The view through the window: Three Canadian astronauts weigh in on innovation, climate and future of spaceflight

Dave Williams, Chris Hadfield and Robert Thirsk say the ISS offers the world a model for collaboration

Article content

“The space station, high above, is a microcosm — an international collection of people living in a finite area with finite resources, just like the planet below,” Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield once wrote. He knows the International Space Station (ISS) well. He’s been up three separate times: 1995, 2001 and 2012, eventually becoming ISS commander on his final mission.

Advertisement 2

Story continues below

Article content

The station’s limited resources — coupled with the harsh environment of space — create the perfect conditions for innovation. For one, the ISS uses closed-loop heating and water systems so the astronauts don’t need to depend on external sources. “You flush the toilet, and yesterday’s coffee becomes today’s water,” astronaut Dave Williams said, with a laugh.

The crew members, who all hail from different parts of the world, offering a range of technical and professional expertise, have to work together to maintain and operate the station’s “habitability systems.”

Innovation on Earth tends to follow the drumbeat of space. A website called NASA Spinoff documents the space technologies that have found their way back to Earth, which include memory foam and freeze-dried food. Arguably, the most important space export by far is the strong tradition of collaboration between the international crew members, which transcends cultures and political affiliations.

Advertisement 3

Story continues below

Article content

That’s exactly what we need to address the Earth’s most pressing issues, namely, the climate crisis, Williams said. “It is the greatest lesson of the International Space Station: the opportunity to learn how effective collaboration actually works.”

The growing space economy, now worth US$424 billion, will create an abundance of new jobs linked to climate innovation, he added. “You’re developing technologies, many of which are going to help with the greening economy and … enable us to have less environmental impact.”

Williams went to space in 1998, and again in 2007, setting the record for the most spacewalks completed by a Canadian astronaut. His biomedical tech startup, Leap Biosystems Inc., is just one example of the ways in which space technology can be used on Earth.

Advertisement 4

Story continues below

Article content

The company is experimenting with “holoportation,” a technology developed by Microsoft Corp., which allows someone wearing a headset on Earth to appear as a hologram on the ISS. It reminds Williams of Star Trek. “Beam me up, Scotty!” he said.

The technology is still in its infancy, but he hopes it will one day be used to deliver medical care to remote corners of the world.

It is the greatest lesson of the International Space Station: the opportunity to learn how effective collaboration actually works

Dave Williams

Lately, Williams has been considering another terrestrial application for space technology. In his forthcoming book on planetary stewardship, he asks: Can we live as collaboratively and sustainably on Earth as we do on the ISS?

The globe, like the ISS, is a closed loop. It depends on “finely tuned connections between the land, oceans, atmosphere, the freshwater cycle, flora and fauna,” astronaut Robert Thirsk wrote in his blog.

Advertisement 5

Story continues below

Article content

He went to the ISS in 1996 and 2009, setting the Canadian record for the most time spent in space, at 204 days and 18 hours. “The planet is whole. And it’s integrated,” he said in an interview.

The planet is whole. And it’s integrated

Robert Thirsk

From the ISS, astronauts can watch as natural events on one side of the world affect the other. Smoke plumes from forest fires in Siberia drift over to North America, lowering the air quality there. A small, unassuming atmospheric depression in the southern Atlantic grows into a Category 4 or 5 hurricane, affecting residents and businesses along the Gulf Coast.

Thirsk said that a mutant virus originating in Asia and wreaking havoc on the world may seem unbelievable to most, but “for an astronaut, that is very easy to appreciate.”

Advertisement 6

Story continues below

Article content

‘A thin veil of atmosphere’

The astronauts marvel at natural phenomena. Travelling at 8 km/s, or 25 times the speed of sound, the ISS completes a single orbit of the globe once every 90 minutes, meaning that its occupants witness a sunrise and sunset every 45 minutes.

“The view out the window takes everyone by surprise,” Thirsk said. “There’s (something) about seeing the Earth with your naked eyeball and seeing it from above. The privileged position that you have, somehow, it just amplifies the beauty and majesty of it all.”

Earthbound astronauts speak about the planet with wonder. Williams called it “a beautiful blue oasis cast against the infinite void of space.” Describing this image to people back home, he said, is perhaps a lesser-known mission of space travel.

Advertisement 7

Story continues below

Article content

The view of the Earth from space was “personally transformative,” Thirsk wrote on his blog. “Viewed from afar, our marbled-blue planet is alone for hundreds of millions of kilometres, surrounded by nothing but void.”

Hadfield said he was fortunate enough to watch the world change seasons, snow shifting from one hemisphere to the other.

“I got to see the world, in effect, take one breath out of 4.5 billion breaths … There has been life, uninterrupted, on Earth, for four billion years,” he said. “That’s really optimism-building. Life isn’t going anywhere. The world isn’t going anywhere. The question is: How good a quality of life do we want for people, and how sustainable do we want it to be?”

Every day, astronauts on the ISS are confronted with the reality of the ecological crisis. Mining cuts jagged strips into the Earth. A smear of pollution obscures major cities. The Amazon rainforest is clear cut and burnt down to create room for agriculture, the smoky pall drifting across the Atlantic to impact the air quality in Africa.

Advertisement 8

Story continues below

Article content

“There is just a thin veil of atmosphere around the planet that is protecting the inhabitants below from the vacuum of space, the ultraviolet and ionizing radiation, the extremes of temperature,” Thirsk said.

That, he said, is the only thing that makes the difference between a barren planet and one that teems with life.

“Realizing that frail, vulnerable planet down below is our home makes me even more diligent in preserving its existence,” he added.

If everyone in the world could see that view, the astronauts said, the question would no longer be “if” we will solve the climate crisis, but “when.”

An orbital perspective

Astronauts are not the only ones keeping an eye on emissions from space. Private satellite companies are jostling for market share in the expanding orbital environmental monitoring industry.

Advertisement 9

Story continues below

Article content

Montreal-based company GHGSat Inc., which sends satellites into space to track methane emissions, on June 15 said one of its satellites had detected 13 plumes of methane emanating from a coal mine in Russia in January. It was the largest methane leak the company had ever detected.

Compared to carbon dioxide, methane is 25 times as effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere.

GHGSat has a track record of calling out serious offenders. In 2019, its satellites helped pinpoint methane leaks in Turkmenistan, which were releasing emissions equivalent to 250,000 gas-powered cars. In 2021, the company spotted a methane plume coming from a landfill in Pakistan.

The public sector is getting involved as well. This January, Canada committed $8 million to environmental monitoring via satellites as part of the Canadian Space Agency’s smartEarth initiative.

Advertisement 10

Story continues below

Article content

“It’s an emerging area. It’s really going to change the way we quantify and understand emissions,” said atmospheric scientist Ray Nassar, one of the pioneers of environmental observation via satellites. “You can’t manage what you can’t measure.”

In 2017, he led the first study to use satellites to quantify carbon emissions, with results precise enough to pinpoint the source of emissions to a single power plant.

Emissions can be tracked from the ground as well, but “satellites allow enhanced transparency,” Nassar said. “Under the Paris Agreement, countries are pledging to reduce their emissions. They’re not actually obligated to do that. They’re obligated to report. We want to have the ability to verify emissions reductions.”

Advertisement 11

Story continues below

Article content

Satellites will paint a more cohesive picture than traditional measurement techniques.

“There is a network of ground-based measurements for greenhouse gases across the world,” Nassar said. “But the thing about those measurements is it’s so unequally distributed … if you ever want a global picture, it’s really lacking. And satellites can do that.”

The Committee on Earth Observation Satellites (CEOS) is trying to get the companies that send out these satellites to work together and share data, to create a sort of “constellation” of satellites in space, he said.

As the green transition progresses, collaboration will be key, both in space and on Earth. The astronauts were divided on the solutions to the climate crisis, but agreed that addressing the issue would require precise political co-operation, similar to what already exists on the ISS. Co-operation on the ISS is next to perfect. It has to be.

Advertisement 12

Story continues below

Article content

“Everyone on the space station, their lives are in each other’s hands,” Hadfield said. “If anybody makes a mistake, everyone else dies.”

The ISS astronauts are united by a common purpose, he added, and by the “ever-present danger of being there.”

Everyone on the space station, their lives are in each other’s hands

Chris Hafield

But even on the ISS, collaboration is not always easy, Williams said. He likened it to disputes among family members. On a planetary scale, however, the disagreements are more complex and involve more people, such that it is difficult to find solutions that work for all governments.

‘Humans first’

Collaboration on the ISS is helped because political divisions are muted.

“We’re just a bunch of people up there,” Hadfield said.

Thirsk echoed a similar sentiment: “All the crews from all the nations, the cultures that are represented, have a single-minded focus on accomplishing the mission objectives.”

Advertisement 13

Story continues below

Article content

To facilitate communication, astronauts aboard the ISS need to speak English and Russian, with English serving as the interstellar lingua franca.

Even so, “when you’re on board the space station as a crew member, most of us tend to think of ourselves as humans first,” he said.

Williams considers himself a Canadian, but also a citizen of the Earth, a resident of a “global village.” The borders between countries, he pointed out, are invisible from space.

We’re just a bunch of people up there

Chris Hadfield

“If you’re sitting in Montreal, or sitting in Toronto, you have a really skewed view of the world,” Hadfield said. “It’s very local.” As a result, “a lot of the decisions that we make and some of our elected officials make are parochial in nature.”

Citizens tend to focus on their own communities. What they can see, where they can travel. But “when you get into space, you see Earth as a planet,” he said.

Advertisement 14

Story continues below

Article content

The astronauts said that, upon returning to Earth, their political perspectives had evolved. For instance, Thirsk said that the daily, local news cycle was of little interest. “That’s all noise level to me.” His concerns are now more global, chief among them being nuclear annihilation and the climate.

“I do worry about the motives of some of these world leaders who have created an unstable geopolitical situation,” he said. “I don’t see the older generation showing enough leadership in making the difficult decisions, today.”

-

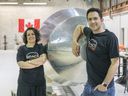

Up, up and away: Space industry startup is using balloons to launch rockets

-

My summer job: Astronaut Roberta Bondar’s dark days sending unlucky moths to their deaths

-

My worst summer job: Chris Hadfield on drumming up business for a waterski school

-

Nova Scotia fishing community divided over proposal to build Canada’s first commercial spaceport

Advertisement 15

Story continues below

Article content

Thirsk expects it will be the younger generation who will ultimately take charge of the climate fight. Williams agreed. Young people, he said, led by activists such as Greta Thunberg, will lead the way.

“It’s really easy to be critical of the lack of collaboration,” he said. “There are areas that, quite clearly, we are not collaborating here on Earth and areas that we are.”

Either way, Hadfield is optimistic that we will find answers. “The same driving, restless intellect that created the problems can minimize and even reverse them,” he once wrote.

If ever we doubt our capacity to collaborate, we need only “look up, morning and night, and watch the space station fly over,” Hadfield said. “It’s a pretty clear example of what we do together when we do things right.”

• Email: mcoulton@postmedia.com | Twitter: marisacoulton

Advertisement

Story continues below