Afraid you missed the stock-market bottom? History says curb your FOMO.

Fear of missing out, or FOMO, may be helping to drive stock-market gains as major indexes rebound from 2022 lows set in mid-June — but investor angst over potentially missing the “bottom” is usually misplaced, a strategist argued in a Tuesday note.

“Many investors insist on buying early so that they ‘can be there at the bottom.’ Yet history suggests that it’s better to be late than early,” wrote Dan Suzuki, deputy chief investment officer at Richard Bernstein Advisors.

The S&P 500 SPX,

See: This stock-market milestone indicates the S&P 500 could be as much as 16% higher one year from today

The broader rally, which has seen the Nasdaq Composite COMP,

Also read: Nasdaq bull market? A history of head fakes says it’s too early to celebrate.

“Investor sentiment has gone from being very poor in June and July, with investor positioning also being light, to now talk of FOMO and a Goldilocks outcome,” said Jason Draho, head of asset allocation for the Americas at UBS Global Wealth Management, in a note earlier this week.

Draho warned that investors “becoming more optimistic in the current highly uncertain environment does make the markets more vulnerable to negative news.”

Whether mid-June marked the bottom will only be clear in hindsight. RBA’s Suzuki said an analysis of performance around past bear-market troughs shows that being fully in the market at the bottom isn’t as important as many investors might think.

Suzuki explained:

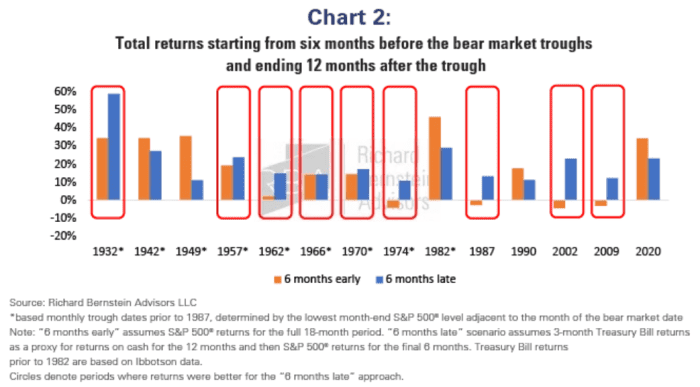

In a refresh of our previously published analysis, we analyzed the returns for the full 18-month period encompassing the six months before and the 12-months after each market bottom. We then compared the hypothetical returns of an investor who owned 100% stocks for the entire period (“6 months early”) with one who held 100% cash until six months after the market bottom, then shifted to 100% stocks (“6 months late”).

The chart below reflects the findings, which showed that in seven of the last ten bear markets, it was better to be late than early.

“Not only does this tend to improve returns while drastically reducing downside potential, but this approach also gives one more time to assess incoming fundamental data. Because if it’s not based on fundamentals, it’s just guessing,” Suzuki wrote.

What about the exceptions?

Suzuki noted that the only instances in the past 70 years where it had been better to be early occurred in 1982, 1990 and 2020. “But in each of those instances, the Fed had already been cutting interest rates,” he said. “Given the high likelihood that the Fed will continue to tighten into already slowing earnings growth, it seems premature to be significantly increasing equity exposure today.”