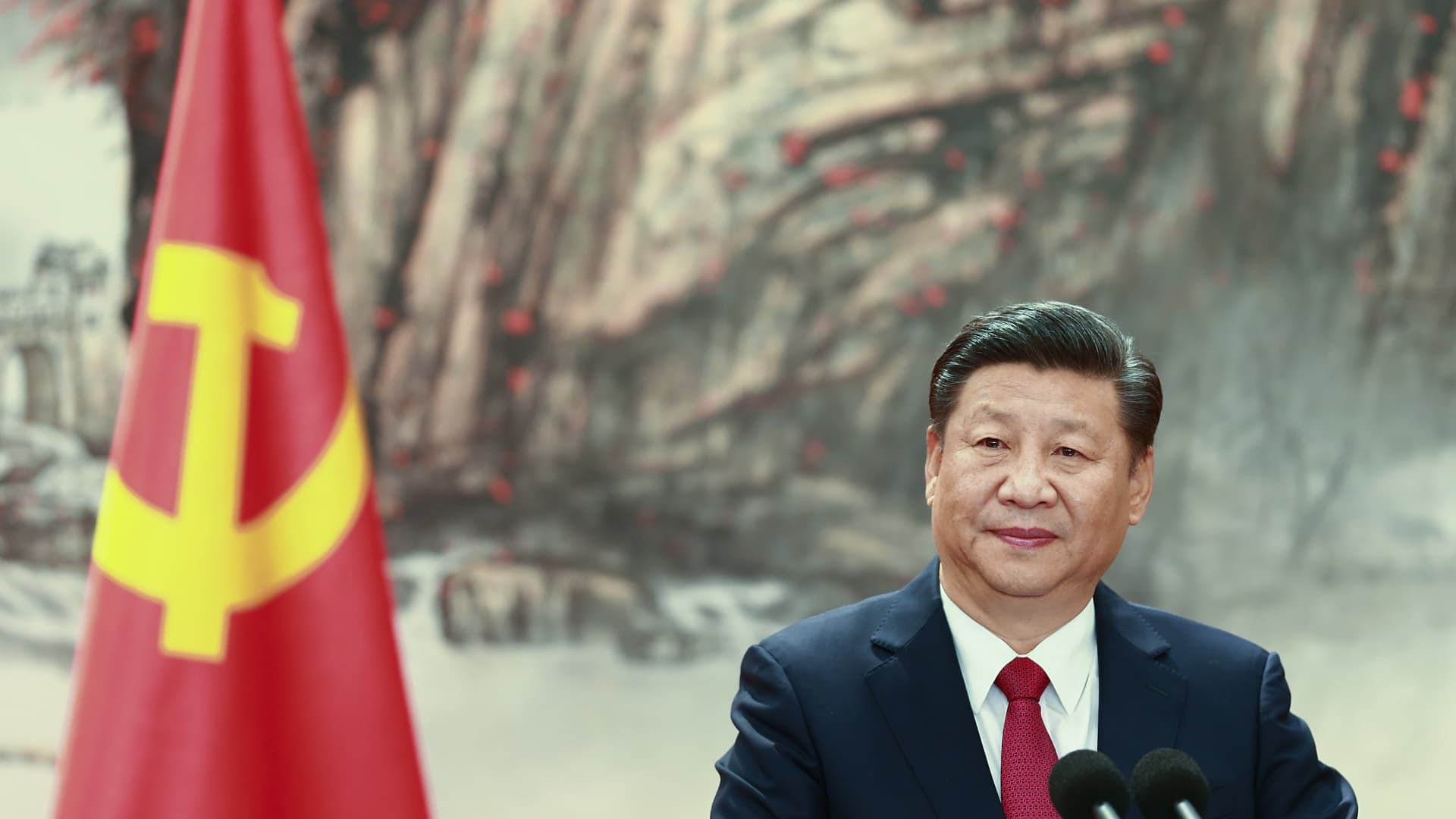

For President Xi Jinping, dispatching his special envoy to Europe for a three-week charm tour was just one of many acts of high-stakes damage control ahead of the 20th Chinese Communist Party Congress this autumn.

Xi’s economy is dangerously slowing, financing for his Belt and Road Initiative has tanked, his Zero Covid policy is flailing, and his continued support of Russian President Vladimir Putin hangs like a cloud over his claim of being the world’s premier national sovereignty champion as Russia’s war on Ukraine grinds on.

Few China watchers believe Xi’s hold on power faces any serious challenge, but that’s hard to rule out entirely given how many recent mistakes he’s made. So, Xi’s taking no chances ahead of one of his party’s most important gatherings, a meeting designed to assure his continued rule and his place in history.

European business leaders understood that as the context for their recent meetings with Wu Hongbo, the special representative of the Chinese government for European affairs and former UN Undersecretary General. His message was a similar one at every stop: Belgium, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Germany, and Italy.

“The Chinese want to change the tone of the story, to control the damage,” said one European business leader who asked to remain anonymous due to his Chinese business interests. “They understand they have gone too far.”

The businessman described Wu, with his fluent and fluid English, as one of the smoothest, most open, and intellectually nimble Chinese officials he’s met. At every stop, Wu conceded China had “made mistakes,” from its handling of Covid-19, to its “wolf warrior” diplomacy, to its economic mismanagement.

His trip came as concerns in China have grown about “losing Europe” in the wake of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

The public mood has shifted sufficiently to have Finland and Sweden knocking on NATO’s door, and the European Union this week embracing the prospect of Ukraine’s membership candidacy. Wu’s visit was also something of a mop-up operation following a failed visit by Chinese official Huo Yuzhen to eight central and east European countries. In Poland, he was refused a meeting with government officials.

Germans and their political leaders — Europe’s most significant target for Chinese diplomats and business — are raising new questions about everything from investment guarantees for German business in China to specific projects like VW’s factory in Xinjian province, home of human rights abuses against the primarily Muslim Uyghur population.

Though Wu addressed Putin’s war in Ukraine only indirectly, his message was designed to reassure Europeans that they are preferred partners, as opposed to the United States. His bottom line: China will always be China, a country of growing significance and economic opportunities for Europe.

Yet lost ground in Europe is just one of many gathering problems President Xi faces ahead of his party congress, which will determine the country’s economic, foreign policy and domestic agenda for years to come.

The party congress is likely to provide Xi a third term, a move that follows a 2018 decision to scrap term limits. What’s more likely to reveal the extent of Xi’s power, writes Michael Cunningham of the Heritage Foundation, is whether he can put his allies in key central bodies, primarily the Politburo and the Politburo Standing Committee, as retirement norms ensure considerable turnover.

However the Congress turns out, there is growing talk among China experts about whether we are entering a period of “Peak Xi” or even “Peak China.” There’s growing evidence that he and the country he represents (and his approach has been to make the two inseparable) have reached the height of their influence and reputation.

Nothing will determine the outcome more than how Xi manages China’s economy, which is the foundation for the country’s far-reaching global influence as well as the Communist party’s domestic legitimacy.

Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, one of the keenest China-watchers anywhere, sees China’s economic prospects weakening due to a chain of factors. They include at least 10 Chinese property developer defaults, and Xi’s crackdown on China’s technology sector, which has cost it $2 trillion in market capitalization of its 10 biggest tech companies over the past year.

Moreover, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has sent energy and commodity prices soaring and has snarled supply chains, “terrible news for the world’s largest manufacturer, exporter and energy-consuming economy,” Rudd wrote recently in The Wall Street Journal. Add to this Xi’s insistence on China’s Zero Covid strategy, which led to mass lockdowns.

Rudd concludes that this combination of factors is enough to make Xi miss his 5.5% growth target and perhaps even grow more slowly this year than the United States. “For Mr. Xi, failing to reach the target would be politically disastrous,” writes Rudd.

Xi’s damage control on the economic front has included fiscal and monetary stimulus and infrastructure spending to grow domestic demand. A recent meeting of the Politburo also suggested some coming relief from the regulatory crackdown on China’s tech sector.

Yet none of that will be enough to reverse Xi’s cardinal sin, and that was his dramatic pivot to stronger state and party controls.

Writing in Foreign Affairs, the Atlantic Council’s Daniel H. Rosen, who is a founding partner of Rhodium Group, argues, “China cannot have both today’s statism and yesterday’s strong growth rates. It will have to choose.”

Adds Craig Singleton this week in Foreign Policy, “China’s fizzling economic miracle may soon undercut the (Communist party’s) ability to wage a sustained struggle for geostrategic dominance.”

There’s not much time left for damage control before Xi opens his party Congress in the Great Hall of the People. He’s likely to get the vote he wants, but that won’t solve the larger problem. It has been his leadership and decision-making that have generated China’s challenges, and he’ll have to correct course if he is to restore economic growth at home, revive his international momentum and avoid “Peak Xi.”

— Frederick Kempe is the President and Chief Executive Officer of the Atlantic Council.