The 60-40 portfolio is supposed to protect investors from volatility: so why is it having such a bad year?

The first half of 2022 has been a historically bad stretch for markets, and the carnage hasn’t been limited to stocks. As stocks and bonds have sold off in tandem, investors who for years have relied on the 60-40 portfolio — named because it involves holding 60% of one’s assets in stocks, and the remaining 40% in bonds — have struggled to find respite from the selling.

Practically every area of investment (with the exception of real assets like housing and surging commodities like oil CL00,

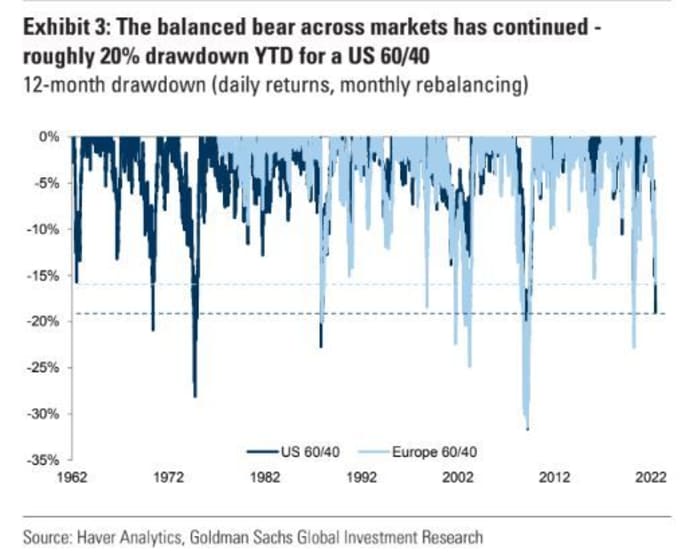

According to analysts at Goldman Sachs, Penn Mutual Asset Management and others, the 60-40 portfolio has performed this bad for decades.

“This has been one of the worst starts to the year in a very long time,” said Rishabh Bhandari, a senior portfolio manager at Capstone Investment Advisors.

Goldman’s gauge of the model 60-40 portfolio’s performance has fallen by roughly 20% since the start of the year, marking the worst performance since the 1960s, according to a team of analysts led by Chief Global Equity Strategist Peter Oppenheimer.

Government bonds were on track for their worst year since 1865, the year the U.S. Civil War ended, as MarketWatch reported earlier. On the equities side, the S&P 500 finished the first half with the worst performance to start a year since the early 1970s. When adjusted for inflation, it was its worst stretch for real returns since the 1960s, according to data from Deutsche Bank’s Jim Reid.

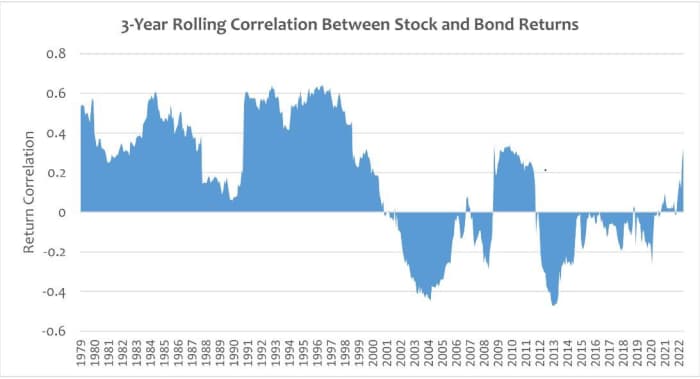

It has been a highly unusual situation. Over the past 20 years, the 60-40 portfolio arrangement has worked out well for investor, especially in the decade following the financial crisis, when bonds and stocks rallied in tandem. Often when stocks endured a rough patch, bonds would typically rally, helping to offset losses from the equity side of the portfolio, according to market data provided by FactSet.

Read (from May): Farewell TINA? Why stock-market investors can’t afford to ignore rising real yields

Matt Dyer, an investment analyst with Penn Mutual Asset Management, pointed out that beginning in 2000, the U.S. entered a 20-year period of persistently negative correlations between stocks and bonds, with the exception of the post-crisis period between 2009 and 2012. Dyer illustrated the long-term correlation between stocks and bonds in the chart below, which shows the relationship started to shift in 2021, before the tandem selling in 2022 began.

The correlation between stocks and bonds, which was negative for decades, has flipped back into positive territory this year. SOURCE: PENN MUTUAL ASSET MANAGEMENT

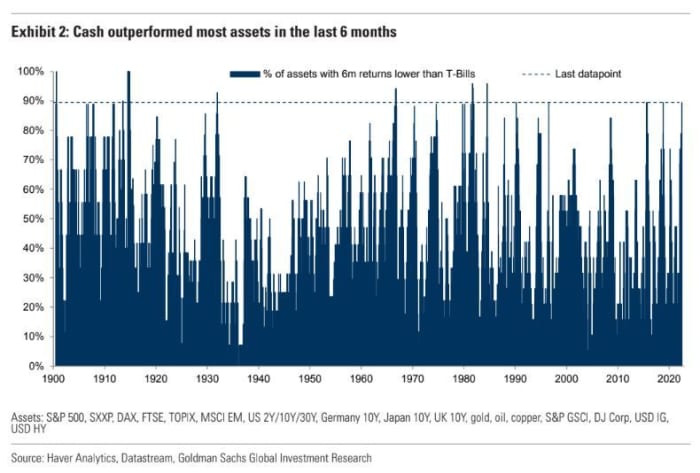

Individual investors don’t typically have access to alternatives like hedge funds and private equity, hence, stocks and bonds typically serve as their most easily investible assets. Those choices, however, have become problematic this year, since individual investors essentially had nowhere to turn, besides cash, or a commodity-focused fund.

Indeed, over the past six months, more than 90% of assets tracked by Goldman have underperformed a portfolio of cash equivalents in the form of short-dated Treasury bills.

Institutional investors, on the other hand, have more options for hedging their portfolios against simultaneous selling in bonds and stocks. According to Bhandari at Capstone, one option available to pension funds, hedge funds and other institutions is buying over-the-counter options designed to pay off when both stocks and bonds decline. Bhandari said options like these allowed his firm to hedge both their equity and bond exposure in a cost-effective manner, since an option that only pays off if both bonds and stocks decline typically is cheaper than a standardized option that pays off if only stocks decline.

Guggenheim’s Scott Minerd has been warning of a dreadful summer ahead, while recommending investors turn to real assets like commodities, real estate and fine art, instead of equities.

Is the 60/40 portfolio dead?

With the outlook for the U.S. economy increasingly uncertain, analysts remain divided on what comes next for the 60-40 portfolio. Dyer pointed out that if Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell follows through with a Volcker-esque shift in monetary policy to rein in inflation, it’s possible that the positive correlation between stock and bond returns could continue, as surging interest rates likely instigate further pain in bonds (which tend to sell off as interest rates rise). Such a move also could further hurt stocks (if higher borrowing costs and a slowing economy weigh on corporate profits).

Chair Powell last week reiterated that his goal of getting inflation back down to 2% and retaining a strong labor market remains a possible outcome, even though his tone on the subject has taken on a gloomier hue.

Still, there’s scope for the correlation between stocks and bonds to revert to its historical pattern. Goldman Sachs analysts warned that, should the U.S. economy slow more quickly than currently expected, then demand for bonds might perk up as investors seek out “safe haven” assets, even if stocks continue to weaken.

Bhandari said he’s optimistic that most of the pain in stocks and bonds has already passed, and that 60-40 portfolios might recover some of their losses in the second half of the year. Whatever happens next ultimately depends on whether inflation starts to wane, and if the U.S. economy enters a punishing recession or not.

Should a U.S. economic slowdown end up being more severe than investors have been pricing in, then there could be more pain ahead for equities, Bhandari said. Meanwhile, on the rates side, it has been all about inflation. If the consumer-price index, a closely watched gauge of inflation, remains stubbornly high, then the Fed might be forced to raise interest rates even more aggressively, unleashing more pain on bonds.

For what it’s worth, investors enjoyed some respite from the selling on Friday, as both bond prices and stocks rallied ahead of the holiday weekend, with markets closed on Monday. The yield on the 10-year Treasury note TMUBMUSD10Y,

The S&P 500 SPX,

On the economic data front, markets will reopen Tuesday with May’s reading on factory and core capital equipment orders. Wednesday brings jobs data and minutes from the Fed’s last policy meeting, followed by more jobs data Thursday and a few Fed speakers. But the week’s big data point likely will be Friday’s payroll report for June.